Editor's note: Ron MacBain sat down with a reporter less than a week ago to talk about his paintings and the upcoming exhibit of his works at Galeria Senita for the following story, which appears in today’s Arizona Daily Star.

He had a massive stroke at Handmaker Saturday, and died at Tucson Medical Center. It was days before his 90th birthday and a week before the opening reception of the show.

While there will be no services, that reception will continue and be a celebration of a life that brought MacBain — and those who knew him — much joy.

This is what MacBain would like, says his longtime friend Elaine Kuntz: donations to the Benedictine Convent and, “he wants people to take a friend to lunch, have a glass of Chardonnay and shop at the Dollar Store.”

Ron MacBain’s life has been steeped in flowers.

He worked with them through his floral shop, and then with his acclaimed garden at the Winterhaven home he shared with his partner, Gustavo Carrasco.

Today, health issues keep MacBain from growing flowers. Instead, he paints them. A show of his works — the first he’s ever had — opens with a reception Saturday, May 6, at Galería Senita.

For a quarter of a century MacBain owned The Plantsman. Before he sold it in 1999, he had established a reputation as the florist in Tucson. He and his 17 employees filled the massive behind-the-altar window at St. Philip’s in the Hills with flowers on Christmases and Easters. He made the floral arrangements for a dinner with the Dalai Lama when he came to Tucson in 1993. He created elaborate and gorgeous centerpieces for a number of years for the Angel Ball.

After he sold his shop, he and Carrasco created a magical garden at their Winterhaven home, filling it with colors and blossoms that attracted painters, photographers and garden lovers. “I was painting my flowers before I had a palette,” he says.

Working in a scent-filled space populated with flowers isn’t possible anymore: Carrasco died in 2011 — the two had been together 60 years — and last year, MacBain, who will celebrate his 90th birthday May 4, was diagnosed with colon cancer. Two subsequent heart attacks meant he couldn’t have the required surgery, and a bad back keeps him in constant pain. The days of picking up the big blue pots in which he grew his flowers were gone. Finally, he realized he could no longer live alone. Last August, he moved to assisted living at Handmaker.

But he could not leave his flowers behind.

Now, he makes his garden grow with oil and canvas.

MacBain sits in his tiny apartment at Handmaker surrounded by photographs of Carrasco, religious statues (he sold religious antiques after he left the floral shop), photos of his Winterhaven garden, and stacks of his paintings, all of flowers.

“I really don’t know how to paint other things,” says MacBain, who seems eternally young, even with his walker, which he uses to get around and which he has jiggered to serve as his easel. There is always a canvas with him.

“I think I’m in the flower shop and arrange on canvas the way I would in a vase,” he says, sitting next to a window with sun streaming in on his nearly lineless and constantly-smiling face.

“I haven’t left my gardens. I save my back, sit and create.”

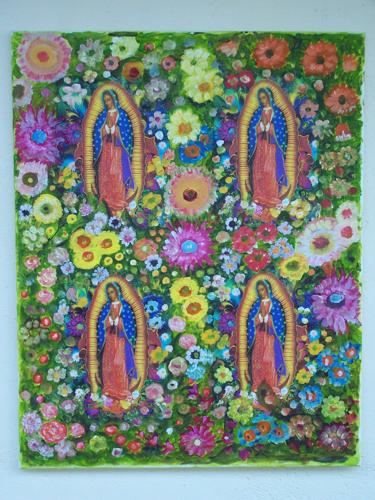

He has a weakness for sunflowers (“I think the whole world loves sunflowers,” he says), and bursts of yellow blooms pop up in most of his paintings. But he is not stuck in a sunflower world. He often incorporates churches, Our Lady of Guadalupe, chile ristra, oranges or lemons and other blossoms into his works.

Ideas come from the memories of his garden and his florist shop. But they also come from such places as the lemon tree in the patio of Handmaker, photographs and grocery store ads.

“I get inspired by fruit ads in the paper,” he says as he points to a painting with oranges spilling out of a basket alongside bright yellow sunflowers and a deep red string of chiles. “This was based on an Albertsons ad.”

Sometimes a work sells — he gets $60 to $120 for one, about what some of his more elaborate floral arrangements once cost — but that isn’t why he paints.

“The joy I’m getting fills me so much,” he says. “I wouldn’t want to do anything else.”