Good bugs, bad bugs and what to do about them in your garden, home

- Updated

Answers to your gardening questions from an expert in Southern Arizona.

- By Peter Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: I have a question regarding the attached photo of an unknown bug visiting one of my squash flower plants. This morning I counted eight of the same type crawling all over the squash flowers. Any idea of what type of bug this is and will its presence be a problem?

A: It is a striped cucumber beetle (Acalymma vittatum). They are in the family Chrysomelidae, commonly known as leaf beetles, and pests of cucurbit crops such as squash, pumpkin, zucchini, gourds, watermelon and cucumber. The adults mainly feed on pollen, flowers and foliage. The larvae feed on roots and stems.

They have the potential to spread bacterial wilt in cucurbits. I recommend removing them when you can catch them. An insect net might come in handy if you are growing a lot of these plants.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Email: plwarren@cals. arizona.edu

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: I am finding kissing bugs in my house. Is there any way to prevent them from getting in and biting us?

A: Kissing bugs (aka conenose bugs or assassin bugs) are predator insects that nest with packrats. The first step would be to reduce the packrat habitat near your home. A well-managed landscape is much less likely to harbor rodents. It is difficult to prevent insects from entering your home entirely. Kissing bugs are big enough that you can prevent entry much of the time by making sure all windows and door screens are in good repair and there are no obvious gaps.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to plwarren@cals.arizona.edu

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: I found these insects eating my potato leaves. What are they and what can I do about them?

A: The insects are called tortoise beetles because of the shape of their exoskeleton, which resembles a tortoise shell. They are plant-feeding beetles and can be an occasional pest on a variety of vegetables and weeds. The good news is the vegetable plants can handle the holes in the leaves that they make so you really don’t need to do anything to manage them. More good news is that these insects are helpful in keeping some weeds in check and have, in some cases, been raised and released to manage specific weed species.

Q: Over the course of about 5 years we have lost three 20- to 30-year-old Australian willows (we think that’s what they were) on the west side of our home. We also lost a vine on the wall surrounding the tress that has been here as long as we have, which is about 18 years. The plants in the flowerbeds around the trees such as verbena, mint and lantana also died. Irrigation has never been an issue. Our tree trimmer suggested that we might have a fungus in the earth around the trees. Coincidently, we have noticed mushrooms popping up in this area after a rain. They are the size and shape of an adult’s finger and are quite malodorous. Can you tell us how to confirm this suspicion and more importantly how to determine what is killing our plants and what we can do about it? The west side of our yard is a dead zone and I am afraid whatever is causing this is spreading.

A: Australian willows (Geijera parviflora) are evergreen trees that grow up to 25 to 30 feet tall. Branches sweep up and out and long, narrow leaves hang down giving the appearance of a weeping willow. Small white flowers are produced in the spring and fall. Because they are on the west side of your home, it would be important to screen them from western afternoon sun because their bark is susceptible to cracking from sunscald. I wonder if the other plants you mentioned were being screened by the trees that died and then they suffered a similar fate from being over exposed to the western afternoon sun. Fungi may be seen after a rain if there is any organic matter in the soil. We often see this in mulched areas or areas with trees that allows organic matter and water to mix. Your area may have built up some organic matter from the trees being there so many years. Our desert soils don’t usually have much organic matter. Without seeing the fungus in question, I suspect you are seeing what is called stinkhorn fungus. These are more common east of the Rocky Mountains but can be seen in the west. Their distinct shape, smell and orange color make them easy to spot. Fortunately, there is nothing bad to say about them except that they stink. If you don’t want to marvel at their random occurrence, you can simply rake them into the soil or dispatch them to the trash bin. I recommend planting some tougher plants that can handle the western sun on the west side of your house. If you need recommendations, please contact the Pima County Extension Office. The Master Gardener Volunteers would be glad to help.

Q: About 1 ƒ years ago I purchased four white flowering oleander plants—the tall not the petite variety. They have been deep watered regularly, fed in May and have only grown about 1/16th of an inch. They have original leaves, have flowered but have no new growth or leaves. My hope was these would grow quickly in front of my screened in porch. I have other oleanders in the back and side yards that are huge, some of which I have planted. I wonder if the soil is old as I have lived here 31 years and the home was built in 1968. There had been huge juniper trees that died over the years. Perhaps this area of soil is not rich enough to support new growth. I’ve considered moving the oleanders and putting in birds of paradise.

A: Many woody plants will take up to three years to grow a lot after planting so I think you should give it more time. Another factor could be the roots of your old junipers. If they were cut down recently and simply cut at the soil level, the stump and roots are still in the ground. That means the roots will decompose over time and in the process take nitrogen from the surrounding soil for that process, leaving less for your new plants. Not knowing the exact situation with your junipers, I am doing a little guesswork here so it would be good to have more information about the timing of their demise and the planting of your oleanders. Having your soil tested is a good idea if you are still concerned about this. There are a few labs in the area that will test it and you can call the Pima County Extension Office to ask for their contact information.

Q: I have elm leaf beetles chewing up the leaves of my Siberian elm tree. Is there an organic solution to this problem?

A: The elm leaf beetle is a serious pest of American and European elm species and less so on the Siberian elm. Since there are other pests that can cause similar shot hole damage as these beetles, it is good to be sure. The beetles are one-quarter of an inch long, olive-green with black, longitudinal stripes along the margin and center of the back. While the adult beetles chew holes through the leaves, the larvae skeletonize the leaves by feeding on the green surface tissue of the leaves. It is important to take good care of elm trees to make them able to withstand some feeding damage. A healthy tree can handle up to 40 percent defoliation, especially if this threshold is reached toward the end of the growing season. We are fortunate to have a few natural enemies that parasitize these beetles. A fly species and two wasp species are often found where these beetles thrive and as long as we can refrain from using insecticides against the beetles, these beneficial insects should do well and help keep their population under a manageable level.

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: When my car was serviced a couple of days ago a large black widow and her nest fell on the technician. He took it down and we sprayed under the car but I’m concerned there are some inside the car. Also, I’m wondering how one would be nesting under my car. My car sits in a carport and is driven almost every day. What can I do to keep this from happening again and make sure they aren’t in the car?

A: It would be good to see the nest to know if any hatched but I bet from your description that you disposed of it already. Spraying under the car may have taken care of any young ones crawling about. Mothers will stay near to defend their egg sacs and the young spiderlings stay close by her soon after they hatch. Then they go ballooning away to start their own webs in a new spot if they survive and most do not.

It is not easy to keep insects, spiders, and even rodents out of vehicles. They are excellent shelters against the environment, especially when shaded as yours is by the carport. Parking in the sun could be a benefit in this situation since it would get very hot inside and probably not be a good habitat for anything for very long.

We can sometimes screen out rodents but smaller animals are more difficult. The best way to keep them out is to make the area around your carport less hospitable so they have farther to go to seek shelter. This can be accomplished by keeping the surrounding area clear of any plant material, be they ornamental plants or weeds, and other objects that could also act as a shelter such as a woodpile or a storage shed.

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: What is this tiny black beetle with orange spots? There are a bunch of tiny black beetles with orange spots in our kitchen pantry.

A: Those are carpet beetles and their larvae you will recognize as tiny, hairy grubs. Often what are found are the cast skins of the larvae from their molts among your damaged things. They are common indoor pests of stored products and other organic materials. Back in the day, when most carpets were made of wool or other natural fibers, these insects got their name. They can be found on a variety of things besides carpets and are most likely infesting something near where you are seeing them in the pantry. These insects are sometimes used by mammalogists to clean animal skeletons in scientific collections. Sadly, they are also a serious museum pest and are notorious for eating insect collections and other dead animals. In your situation, the first things to check are any open containers of pet food, bird seed, etc. Then start working through things stored in cardboard boxes or other easily chewed containers. You might also check if you have any boxes or clothing made of natural materials. The eradication of these beetles is difficult. Sanitation and exclusion are the most important tactics.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to plwarren@cals.arizona.edu.

- By Peter Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: Yesterday evening we noticed a large number of giant mesquite beetles in a couple of branches on the seedpods obviously mating. 1. Will the females disperse to lay their eggs on other food sources? 2. Will my tree lizards eat most of the young? 3. Why the large number in one place? I consider myself quite observant and have not seen these before.

A: These insects are actually called giant mesquite bugs (Thasus neocalifornicus) and differ from beetles in that they have piercing-sucking mouthparts and front wings that overlap, among other characteristics. They are fairly common in the foothills of Tucson but not always in the same places. They are not numerous every year it seems but someone always sees them and asks about them. They are only found on mesquite trees so your other plants are safe. Since they are sap feeders and not usually found in large numbers, even the mesquite trees are safe. The young are in danger from predators but because of their warning colors (red and yellow) they have some protection. Some of them will always survive.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to tucsongardensage@gmail.com

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: Our yard backs up to the desert and every late summer for the past few years leafcutter ants raid our yard at night, stripping leaves off our banksiae rose and lantana. The have recently begun to attack a mature desert willow and it’s now almost bare. At one point the anthill was in our back yard and I used insecticide on the pile so that now they’ve moved into the desert. But they climb the fence with ease even while carrying leaves. I don’t want to spread poison in the desert but am worried our tree will not survive. (The lantanas and banksiae are hardy and always come right back). Do you have suggestions to keep the ants out?

A: Leafcutter ants are difficult to manage but one thing that slows them down is making the area less hospitable. A product called tanglefoot is a sticky substance you can spread on the base of the plants you are trying to protect and in your case maybe the wall they climb. Also diatomaceous earth is something you can spread on the ground surrounding the plants. The diatomaceous earth is abrasive and can injure the ants and the sticky stuff does just what you might think. They get stuck and can’t move much like Roach Motels that let insects check but not check out.

- By Peter Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: My question is about black widow spiders. We have been told that they are difficult to get rid of and we have had several on the outside of our home. Their web is different from most spiders so even if I see a black spider and the web is similar I kill it without checking for the red hourglass. I’m quite concerned for my grandchildren when they are here visiting, and my husband who loves to garden. First off are there black spiders that are look-alikes and should I also threat them with the same caution? What is the best way to get rid of them along with the eggs they lay? We have the outside perimeter of the house sprayed twice a year and the line of death has worked for the insects we don’t want in the house. However, walking into a spider web of any kind has me really uneasy.

A: The western black widow spider (Lactrodectus hesperus) is fairly unique in its coloration for our area so there are no lookalikes to be seen. There is a false black widow that is not venomous but it is found in southern California and other pacific coast states, primarily in urban areas as a house spider. Their color is more purplish-brown with pale yellow markings. The body of the black widow female is shiny and black and the hourglass mark on the underside is red.

The good news about black widows is that they are not aggressive and not seeking to bite humans. You are correct about them being hard to eradicate so part of being safe is teaching your grandchildren what they look like and to avoid handling them. Wearing gloves while working in the garden is always a good idea to protect against accidental encounters with black widow spiders and other things.

Perimeter pesticide sprays are not a good way to manage insects and spiders because they won’t provide long-term control. These days many pesticides degrade fairly quickly in the environment so spraying twice a year for no specific reason is basically recreational pesticide use. It is better to spot treat where and when you see insect pests so you get the best bang for your buck and so you don’t unnecessarily kill off good bugs that could be helping you manage other pests.

Reducing clutter around your home is one of the easiest ways to minimize encounters with spiders and other arthropods. Outdoors this often means keeping weeds and other vegetation under control and reducing piles of anything such as firewood or moving piles to outlying areas.

Outdoor lighting will attract insects and the spiders that eat them so you have to balance the safety of having lighting with keeping the lights from shining directly on structures. Because they are nocturnal you can hunt for spiders at night and dispatch them with your shoe or whatever tool you prefer. You can also remove them to an area away from your home if you want to be nice to them. After all, they are eating insects that might otherwise bother you so they’re not all bad.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Email: plwarren@cals. arizona.edu

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: I am writing to inquire about recommendations for a nontoxic approach to controlling citrus leafminer on a young lime tree I am growing in a large pot. I do not recall having this pest in the past and have had limes, grapefruit and lemons for many years. This new lime tree I planted about a year ago is now infested on all the new leaves and I am wondering if there might be a nontoxic method to reduce or eliminate them. I have looked up information on the web but the recommendations seem to be relatively toxic and I would prefer to avoid those if possible.

A: Because your lime tree is young, insecticides are generally recommended to prevent these insects from slowing the growth of the tree. That said, you could let your tree tough it out since there are natural enemies that prey on the citrus leafminer and the leaves they damage are still effective food producers for the tree.

Other things you can do to manage the situation include avoiding pruning except for water sprouts and branches broken by wind, et cetera, and only fertilizing outside of the normal flights of the adults. The adults are most often seen in the summer and fall months. Both pruning and fertilizing promote the new growth that is most attractive to these insects.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to tucsongardensage@gmail.com

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Question: I occasionally run across a dead branch on some of my mesquite trees. The dead branch sticks out like a sore thumb, and on closer inspection, there is a ring around the branch etched into the bark. The foliage in front of the ring is dead, but behind everything appears fine. First, do you know what causes this? Second, should I be concerned. And third, should I be preventing this and how? Right now, all I do is prune the branch out.

Answer: The ring etched in the bark is the work of the mesquite twig girdler (Oncideres rhodosticta). This beetle is in the family Cerambycidae that are commonly referred to as long-horned beetles due to their long antennae. The adults aren’t commonly seen on the trees although they are attracted to lights at night if you want to find them. The female chews a ring in the stem and deposits her eggs further out on the stem. The eggs hatch in the stem and the larvae feed on the dying wood in the stem caused by the girdle cutting off nutrients to the end of the branch. The larvae will overwinter in the wood and adults will emerge in the spring. Research has shown the damage has no affect on the health of mesquite trees and it is simply nature’s way of pruning. So the good news is you don’t have to do anything to prevent these beetles from chewing on your trees.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to tucsongardensage@gmail.com

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Question: I found this insect on my gas grill today. Is this the kissing bug I have been reading about?

Answer: What you are seeing is the giant agave bug (Acanthocephala thomasi). Kissing bugs (Triatoma species) are smaller and don’t have the bright orange feet and orange tips on the antennae. Also, the kissing bugs feed primarily on mammals, such as pack rats and humans, whereas the bug you found feeds on plants. Recently, there was a flurry of news reports in other parts of the country on the kissing bugs and the associated Chagas disease they can transmit. These stories then spread through social media, gathering some misinformation as they went. So I understand why you are concerned. Despite the media hype, this was not actually new information.

Kissing bugs are more common in the Southwest. However, the risk of Chagas disease transmission in Arizona is very low, according to University of Arizona Cooperative Extension Specialist Dawn Gouge. UA researchers found a high rate of infection (about 40 percent) of kissing bugs in southern Arizona by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi that causes the Chagas disease infection. However, the kissing bugs in Arizona differ from those in areas where Chagas disease is a health problem and are not as effective in transmitting the disease to humans. The reason has to do with the timing of blood feeding and defecating. Our local species fly then poop as opposed to poop then fly. The protozoa are passed in feces, not during blood feeding, so by waiting to defecate until after they fly from where they eat, their behavior greatly reduces chances for transmission.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to tucsongardensage@gmail.com

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: I’ve never seen a bug like this one found in my garage. It had eyes and would move quickly when I put my finger in front of it.

A: This is a solpugid. It is a member of the arachnid class in the phylum of arthropods and related to spiders and scorpions but distinct enough to warrant their own order. Their habitat is the desert and they are predators of other arthropods and have a reputation for being fast; their top speed is reportedly around 10mph. They have no venom, are harmless to humans, and do a good bit of pest management for us while we sleep. All things considered, they are good to have around.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to tucsongardensage@gmail.com

- By Peter Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: I have lived in this house since it was built in 1978 and had never seen a scorpion. About three years ago, there was a major road construction project a half mile away and that’s when the scorpions started. They began showing up about once every two to three weeks. My regular exterminator comes in March, June and September and in addition to spraying inside and out, he began laying down scorpion granules at every visit. The scorpion visits became farther apart but have continued. I was just beginning to think they had finally disappeared until this last week when I saw one crawling around my desk where I work all day, every day. He missed my wrath that day but I saw him the next day in the bathroom (I’m fairly certain it was the same one). I dispatched him immediately. Why do these nasty critters keep showing up and how can I get rid of them once and for all? My house is clear of clutter inside and out and the weeds are kept at bay.

A: You may have answered your first question already. It could be that habitat destruction from the nearby road project may have played a role in diverting the scorpion population in your general direction. How you get rid of them requires an integrated pest management approach. Pest-proofing your home is an essential first step. You’re already on the right track by keeping the area surrounding your house free of weeds. Other things that allow them refuge are stacks of anything including woodpiles, stones, bricks, etc. Install weather-stripping around loose fitting doors and windows and ensure door sweeps are tight fitting. Store garbage containers in a frame that allows them to rest above ground level. Plug holes in brick veneer with steel wool, pieces of nylon scouring pad or small squares of screen wire. Caulk around roof eaves, pipes and any other cracks into the building. Keep window screens in good repair. Make sure they fit tightly in the window frame.

Scorpions are almost impossible to manage with insecticides alone. Because they are nocturnal, spraying in the daytime is ineffective. A proactive approach is to find them before they enter your house. Scorpions fluoresce or glow under ultraviolet light so they are easy to find with the aid of a black-light during the night. Nighttime scorpion hunting is a lot of fun but make sure that you wear boots and have long tongs if you want to capture the scorpions to move them. Black-lights can be ordered from the internet or obtained from pet stores and electronic retailers. Once located, collect the scorpions using long forceps and keep them in a sealable, sturdy container. As these wonderful creatures are such a benefit to our environment please consider collecting and releasing the scorpions into the natural desert rather than killing them.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Email: plwarren@cals. arizona.edu

- By Peter L Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: Now this is a bug! What the hell is it? Eerily beautiful and frightful at the same time.

A: What you have is a whip scorpion. The only whip scorpion found in the United States is the giant whip scorpion, Mastigoproctus giganteus. The giant whip scorpion is also commonly known as the vinegaroon. To encounter a giant whip scorpion for the first time can be an alarming experience so I understand your fright. What seems like a monster at first glance is really a harmless creature.

Whip scorpions are found in the southeastern oak zone of Arizona east across the southern U.S. to Florida. They have a substantial but flat body 2-3 inches in length, with large spined, arm-like pedipalps in front. They are arachnids but have no venom. Whip scorpions are predators, active at night. The whip-like tail is used in defense and individuals can squirt acetic acid (vinegar) produced from a gland in the rear, hence their nickname: vinegaroon.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to plwarren@cals.arizona.edu

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: I was at the garden this morning and noticed how droopy our patch of sunflowers is! So I took a closer look and discovered that the leaves are infested with insects! There are little white aphid looking things, and then massive sections of black dot-looking bugs, especially underneath the leaves. Maybe you can tell from the photos I’ve attached. I did my best to give them a sudsing with Dawn. Do you think this is the remedy for these bugs? Any other thoughts?

A: The insects on your sunflowers are called lace bugs, not to be confused with lacewings, which are beneficial predators. The black spots are likely a combination of young lace bugs, which are that color, and their poop.

Lace bugs are of the true bug order we call Hemiptera and they have piercing-sucking mouthparts just like the aphids. So they suck out the sap rather than chewing the foliage. The result of large numbers of these lace bugs feeding over a period of weeks is discoloration and the droopy look you noticed.

Fortunately, they don’t damage the flowers as much as the leaves. Insecticidal soap is a good solution as is a blast from a hose. Some dish soaps are toxic to plants so if you don’t want to spend a bit more for actual insecticidal soap, you might try spraying only part of your plant to begin just in case. These insects tend to be on the underside of the leaves at least as much as we see them on the tops so make sure you spray the plants in such a way as to cover the underside of the leaves.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to plwarren@cals.arizona.edu

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: I’ve been noticing the sycamore trees around where I live look pretty awful. The leaves are pale and curled up. What is causing this problem?

A: The local trees in Tucson are being eaten by the sycamore lace bug (Corythucha ciliata), a native insect, and present across North America. Sycamore lace bugs cause damage to leaves on sycamores as well as London plane trees. These lace bugs are white in color, about 1/8 inch in size, and feed on the underside of leaves on host trees. Adult lace bugs tend to have an almost see-through appearance, which, combined with venation on wings and ridges on their bodies, lends them their common name. The nymphs differ in appearance from the adults in that they are black and spiny. Adults are very mobile and their movement is aided by wind. Lace bugs go through five life stages: egg, three immature or nymph stages, and adult. Adults overwinter in bark crevices or branch junctures, and become active again in the spring when leaves begin to break from their buds. Shortly thereafter, the adults lay eggs on the underside of leaves and eggs hatch within a matter of days of being laid. Nymphs feed on the underside of the leaves as they grow. Nymphs, which are wingless, smaller, and more rounded in shape, tend to cluster together on the underside of infested leaves. Wherever they are feeding, frass (insect feces) may be seen as well. The frass appears as tiny drops, shiny and dark in color. The life cycle is about 45 days in length, allowing for several generations throughout the year.

Early infestations are evident when white spotting begins to occur on leaves where the insects are feeding. Black spots, the frass of the insects, appear widely across the underside of the leaves as well. Heavy infestations can result in bronzing and drying of leaves. Eventually, those leaves will fall prematurely, making trees look to be in poor health. Established trees can sustain this damage for several seasons. Young or newly planted trees experience more adverse effects during infestations than established trees. The damage is more severe as weather patterns bring drier conditions.

Though there are insecticides and other types of management actions that can be taken, most damage is aesthetic. Watering trees properly can help relieve stress on trees. Additionally, strong streams of water on leaves can be effective in removing insects, especially when targeting lace bugs in the nymph stage, before severe damage occurs. However, these infestations do not require any treatment. There are also natural fungi as well as predators and parasites of lace bugs that can help manage populations.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to plwarren@cals.arizona.edu.

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: What are these little gray buggers on my sunflower leaves?

A: They are lace bugs, small plant bugs that suck plant sap from the leaves. They are often found on the underside of leaves. The grayish ones are the adults and the smaller, blackish ones are the nymphs. The smallest black spots are their frass (poop). On sunflowers, we just let them be because they might damage the leaves but the flowers are unaffected and the plants seem to tolerate them to some extent. Other plants are not as tolerant. If you wanted an organic solution you could try insecticidal soap, horticultural oil, or a pyrethroid such as PyGanic.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to plwarren@cals.arizona.edu

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Question: I’m sorry to bug you again, but I can’t think of anyone else to ask. When I have been going out in the backyard, in the dirt there are dozens of tiny craters. They are perfect, about an inch deep, and inch wide, and perfectly circular. Something is making them in the night, what can it be?

Answer: The craters are like tiny pitfall traps and each contains a doodlebug at the bottom under the sand. They are supposedly called doodlebugs because of the way they doodle in the sand while they meander about. They are young antlions, a kind of predatory insect of the family Myrmeleontidae. If you know your ancient Greek, the translation is easy (myrme = ant, leon = lion). They sit in the bottom of the cone shaped hole waiting for unsuspecting ants to fall in and then they eat them. Interestingly, these insects make their cone shaped traps using the steepest angle the sand can maintain that shape so that the slightest disturbance will cause the prey and the sand to fall to the bottom where the antlion waits, jaws up, for supper. It can be cheap entertainment for kids if they like to manually put ants into the holes and watch the carnage. That’s what we did. Caution: playing with insects is habit forming and they might grow to be entomologists like me.

Q: I am concerned about an evergreen tree in our pool area. I don’t know what it is called. It has a whorl of glossy green leaves on each branch and small flowers that smell like orange. The base is about 5 feet from the pool deck. We are concerned about roots growing and breaking through. Can you advise?

A: It is called Pittosporum tobira or Japanese mock orange. It is a slow growing shrub that requires weekly irrigation, does well in moderate sun or light shade, and grows to be 6 to 8 feet tall on average. It is a common plant around Tucson as well as Japan. It should not be a problem for your pool.

Q: We received a lovely Ficus benjamina in April. Of course, when we brought it home it dropped many leaves. Just as that was almost over some of the leaves quickly turned brown, staying on the stems, on one side. There are no signs of insects or spots on the leaves. The first couple of weeks it probably did not get enough water, we were told every two weeks. Then after searching on the web we discovered it needs watering when the surface is dry, about weekly or less in Tucson. It has been watered weekly for three weeks now. It gets sprayed daily. Both water and spray contain small amounts of Miracle-Gro indoor plant food, not the recommended amount. The brown leaves/branches are spreading to the rest of the plant. It is not dropping many leaves now. Should the branches with dead leaves be cut back?

A: The leaf drop is an indicator of stress and could be related to the environment: water, light, and temperature. The leaf browning may be a function of salt burn from excess built up in soil in your container. Repotting with fresh soil or a good soaking with high quality water should help remove or wash the salt through the soil. Then you can resume watering to keep the soil moist as you were. It’s also a good idea to put it outside in the sun if you can. Ficus trees need more light than a lot of other “house plants.”

Q: What are these little gray buggers on my sunflower leaves?

A: They are lace bugs, small plant bugs that suck plant sap from the leaves. They are often found on the underside of leaves. The grayish ones are the adults and the smaller, blackish ones are the nymphs. The smallest black spots are their frass (poop). On sunflowers, we just let them be because they might damage the leaves but the flowers are unaffected and the plants seem to tolerate them to some extent. Other plants are not as tolerant. If you wanted an organic solution you could try insecticidal soap, horticultural oil, or a pyrethroid such as PyGanic.

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: Why are bees in my vegetable garden? They appear to be digging in the soil. Makes it impossible to get veggies.

A: Many species of solitary bees make their homes in the soil. A group called digger bees or Anthophora (meaning “flower bearer”) are extremely common and they sometimes nest in large numbers like a community of single-family homes. Your garden is likely a good spot, according to the bees. They are not typically aggressive should you want to work around them. If you want to discourage them from nesting there, one thing you can try is using an overhead sprinkler in the area where they are nesting. Digger bees will often seek a new habitat if there is regular water raining down on their holes. Since these are also some of our native pollinators, it is good to keep them alive and nearby, if not in your garden.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to tucsongardensage@gmail.com

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

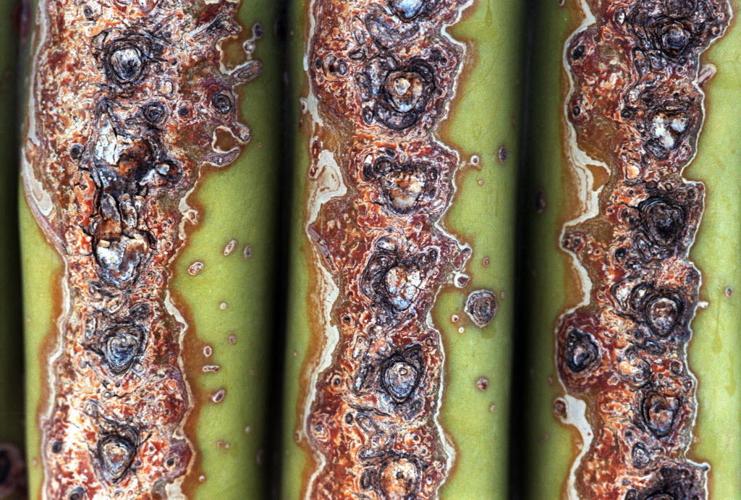

Q: We have infested-with-mealybugs prickly pears on a border with a neighbor who insists that the only way to control the infestation is to use a Bayer Tree and Shrub chemical. I so dislike and try to avoid these solutions. Can you direct me to an online intelligent discussion that isn’t sponsored by Bayer? Or do you have a nonpoisonous alternative?

A: I suspect what you are seeing isn’t mealybugs but rather Cochineal scale (Dactylopious coccus) on your prickly pear cactus. The easiest treatment is spraying them with a hose. You can also use a soap solution (1 tablespoon per gallon of water).

While the Bayer product will kill these insects, it is also likely to kill beneficial insects in the area that may be feeding on the scale insects. You and your neighbor shouldn’t expect to eradicate these insects. They are very common in our area and will likely continue to feed on the cactus no matter what method you choose.

Fortunately, they aren’t likely to kill these plants if you spray them with a hose periodically.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to

- By Peter Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: I have prickly pear cactus that has white patches on the pads that looks like little bits of cotton. What is this, and is this bad for the plant?

A: Most likely what you are seeing on your cactus is an insect called cochineal scale. These insects cover themselves with a waxy coat that appears like white, cottony tufts. To verify this is what you have, you can crush one of them to see if it leaves a bright, red stain. This red material is the blood of the insect, and its color is due to the presence of carminic acid. Humans use this to produce carmine dye for various things including food coloring and lipstick.

Scale insects insert their mouth parts into the cactus to feed on the sap, and over time can reduce the vigor of the plant. You can help your cactus by spraying the insects with a hose periodically and/or using insecticidal soap.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: What are these bugs on this milkweed?

A: The red and black ones are milkweed bugs. That might seem like a snarky answer but it’s the official common name for these insects otherwise known as Oncopeltus fasciatus. They can also be found on oleander plants, which might explain why the yellow insects are called oleander aphids (Aphis nerii).

Both species are commonly found on milkweed and oleander plants. Insects tend to favor specific plants or plant families when they feed. Milkweed and oleander are relatives from the same plant family and known for their sap that contains cardiac glycosides, which are poisonous. The insects that ingest it as a food source are able to sequester it and become protected to some extent.

If you watch other animals preying on these insects, you may notice they spit them back out. The red and yellow coloration is nature’s way of warning predators to leave them alone but not everyone understands the warning signs without a taste test.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: These caterpillar bugs are all over my Texas mountain laurel (the same one that had the red and black plant bugs in March – which I sprayed off with a soap solution). There are probably at least 10 groups of these caterpillars on the tree. Suggestions?

A: These insects are called genista caterpillars (Uresiphita reversalis) and they are commonly found throughout the southwest on Texas mountain laurels. Their damage doesn’t affect the overall health of the tree unless there are unusually high numbers of them. The damage is often only cosmetic. The same soap solution can be used against these caterpillars. Soap acts an irritant and doesn’t always completely solve the problem. You might get the same result by spraying them with a hose. The benefit of the caterpillars is they are food for birds so you could leave them there and put up with the minor damage the caterpillars cause when feeding. Other solutions include pruning off the infested ends of branches, hand-picking the caterpillars, and various insecticides labeled for use on landscape trees and shrubs. An organic solution is spraying Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) on the leaves where they are feeding. This works best when the caterpillars are young and most susceptible to the poison. The Bt bacteria are poisonous to caterpillars but not to anything else. Since there are several strains of Bt, make sure you use the one labeled for caterpillar pests. As always, when using any pesticide it is important to read the label and follow instructions to protect you and those other non-target organisms that might be exposed to the spray. By the way, the red and black bugs (Lopidea major) you saw earlier this year are also just a minor pest that feeds on Texas mountain laurel.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed totucsongardensage@gmail.com

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: I live in Sierra Vista and have a small peach tree, about 3 to 4 years old. Last spring it bloomed for the first time and set about a dozen peaches. When the fruit was a bit smaller than golf ball size, I noticed each one had a small hole and was oozing a clear sap-like substance. I assume an insect of some kind that had bored into the fruit caused it. Each peach shriveled up and fell off the tree. With what should I treat my tree and when to prevent this again?

A: Peaches and other fruits such as pomegranates are potential food for a few different insect species. Based on your description, I suspect one of the larger plant bugs we refer to as leaf-footed bugs. They have piercing-sucking mouthparts that penetrate the fruit to suck out the sap. Their saliva has a toxin in it that injures the fruit. The resulting wound is also an entry point for disease and that is possibly what caused the fruit to shrivel and fall from the tree. Treating for this insect is challenging because as adults they are fast moving and can fly. The insecticides used are contact poisons so you need to know where they are and hit them directly with the treatment. There are organic and conventional insecticides available for this pest.

The best time to treat for them is when they are young. The young are yellow-orange in color and usually hang out in a group. Since you have a small tree this will be easier than if you had an orchard of trees to monitor.

The other thing you can do is look for eggs on your tree and remove them before they hatch. This hatch occurs in a week or less after they are laid so monitoring once a week is critical to removing them before they emerge. The eggs are laid in a row along a stem or the midrib of a leaf and are golden-brown in color. Since these insects also feed on citrus and pomegranates, it is good to monitor those plants as well if you have them nearby.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to

- By Peter L. Warren Special to Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: My tomatillos are full of holes and I can’t figure out what happened. What should I do to prevent this next time?

A: The culprit that damaged your tomatillos is the tomato fruitworm (Heliothis zea) aka the corn earworm. This is a common pest of these plants across the U.S.

Spinosad (many brands) works well on moth larvae like the tomato fruitworm, but it does nothing once larvae are already within the fruit. In your case, they are already finished and moved on to pupate in the soil. If you start seeing fruitworms in tomatoes or tomatillos, start applying spinosad every five to seven days through harvest. Focus on fruits higher up and on the outside of the plant where females prefer to lay eggs. Spinosad may be applied up to one day before harvest. Since your tomatillos are already affected, make note of when you started seeing the damage so you can be prepared a few weeks in advance for the next crop.

If you have any corn still in the silking stage, you can prevent corn earworm larvae from entering the corn by spraying (or rubbing) the silk with one part Bacillus thuringiensis (many brands) to 20 parts pure oil (mineral, corn, or soybean). Start this treatment when pollination is almost complete, which is when the silk tips have begun to wilt and turn brown.

Q: I planted a Bearss Lime tree about five years ago. When we had the bad freeze a few years ago it froze. Since then it has come back and has grown very well. However it never produces. I fertilized this year. It had blossoms but no limes. Can you suggest a remedy? I also water it regularly.

A: It seems you have the basic care strategy down but maybe it could be tweaked to be more effective. To start, we recommend fertilizing citrus three times per year: January/February, April/May and August/September. The amount of fertilizer you use should be based on the type, age and size of the tree. We have a chart you can use by searching for “University Arizona citrus fertilizer” on the Internet.

Watering should be done every seven to 10 days to a depth of 36 inches in the summer. In the spring and fall you can back off to watering every 10 to 14 days and in the winter, water every 14 to 21 days. This is for citrus planted in the ground. If your tree is in a container, you will have to water more often and base that frequency on how fast the soil dries out.

Bees and the wind will accomplish most of the pollination of citrus flowers. If you are not seeing any bees on your citrus flowers that could be a problem. Making sure you have an attractive habitat for bees by planting other flowering plants nearby is helpful as is providing a water source. Also keep in mind that citrus produce more blossoms than fruit.

Q: I have two mature olive trees in my back yard. They do not fruit. I would like to know how much to water them especially now in the hot Tucson summer. Also both have sprouted suckers and I am not sure how or when to prune these.

A: Olive trees need water every seven to 14 days to a depth of 24 to 36 inches during the summer. In the spring and fall you can back off to every 10 to 21 days and in the winter every 14 to 21 days.

You can prune suckers any time. The way you prune them is close to the branch they are growing from without leaving a large stub or going too close to the branch so as to make a cut flush with the branch surface. There is a nice publication at the UA that provides illustrations of these cuts. You can search for it by using the publication number AZ1499. If the suckers are coming from under ground, prune at the ground level.

Q: I am having a problem with my almonds and have had the same problem for the past couple of years. I believe it starts with a leaf-legged bug that causes the fruit to secret sap, and within days the punctured area has this hole where the almond has been removed. Can you help me find what kind of pest is causing this and how to get rid of it? The tree has gone from producing bags of almonds to just 12 total last year.

A: I agree with your diagnosis. The leaf-footed bug is a pest of almonds, pecans, pomegranates, and citrus, among others. They damage the fruit by feeding on it with their piercing-sucking mouthparts. While we may see them feeding, often what we find are the results after the fruit shows signs of rot from the feeding site. There are synthetic insecticides such as Sevin that can be used or if you prefer an organic solution there are pyrethroids such as PyGanic that are OMRI registered products that offer the same result. In either case, it is important to target the insects with the spray since they are contact poisons. The young bugs are the most susceptible and the easiest to target so it is a good idea to monitor your plants every week or so in the spring.

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: When your time permits, Would you share your thoughts on this newest visitor to the garden? He/she has increased in numbers over the past weeks and I have yet to determine which plant is part of their meal choices.

A: The insect, Pyropyga nigricans, is a firefly species without a light. These are predatory insects and are garden helpers so you’re lucky to have them.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: This year, we have some peaches with dimples. The fruit is rotten inside. Could it be a plant pathogen of some kind?

A: The short answer is yes. Your peaches are likely suffering from a pathogen as a result of insect feeding damage. The prime suspect in this case is the leaf-footed bug. These insects have piercing-sucking mouthparts and while feeding on young developing fruit leave scars that are known as cat-facing and sometimes this feeding activity will introduce fungi that may cause the rot.

Leaf-footed bugs are common in our area and may feed on a variety of plants including pomegranate, pecan, citrus, and peaches. They are difficult to manage once in the adult stage because they can fly and move about quickly.

There are insecticides available, but they are only effective on the young bugs. These insecticides are harmful to bees, so take care to avoid spraying plants in bloom. Monitoring for and removing egg masses in the early spring is another tactic that is potentially more successful if you are persistently looking in the spring when eggs are laid and young bugs are emerging from them.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to tucsongardensage@gmail.com

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: I have a question related to the “Desert Museum” palo verde.

I want to plant this tree at our house, but I am a little wary because of the threat of palo verde beetles getting to the roots and killing it prematurely. Perhaps you can help me assess this risk?

A: The main risk for these beetles is an unhealthy tree. The palo verde beetle is endemic to this area and there is little to be done to a tree that has been infested. They are known to attack stressed trees so the best prevention is to keep trees as healthy as possible. This is primarily accomplished by providing proper irrigation and pruning. Since these are native desert trees they can survive on rainwater but when we have drier conditions than usual, supplemental water can help. Typically for desert trees this means installing drip irrigation around the tree at the drip line and providing deep watering to a depth of 24 to 36 inches every 14 to 21 days in the spring, summer, and fall. In the winter you can skip the irrigation, assuming we have normal winter rains. Proper pruning when the tree is young will result in a mature tree that is structurally stronger, lives longer, and is less costly to maintain. Don’t be in a hurry to prune at planting. A newly planted young tree should be given a chance to put down roots before taking any branches off unless they were damaged in the planting process. After a year or so it will be time to structurally prune your tree to ensure its long-term health.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to tucsongardensage@gmail.com

- By Peter Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: The bark of my palo verde tree had yellow-orange blotches on it about six inches in length just about everywhere. I noticed that there is a hole in what looks to be the center of each of these blotches. It looks as though something has either bored into or out of the tree. The bore diameter is around 1/16th of an inch.

1. Is there any chance of salvaging the tree?

2. I have another palo verde around 10 feet from the effected one that shares the same canopy. Is the second palo verde at risk? If so, what can I do to minimize contamination?

3. The trees are in the same wash are the same age and share a microclimate. Are there any reasons why one was affected?

4. Is there anything I can do to ensure that if I do lose the one tree I will not lose any more?

A: The beetles were identified by Gene Hall of the University of Arizona Entomology Department as Trogoxylon prostomoides, a type of wood-boring beetle found in a variety of dead and dying trees. They are not the cause of death, but rather a decomposer species that is attracted to the tree by way of chemical cues the tree gives off as it dies.

There is nothing to do to manage the beetles because they are endemic to the area. However, you can manage the health of nearby trees to make them less susceptible to attack. This mainly includes sufficient watering for desert species such as palo verde trees. Desert trees need a good soak every two to three weeks during the spring, summer, and fall to a depth of 24 to 36 inches.

These beetles have been found in other desert legume species in the plant family Fabaceae such as mesquite. This family includes many native Sonoran Desert trees and they are all known for their drought tolerance but long-term drought conditions can be hard on even the toughest plants.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Email: plwarren@cals. arizona.edu

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: I see these red bugs on the new growth of my Texas mountain laurel. It did not bloom last year and it was suggested that I am not watering enough. So I have been and now I have these guys. I don’t know if you can see in the picture but there is clear sap all around as well. I am thinking these are not beneficial? What should I do? They appear to be doing a lot of damage to new growth, so I am going to use a soap mixture to deal with them.

A: These red bugs (Lopidea major), also known as the sophora plant bug or mountain laurel bug, are relatively harmless although not beneficial. They will suck some sap and do minor aesthetic damage to the new growth for a short time in the spring. They will not do enough damage to justify spending time and money managing them. Insecticidal soap is a good solution as an irritant for small soft-bodied insects and may disrupt their feeding activity. If your soap solution doesn't work as you hope and you are determined to manage them, you might try an organic pyrethroid product called Pyganic that is more effective against plant bugs of this order.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to tucsongardensage@gmail.com

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: My grape arbors are full of these bugs — hundreds of them eating my figs and grapes. I’ve never seen anything like this before. I shake the grape arbors and swarms fly out. Is there something we can do? Help! Attack of the June bugs!

A: They are sometimes called June bugs based on the time of year we see them. Today they are called March bugs. They are also called fig beetles (Cotinis mutabilis) and their white grubs are often found in the soil as people prepare their garden beds for planting. As adults, they can be managed with conventional insecticides, assuming this is not an organic operation. There are a variety of insecticides that work well and are labeled for use on grapes and figs. The problem is the beetles can fly and when there are large numbers of them it requires repeat treatments. So you can’t really stop them, you can only hope to contain them. There aren’t any great organic solutions for the adults unless you count the two brick method. Insecticides should not be sprayed while plants are blooming to conserve our valuable pollinators.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to tucsongardensage@gmail.com.

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: Yesterday I found two bees entering my single-story home's rafters through two small openings in the stucco and wood. Also, the bees tracked towards me after I stood nearby. Then, this evening, I found a 20-inch long and two-inch wide dark spot in my ceiling. This spot is directly below the two spots where I saw the bees entering the rafters. However, I don't hear any buzzing. Also, I went into my attic area, but couldn't see the floor due to the insulation in the attic. What actions would you recommend I take?

A: If you see honeybees coming and going from a hole in your home on a regular basis, there might be a colony living inside. The sign on your ceiling makes it more suspicious and if related could mean the bees have been there for a while. If you continue to see bees coming and going from that area, I recommend you have a professional take a closer look. This is a job for beekeeper or a pesticide control operator. You don't want a bunch of bees coming after you in defense of their colony. Depending on where you live, there is likely a list of people who will inspect this situation and do any remedial work for you for a fee. If you live in Tucson, a list can be found on the Tucson Beekeepers Facebook page.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to tucsongardensage@gmail.com

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: I have attached a photo of my coral aloe (Aloe striata). After much searching, I believe the hideous, growth seen in the photo is aloe cancer/gall/mite? I have dug up, bagged and put the plant in the trash. Apparently, I can never have another aloe again except Blue Elf? Is this true, and is this wretched little mite a menace to my neighbor’s aloes? Is there anything else I should do? It makes me almost miss the killing freezes in Colorado!

A: I believe you are correct about the diagnosis. That appears to be damage caused by the eriophyid mite (Aceria aloinis). Because these mites are microscopic, it is difficult to know they are there until the damage is seen. There is some anecdotal evidence that the “Blue Elf” variety of aloe is unaffected but there is no science to back this up that I have seen. On the other hand, other known host plants include the aloe species arborescens, dichotoma, nobilis, and spinossima as well as Haworthia species. In general, I don’t see these mites as a widespread problem so I wouldn’t put all my aloe investments in one species. They are sporadic pests on aloes and based on the number of questions I get, many people don’t have a problem with them. These mites can spread by crawling and by wind. Because they can’t fly it isn’t a quickly spreading problem and your neighbor’s plants could very well be safe from infestation. What you did by bagging the infested plant and disposing of it is the best thing to do and probably enough to stop it from spreading.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to

- By Peter Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: What do mites look like?

Answer: There are different kinds of mites. They are all related to spiders, ticks, and scorpions and they are members of the Arachnid class of Arthropods. The most common ones we see on plants are spider mites and resemble tiny spiders under magnification. Another type of mite that may be found on plants is called the eriophyid mite. These look more like maggots and are generally much smaller so you would probably need a microscope to see them. They sometimes cause plant galls to form where they feed. While some mites are plant feeders, some feed on mold, and dust mites feed on dead skin. Other mites are predators and parasites that feed on insects such as honey bees, animals such as birds and bats, or in the case of chiggers, animals like us. As the song goes, “Well little bugs have littler bugs upon their backs to bite ’em. And the littler bugs have still littler bugs and so ad infinitum.”

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Email: plwarren@cals. arizona.edu

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: Any idea whose eggs these are? They were on an orange tree in Tucson.

A: Katydid laid those eggs. Technically, katydids are grasshoppers of the long-horned variety (Family Tettigoniidae) due to their long antennae. They get their name from the noise they make in the evenings that seems to say ka-ty-did if you use your imagination. Because they often resemble the leaves of trees they inhabit, it is difficult to see them unless they move about. Their eggs resemble small seeds and are laid in a nice row on foliage or stems mostly. Like other grasshoppers, katydids feed on foliage although no appreciable damage is done so they are more of a curiosity than a pest.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to tucsongardensage@gmail.com

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: We have been having a bad stink bug infestation (hemipterans not pinacate beetles) the past couple of years in the garden. This past year they were out early and often and basically ruined the entire tomato crop. We are at 5,000 feet and don’t plant until May. First fruits are almost never harvested before Aug. 15. It is a cold zone with 46 nights at or below freezing so far this winter (no that is not a misprint). Do you have any suggestions to deal with these pests?

A: There are a couple things you can do. First, it is helpful to scout once a week when your crop comes up to see when the stink bugs begin to lay eggs. They are laid in a mass of 10-25 on the underside of leaves and look like tiny barrels. You can reduce the population significantly by removing the eggs before they hatch. Once they hatch and are actively feeding you can spray them and the sooner, the better while they are still young. If your crop is organic there is a product called PyGanic that works pretty well on hemipterans. If you use conventional pesticides, there are more choices but they may have some restrictions on when you apply them relative to when you harvest.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to tucsongardensage@gmail.com

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: I’m concerned about the recent news stories about new diseases such as the Zika virus spread by mosquitoes. I spend a good amount of time outdoors gardening and mosquitoes usually bite me. Are there any things I can do to prevent this problem?

A: Zika virus is transmitted to people primarily through the bite of an infected Aedes mosquito. These are the same mosquitoes that spread dengue and chikungunya viruses. Aedes mosquitoes prefer to live near people and only female mosquitoes bite. They are mostly daytime biters, but can also bite at night. Mosquitoes acquire the virus when they feed on a person during the first week of infection when they are carrying high numbers of Zika virus in their blood. Once inside the mosquito, the virus moves from the digestive tract into the salivary glands, a process which is thought to take about a week. After that time, the mosquito can spread Zika to the next person she bites. Zika virus can also be transmitted from mother to her fetus during pregnancy, through blood transfusions, and through sexual contact.

The best way to avoid getting Zika virus or other diseases spread by mosquitoes is to avoid being bitten by infected mosquitoes. We can minimize mosquito numbers by eliminating breeding habitats, for example, standing water in containers around our homes. When outdoors, dress properly and apply insect repellent. Here is a link to a publication on choosing repellents: extension.arizona.edu/sites/extension.arizona.edu/files/pubs/az1311.pdf

Other things you can do include the following.

• Switch to LED lights to be used outdoors - these are not attractive to mosquitoes because they have no ultraviolet spectrum.

• Place fine mesh over rain barrels to prevent egg laying.

• Repair screens for windows that may have developed holes.

• Repair leaky pipes and faucets.

• Mosquito dunks for ponds, birdbaths, and other water features with standing water.

What doesn't work - electronic bug zappers and high frequency repellent devices.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to tucsongardensage@gmail.com

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Q: I have been buying firewood (mesquite and eucalyptus) to burn some and use some for woodcrafts like lathe-turned vases. It is common for the wood to be full of large round and oblong holes that are caused by some type of insect. Recently I was able to extract two almost whole grubs of some sort from a piece of mesquite. One “grub” is essentially round, and the other has a large head, sort of triangular, and a smaller round body. Can you tell me what these are and if they pose any danger to my house? Is there anything I can do to get rid of them?

Also, I cut some fresh mesquite last spring and left it in my garage to dry over the summer. It became riddled with small circular holes, apparently caused by some different insect. In this case the damage is pretty much limited to the early, or sap wood. Can you also give me some information about the insect that causes this other type of damage?

A: The two grubs are representatives of common wood-boring beetles from the Buprestidae and Cerambycidae families of insects. The round one is a larva of a long-horned beetle and the one with the large head is a larva of a metallic wood-boring beetle. Both of these insects are associated with dying or dead trees. Their galleries can be seen on sapwood, as you described, and the adult beetles are commonly seen emerging from firewood. They are not known to infest or reinfest dry wood so your home is safe. The small circular holes are from bark beetles, another species commonly associated with dying and dead trees in our area. In the forest, these three are examples of insects helping decompose trees into soil. Without them and the associated fungi and bacteria, we would be up to our eyeballs in timber and our soils would have even less organic matter than usual.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Email him at csongardensage@gmail.com

- By Peter Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

Q: I have a question regarding the attached photo of an unknown bug visiting one of my squash flower plants. This morning I counted eight of the same type crawling all over the squash flowers. Any idea of what type of bug this is and will its presence be a problem?

A: It is a striped cucumber beetle (Acalymma vittatum). They are in the family Chrysomelidae, commonly known as leaf beetles, and pests of cucurbit crops such as squash, pumpkin, zucchini, gourds, watermelon and cucumber. The adults mainly feed on pollen, flowers and foliage. The larvae feed on roots and stems.

They have the potential to spread bacterial wilt in cucurbits. I recommend removing them when you can catch them. An insect net might come in handy if you are growing a lot of these plants.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Email: plwarren@cals. arizona.edu

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

Q: I am finding kissing bugs in my house. Is there any way to prevent them from getting in and biting us?

A: Kissing bugs (aka conenose bugs or assassin bugs) are predator insects that nest with packrats. The first step would be to reduce the packrat habitat near your home. A well-managed landscape is much less likely to harbor rodents. It is difficult to prevent insects from entering your home entirely. Kissing bugs are big enough that you can prevent entry much of the time by making sure all windows and door screens are in good repair and there are no obvious gaps.

Peter L. Warren is the urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension and the University of Arizona. Questions may be emailed to plwarren@cals.arizona.edu

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

Q: I found these insects eating my potato leaves. What are they and what can I do about them?

A: The insects are called tortoise beetles because of the shape of their exoskeleton, which resembles a tortoise shell. They are plant-feeding beetles and can be an occasional pest on a variety of vegetables and weeds. The good news is the vegetable plants can handle the holes in the leaves that they make so you really don’t need to do anything to manage them. More good news is that these insects are helpful in keeping some weeds in check and have, in some cases, been raised and released to manage specific weed species.

Q: Over the course of about 5 years we have lost three 20- to 30-year-old Australian willows (we think that’s what they were) on the west side of our home. We also lost a vine on the wall surrounding the tress that has been here as long as we have, which is about 18 years. The plants in the flowerbeds around the trees such as verbena, mint and lantana also died. Irrigation has never been an issue. Our tree trimmer suggested that we might have a fungus in the earth around the trees. Coincidently, we have noticed mushrooms popping up in this area after a rain. They are the size and shape of an adult’s finger and are quite malodorous. Can you tell us how to confirm this suspicion and more importantly how to determine what is killing our plants and what we can do about it? The west side of our yard is a dead zone and I am afraid whatever is causing this is spreading.

A: Australian willows (Geijera parviflora) are evergreen trees that grow up to 25 to 30 feet tall. Branches sweep up and out and long, narrow leaves hang down giving the appearance of a weeping willow. Small white flowers are produced in the spring and fall. Because they are on the west side of your home, it would be important to screen them from western afternoon sun because their bark is susceptible to cracking from sunscald. I wonder if the other plants you mentioned were being screened by the trees that died and then they suffered a similar fate from being over exposed to the western afternoon sun. Fungi may be seen after a rain if there is any organic matter in the soil. We often see this in mulched areas or areas with trees that allows organic matter and water to mix. Your area may have built up some organic matter from the trees being there so many years. Our desert soils don’t usually have much organic matter. Without seeing the fungus in question, I suspect you are seeing what is called stinkhorn fungus. These are more common east of the Rocky Mountains but can be seen in the west. Their distinct shape, smell and orange color make them easy to spot. Fortunately, there is nothing bad to say about them except that they stink. If you don’t want to marvel at their random occurrence, you can simply rake them into the soil or dispatch them to the trash bin. I recommend planting some tougher plants that can handle the western sun on the west side of your house. If you need recommendations, please contact the Pima County Extension Office. The Master Gardener Volunteers would be glad to help.

Q: About 1 ƒ years ago I purchased four white flowering oleander plants—the tall not the petite variety. They have been deep watered regularly, fed in May and have only grown about 1/16th of an inch. They have original leaves, have flowered but have no new growth or leaves. My hope was these would grow quickly in front of my screened in porch. I have other oleanders in the back and side yards that are huge, some of which I have planted. I wonder if the soil is old as I have lived here 31 years and the home was built in 1968. There had been huge juniper trees that died over the years. Perhaps this area of soil is not rich enough to support new growth. I’ve considered moving the oleanders and putting in birds of paradise.

A: Many woody plants will take up to three years to grow a lot after planting so I think you should give it more time. Another factor could be the roots of your old junipers. If they were cut down recently and simply cut at the soil level, the stump and roots are still in the ground. That means the roots will decompose over time and in the process take nitrogen from the surrounding soil for that process, leaving less for your new plants. Not knowing the exact situation with your junipers, I am doing a little guesswork here so it would be good to have more information about the timing of their demise and the planting of your oleanders. Having your soil tested is a good idea if you are still concerned about this. There are a few labs in the area that will test it and you can call the Pima County Extension Office to ask for their contact information.

Q: I have elm leaf beetles chewing up the leaves of my Siberian elm tree. Is there an organic solution to this problem?

A: The elm leaf beetle is a serious pest of American and European elm species and less so on the Siberian elm. Since there are other pests that can cause similar shot hole damage as these beetles, it is good to be sure. The beetles are one-quarter of an inch long, olive-green with black, longitudinal stripes along the margin and center of the back. While the adult beetles chew holes through the leaves, the larvae skeletonize the leaves by feeding on the green surface tissue of the leaves. It is important to take good care of elm trees to make them able to withstand some feeding damage. A healthy tree can handle up to 40 percent defoliation, especially if this threshold is reached toward the end of the growing season. We are fortunate to have a few natural enemies that parasitize these beetles. A fly species and two wasp species are often found where these beetles thrive and as long as we can refrain from using insecticides against the beetles, these beneficial insects should do well and help keep their population under a manageable level.

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

Q: When my car was serviced a couple of days ago a large black widow and her nest fell on the technician. He took it down and we sprayed under the car but I’m concerned there are some inside the car. Also, I’m wondering how one would be nesting under my car. My car sits in a carport and is driven almost every day. What can I do to keep this from happening again and make sure they aren’t in the car?

A: It would be good to see the nest to know if any hatched but I bet from your description that you disposed of it already. Spraying under the car may have taken care of any young ones crawling about. Mothers will stay near to defend their egg sacs and the young spiderlings stay close by her soon after they hatch. Then they go ballooning away to start their own webs in a new spot if they survive and most do not.

It is not easy to keep insects, spiders, and even rodents out of vehicles. They are excellent shelters against the environment, especially when shaded as yours is by the carport. Parking in the sun could be a benefit in this situation since it would get very hot inside and probably not be a good habitat for anything for very long.

We can sometimes screen out rodents but smaller animals are more difficult. The best way to keep them out is to make the area around your carport less hospitable so they have farther to go to seek shelter. This can be accomplished by keeping the surrounding area clear of any plant material, be they ornamental plants or weeds, and other objects that could also act as a shelter such as a woodpile or a storage shed.

- By Peter L. Warren Special to the Arizona Daily Star

Q: What is this tiny black beetle with orange spots? There are a bunch of tiny black beetles with orange spots in our kitchen pantry.