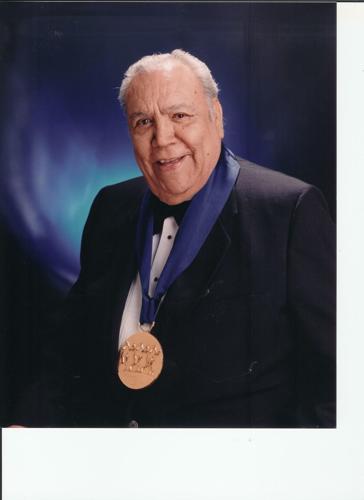

He pioneered Mexican music in the Southwest and beyond, writing hundreds of songs in multiple genres, including two time-honored classics.

His work, spread over 70 years, reflected political challenges and social changes before most musicians took up causes, inspired numerous younger musicians to break down the barriers they faced and he received the 1996 National Medal of Arts.

Eduardo “Lalo” Guerrero was an American-born champion of his Chicano/Mexican culture, which was nurtured from his upbringing in Tucson’s Viejo Barrio and professional years in Los Angeles.

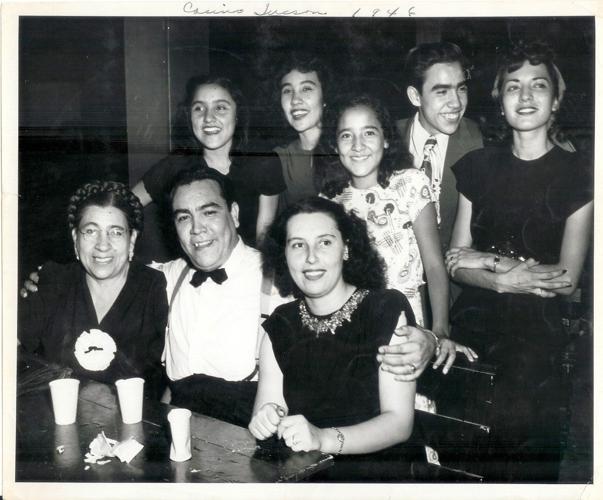

This Christmas Eve, Guerrero, who passed away in 2005, would have turned 100. Guerrero’s family, friends and fans will remember him Dec. 9 at El Casino Ballroom in South Tucson.

“Lalopalooza: Celebrating A Century Of The Father Of Chicano Music, Tucson’s Own Lalo Guerrero,” sponsored by radio station KXCI-FM, will be filled with memories and music of Guerrero featuring his sons, Dan and Mark Guerrero; singer Ersi Arvizu with guitarist Ry Cooder; Tucson ranchero singer Adalberto Gallegos; Los Angeles-based, Tucson-born jazz bassist Rene Camacho; Tucson’s Guerrero tribute band Los Nawdy Dogs; local folk musicians Ted Ramirez and Bobby Benton and the youth mariachi group, Los Changuitos Feos.

It’s the kind of Tucson party that Lalo would have appreciated.

“He was born on Christmas Eve and died on St. Patrick’s Day. Whether he was coming or going, Lalo was the party,” said documentary film maker Dan Buckley, who along with Pepe Galvez of KXCI hatched the celebration.

Buckley, a former writer with the Tucson Citizen who interviewed Lalo numerous times, calls Guerrero “one of the most important singer-songwriters of the 20th century.”

The barrio

In Guerrero’s 2002 autobiography, “Lalo: My Life and Music,” co-written with Sherilyn Meece Mentes and published by University of Arizona Press, he writes about his happy but difficult life in the barrio. His mother, Concepción, gave birth to 18 children; only 11 lived past their first year. His father, Eduardo, worked for Southern Pacific railroad and did all he could to support the family.

Lalo was born in a house at the corner of Meyer and Simpson streets in Barrio Viejo, a place he returned to often after leaving for California. His song “Barrio Viejo,” memorializes the neighborhood and later became the cornerstone for “Chávez Ravine: A Record by Ry Cooder.” It was Guerrero’s final studio recording and released shortly after he died in Rancho Mirage, Calif. He was 88.

It was Lalo’s mother, with her beautiful soprano voice, who imbued him with the love of music, and taught him to play guitar and Mexican songs.

As a child and teen, Lalo gravitated toward music. He taught himself to play the piano. He idolized singer Rudy Vallee and other popular crooners. He loved seeing westerns and musicals at the Lyric movie theater on West Congress Street. And he soaked up the sounds and rhythms he heard at the Beehive jazz and blues club in the barrio.

“When it came to music, I was like a funnel,” he wrote in his book. “I’d take everything in. I didn’t care where it came from or whether it was in English or Spanish.”

Los Carlistas

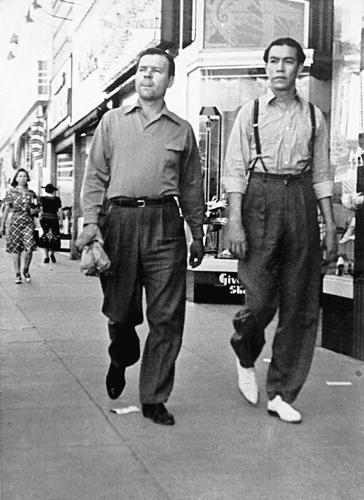

With his grasp of music and the guitar, and possessing a good singing voice, the teenage Guerrero and two barrio buddies formed a trio, performing around town. But he began to make his musical mark after joining the quartet, Los Carlistas.

Guerrero, Greg “Goyo” Escalante, and Chole and Joe “Yuca” Salaz were the toast of the barrio and Tucson. The bilingual foursome played at weddings, anniversaries, quinceañeras, and on local radio. They also appeared on the other side of the railroad tracks for English-speaking fans at the Arizona Inn, the Pioneer Hotel and El Conquistador Hotel. The group also moved to Los Angeles and played in clubs, on radio and on stage. Los Carlistas also had a bit part in a Gene Autry movie.

Years later, Lalo performed at the home of a big fan, Gilbert Ronstadt, whose Sonoran-born father was a Tucson business pioneer. A very young Linda Ronstadt would sit and listen to classic Mexican songs, and in the 1990s the music superstar would record a chart-busting mariachi record, “Canciones de mi Padre.”

Los Carlistas hit the big time in 1939 when it appeared at the World’s Fair in New York City and performed on “The Major Bowes Amateur Hour” radio program, the “American Idol” show of its time. Probably for the first time a Chicano musical group performed standard songs in Spanish and English for a country that wasn’t even aware of what a Chicano was.

Los Carlistas launched his career but it was a song that immortalized Lalo.

”Canción Mexicana”

Lalo’s Mexican-born parents and his immigrant neighbors inculcated him with a love for Mexico — its music, history and culture. His parents had fled Mexico at the start of the 1910 revolution. When Lalo was a senior at Tucson High School, his father took the family to live in Mexico City but shortly returned to Tucson at his mother’s insistence.

When Lalo was 17, even before visiting Mexico, he wrote his most enduring song, “Canción Mexicana.” In his book, Lalo wrote it was “a gift to the people of my old barrio to remind them that, even if we were poor, we had something to be proud of.”

As it turned out it was a gift to Mexico and the diaspora of Mexicans everywhere. It’s the unofficial anthem of Mexico, said Dan Guerrero, a Los Angeles stage actor and producer.

“There’s not a mariachi who doesn’t know that song,” he said.

But Lalo almost lost that song — and the much deserved recognition. Several years after writing “Canción”, he traveled to Mexico City in 1939 with the hope of selling it and three other compositions. He registered them with a publishing house but departed without a contract.

After the outbreak of World War II, Lalo was living and working in San Diego with his first wife, Margaret Marmion, of Tucson. One evening he heard the voice of the popular Lucha Reyes singing his song on the radio. He was on a train to Mexico City the next day and stormed into the publishing house asking about his song which Reyes had claimed to write. But it was his.

Years later the famed Mexican Trio Los Panchos heard a song sung by Guerrero. The trio asked to record it. “Nunca Jamás” became a huge hit and has been recorded endlessly.

The last time Guerrero publicly performed “Canción” was Oct. 9, 2004 at the Anselmo Valencia Amphitheater at Casino del Sol. It was the celebration of the 40th anniversary of Los Changuitos Feos de Tucson, the first youth mariachi group in Tucson.

Victoria Sanchez remembers. She was a 13-year-old, eighth-grade student with the Changuitos. She sang the song with Lalo, backed by Tucson’s Mariachi Cobre.

“It’s very significant to me. I took a lot of pride in the lyrics,” said Sanchez, 25, a graduate of the University of Arizona and a dancer with Ballet Folklórico Tapatío. Looking back at that night, Sanchez remains humbled.

“It was a blessing. I’ll never forget it,” she added.

Chávez Ravine

Guitarist and record producer Cooder well remembers his intersection with Lalo. His acclaimed “Chávez Ravine,” a tribute to the Mexican-American Los Angeles enclave that was razed to build the Dodgers baseball stadium and a post-World War II changing American city, would not have happened without Lalo’s participation.

Lalo had lived it in Tucson and Los Angeles, and documented the Chicano urban experience with his songs.

“It’s pretty amazing to have the kind of grasp of things he had,” said Cooder, who lives in Santa Monica. “Lalo put his knowledge to work. He wasn’t just a band leader in East LA. That is too narrow a perspective.”

In addition to “Barrio Viejo,” Cooder’s album included “Los Chucos Suaves,” one of several songs that captured the ‘40s pachuco period, a time when young Chicanos expressed their growing cultural identity and independence in their zoot suit-influenced clothing and language. Thirty years later his pachuco songs were the basis of the Luis Valdez play, “Zoot Suit,” that told the story of cultural clashes in the time of anti-Mexican sentiments.

Lalo would go on to write songs about labor activist César Chávez, slain presidential candidate Robert Kennedy, and Chicano journalist Ruben Salazar who was killed by police. He also made serious social criticisms with songs like “No Chicanos on TV” and “El Chicano.”

Subsequent generations would discover Lalo’s music and messages.

“He was the clock of the Chicanos in America,” said Buckley. “And he was always on time.”