Phil Carlin was 5 years old the first time he saw his name on the marquee.

He’s 81 now and he’d like to see it one more time.

But this time it wouldn’t say “Phil Carlin, Musical Marvel”; it would say “ ‘A Dance Not Easily Done,’ A Ballet In Three Acts by Phil Carlin.”

His ballet is quite possibly the first ever written about a Native American. It’s the story of Changing Woman, inspired by an artist Carlin met in Albuquerque, New Mexico, who is split between the tribal traditions she grew up with and her desire to create art that goes outside the margins of those traditions. She ends up leaving the reservation and seeking happiness on an easel in a world that’s far different from the one she left.

Carlin spent 1,700 hours writing the 90-minute score, which he began in 2002. It took 35 hours to write the story.

And he hopes one day people will experience it on stage.

“I don’t seriously know if this will be mounted before I die,” he conceded. “It is on my bucket list.”

The biggest hurdle for Carlin: introducing himself to the ballet world.

A child prodigy and a

‘man-sized pay envelope’

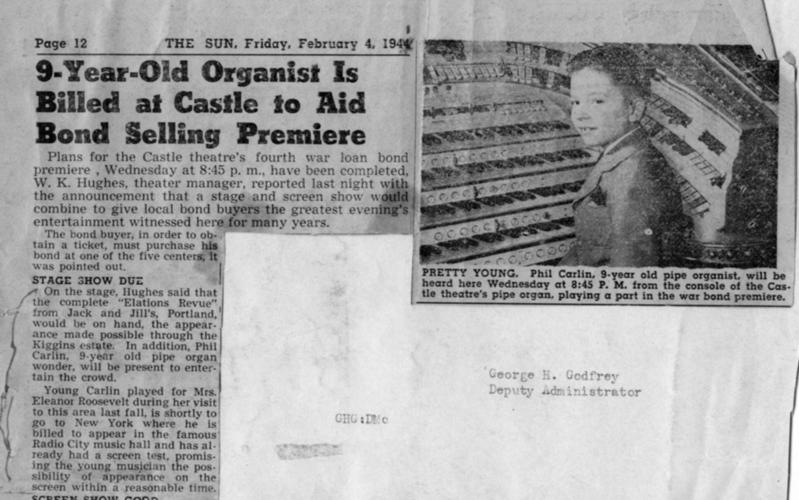

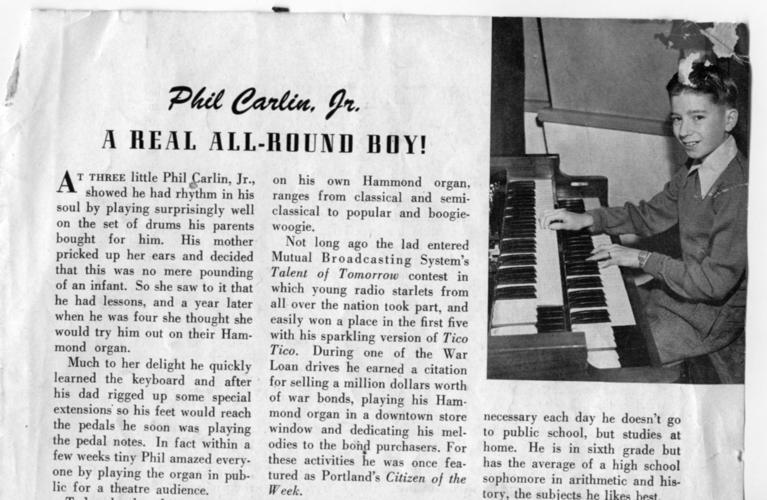

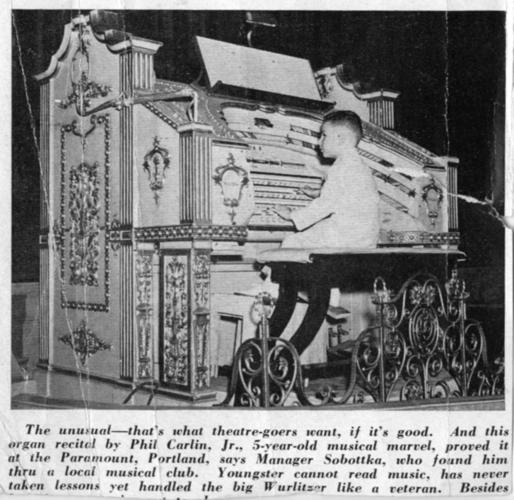

Carlin was 5 when he first appeared in the local papers in his native Portland, Oregon. They called him a musical wünderkind who couldn’t read a lick of music but could pound out a inspired jazz tune or light classical score on the gigantic Hammond organ.

The cherubic-faced little boy learned to play by rote, taught by his organ-playing mother. He was so short his feet couldn’t reach the pedals so his dad added extensions. Every weekend, the tyke would climb up on the bench and play mini concerts of classical music, jazz, boogie woogie and pop tunes between films at his parents’ Lincoln theater in Portland.

Word spread quickly and Carlin soon got gigs at other theaters and venues. Some of the newspapers started calling him “Portland’s Boy Wonder Organist.” He played for Eleanor Roosevelt when he was 7, and two years later sold a million dollars worth of war bonds by playing song requests at $25 a pop. Actually, he says now, it was more like $250,000; a local company kicked in the rest.

He also had his own radio show on KALE in Portland that was broadcast over the Mutual network, and he earned a footnote in the state’s broadcast history as one of the first people to perform on TV.

“We would perform in 15-minute segments,” he recalled, sitting in a University of Arizona-area coffee shop in mid-June. “We would sometimes get pre-empted by the fights.”

A local magazine noted that the boy, with all his performances, was drawing “a man-sized pay envelope.”

Carlin continued playing well into his teens and through college. He went to Oregon State to study science and met jazz pianist Dave Brubeck just weeks before the seminal cool-jazz composer and pianist was featured on the cover of Life magazine. Carlin formed an ensemble with a couple other musicians and tried to emulate Brubeck’s style. They weren’t great, he confides now.

Carlin landed a job out of college with the Atomic Energy Commission in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He was there just two months before being drafted into the Army. He served two years and met good musicians who taught him how to play in a band. When his tour ended, he left the military and returned to his job in New Mexico.

Taking a shot at music

Carlin was a performer and no matter how he tried to convince himself otherwise, it was what he knew best. So three years into his job with the Atomic Energy Commission, he returned to music.

He joined a traveling quartet that included a pair of vocalists and played in Los Angeles. He went to Vegas and landed a job at the Vegas Stardust.

“We were on 24-hour call. If someone didn’t show up, we had to go in. The Vegas Stardust had 24 hours of music, no stopping,” he recalled. “I had to crawl over the organist so that the music wouldn’t stop.”

It was the 1960s and entertainment jobs were plentiful. Using a portable organ, he played bossa nova, jazz, pop standards and light classical, all at a danceable pace, at clubs up and down California, Oregon and Nevada. For almost two years, he was half of a comedy duo that featured him on piano and his partner singing. He returned home to Portland and landed a standing gig as house musician at the Portland Hilton Hotel six nights a week. The money was good.

Until it wasn’t.

By the late-’60s, things changed.

“The music industry was going down quickly. The idea of being a six-night-a-week musician was at the beginning of the end,” Carlin said. “Unless you wanted to be in a rock ‘n’ roll band and tour, that was the only other option. That was really not the kind of music I liked.”

New town, new direction

With a wife and child to support, Carlin moved to Tucson in 1969. He had earned a master’s degree in business from the University of Portland and was accepted into a doctoral program in child guidance at UA. On weekends, he played organ at the Jester’s Court, “the only place that Phoenix recognized in Tucson,” he said.

“They had two live panthers that strolled back and forth behind the bar,” he added.

Carlin said he had completed all of the coursework for his doctorate but dropped out before writing his dissertation. He had learned that the best job he could get with the degree was teaching sixth grade, so he took a job with a Native American student achievement program on the Tohono O’odham Nation. He was there a couple years before landing a job with the city of Tucson in 1973.

For 21 years he worked with Tucson’s fire and police departments, implementing training procedures. His most notable achievement was launching the FEAT — First Encounters Acceptance Test — exam for the fire department, which emulated the experience of actually fighting a fire.

“They would call me in the middle of the night if they were laying lines, which means they had a real fire going,” he said of how he developed the program. “And I would go out there and watch what they did, and what they did was put up ladders and draw hoses and carry stuff. And when they would get the hoses going, they would handle the hoses. Very heavy, tough work. Nobody stopped. They kept going until they got the fire out.”

The test opened the door for women, who until then had been tested laregly on whether they had the physical strength to complete push ups or run obstacle courses.

“It wasn’t that women never got on a (hiring) list; they never passed anything. I thought there’s something wrong with that. Doesn’t make any sense,” he said. “We had the first woman ever selected as a firefighter in Tucson (because she) passed the (FEAT).”

One last item

on the bucket list

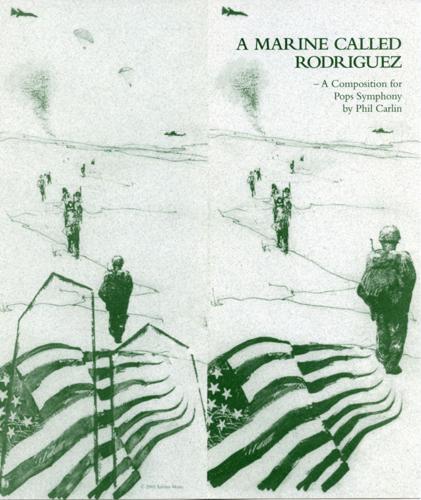

Carlin retired from the city in 1994 and focused his energy on composing. He started writing jazz music for organ and piano in 1998 and recorded four CDs at Jim Brady Recording Studios. He tip-toed into classical music with “A Marine Called Rodriguez,” which was inspired by a Tucson veteran he had befriended. He composed “Marine” for the Tucson Pops Orchestra, which premiered it in 2002.

“It’s a marvelous piece and there’s a lot of depth to it,’ said Tucson Pops Conductor László Veres. “He writes very nicely. … It uses all kinds of melodies to bring the story together.”

That also was the year he started writing “A Dance Not Easily Done.” He wrote the story ballet, inspired by the Native American painter he had met years earlier, much in the tradition of European ballets.

Carlin compiled a chunk of the score from music he had composed years earlier. The music is a rich soundscape of modern styles, from traditional classical tunes to rich piano-driven jazz movements with piercing horns, and New Age-style melodies punctuated with strong Native American accents.

The piece did not come easily. Carlin was on his fifth marriage, and it was on the rocks. He said his wife told him that she wanted out. The stress proved too much and Carlin suffered what doctors later said was likely a stroke and seizure.

Over time, he regained his strength, but there are lasting effects. Carlin can’t remember names as easily and sometimes struggles to find the right words when he’s talking. He said his doctors told him he suffers from an altered mental state. However, the father of three was quick to add, “Nothing’s physically wrong with me.”

Carlin recorded a demo of the ballet with Tucson musicians and Native American jazz vocalist Mary Redhouse. The 2005 Grammy nominee and Tucson resident sings in a chanting vocalise that dips into a horn-like scat scaling five octaves.

Carlin is using the recording to pitch the ballet to companies in England, New York, Los Angeles and Santa Fe, New Mexico, home of the annual summertime Santa Fe Opera festival. He would love to see it on a stage one day.

“I want people to walk into the theater thinking they’ve just received a gift,” he said.