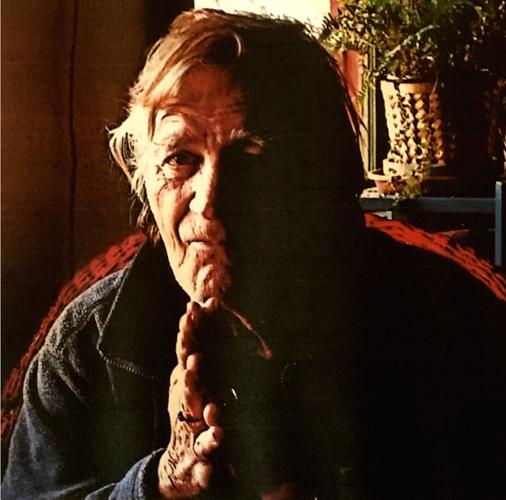

James G. Davis had a quiet voice — “No one could ever hear him,” said his wife, Mary Anne.

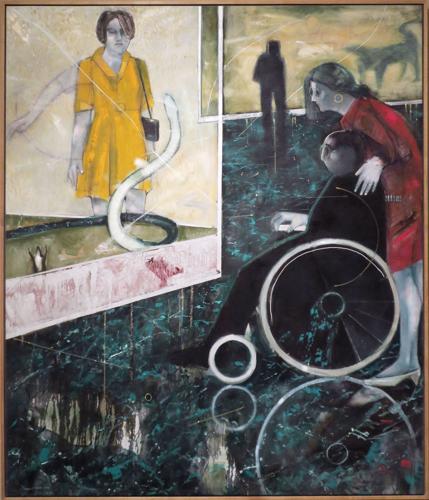

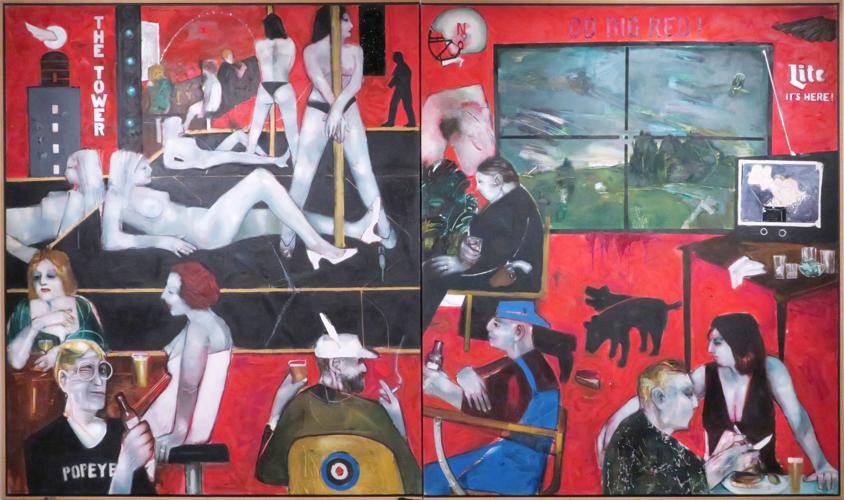

It was his paintings that spoke loudly, and with eloquence, humor and rich narratives. The works — often large-scaled, colorful and complex, and always imposing — have been shown across Europe and America, and are in collections of such museums as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery and Hirshhorn Museum, both in Washington, and the Tucson Museum of Art.

The University of Arizona professor emeritus succumbed to pneumonia late last month at his home in the Oracle artist commune Rancho Linda Vista, where he has lived since he came to Tucson in 1968. His wife, also his muse and frequent model, was with him. He was 85.

Davis, said Terry Etherton of Etherton Gallery, was one of the best artists living here.

“His large-scale paintings are just spectacular,” said Etherton, who has three of Davis’ works hanging in his gallery. “Bold, edgy. … His work is almost reportage. They reflect his travels and his experiences.”

“There’s nobody (here) that’s had a bigger career,” said artist and Davis friend Jim Waid, whose own career is impressive. “He showed in Berlin, New York — he was a force of nature.”

“Bizarre

and interesting”

“His life was totally bizarre and interesting,” says Mary Anne Davis about her husband.

James G. Davis was born in Springfield, Missouri, one of six brothers. His mother died when he was just three, and the children were scattered around. While the older ones went to various family members, he and his younger brother were sent to an orphanage. About a year later, his father managed to bring them all back together.

He was 11 when a train accident left him with a permanent injury. “His brother and playmates would go to the trainyard and chase the cars,” said Mary Anne. “They had a game they called, ‘Dare.’ Jim went under a car and lost half his foot.”

When he recovered, his family moved to Wichita. He dropped out of school when he was in the 9th grade and survived on odd jobs, finally landing one as a bellhop. “He was there for 10 years,” said Mary Anne. “He became night captain with only half a foot.”

While he struggled to survive, he drew. And he loved it. He eventually went to Wichita State University, where the head of the art department told him that if he could pass the entrance exam they would admit him. He passed and eventually became so proficient he was leading classes.

That’s where Mary Anne met him.

She had signed up for a class he taught. “I got such a crush on him,” said Mary Anne, whose relationship with James lasted 54 years. During a break in one of the classes, she decided to stay and paint while others went out for coffee.

“I turned around and Jim was there. He said, ‘Do you want to go get a beer?’ I put my brushes down and we went to Pizza Hut, got a beer, and we never went back to class.”

Life in Tucson

Davis got his MFA and he and Mary Anne eventually settled in Tucson, where Davis’ friend, artist Bruce McGrew, clued him in on an opening at the UA and a place to live at Rancho Linda Vista.

The Davises’ son, Turner, also an accomplished artist, was born and grew up on the ranch. At the UA, he took an undergraduate class from his father.

“The first two weeks of class, he didn’t say anything to anybody,” recalled Turner, who teaches at Arizona State University. “He just walked around. What he was doing was looking, really looking.”

Really looking was key to his teaching, and to his art. “A lot of his paintings are about the observations of everyday people and their struggles and pursuits,” said Turner. “He was the champion of the everyman. There’s a struggle to represent the daily conflicts and loneliness and aspirations of the people all around him.”

Waid finds Davis’ paintings of bar scenes particularly intriguing.

“They are big, big huge paintings. They are pretty amazing and you realize there’s always the observation of the world around him in there. But then he would stick in a collage just to shake things up.”

Davis’ commitment to work was deep and constant. He painted when he traveled to Germany, had a studio at homes in Colorado and Nova Scotia, and kept a studio at Rancho Linda Vista.

“He was extremely disciplined,” said Turner. “He got home and would go to the studio every day. He taught me a ton about that discipline.”

“His commitment to his work was phenomenal,” recalled Waid.

Still, he made time to travel and to collect an odd assortment of objects that would crowd his house and studio, perhaps for inspiration.

“In his house, there was a stuffed gorilla in one corner, papier-mâché men, a collection of all kinds of strange, Davis-like things,” Waid said. “Every shelf was jam-packed with strange things; it was surreal and wonderful.”

“Big gruff guy”

Davis could be imposing.

“When I first met him, I was a little intimidated by him,” said Etherton, who first showed Davis at his gallery in 1982.

“He carried himself as a big gruff guy, a little difficult, a little argumentative. I think he would antagonize just to get to people.”

At the same time, Etherton said, “Jim was incredibly easy to work with. He was always incredibly respectful.”

Davis retired from the UA in 1990, and filled the following years with travel, exhibitions and, especially, painting. As he grew older, he slowed down, and stopped painting about five years ago. But he took up the harmonica, and found joy in playing it for others.

“I’ll miss his shuffling around the kitchen and sitting down and playing harmonica for us,” said Turner, who remembers the long walks he took with his father when he was a young boy.

“He would tell me things, talk about metaphor,” he said. “I’m still trying to understand the concepts he talked about. I’ll miss those mysterious conversations."

“He melded into a very beautiful person, so sweet and gentle,” said Mary Anne. “He wanted to go somewhere every day, he loved a glass of wine, and he never stopping saying, ‘I love you.”

A celebration of James G. Davis’ life is planned for 2 p.m. Oct. 22 at Rancho Linda Vista.