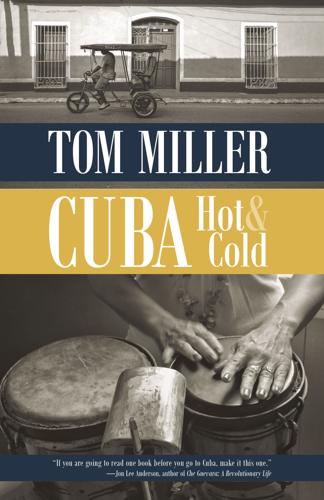

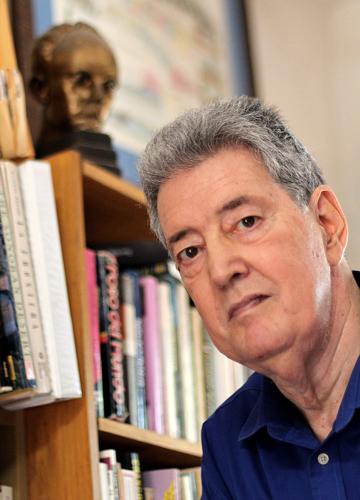

Tucsonan Tom Miller first visited Cuba 30 years ago. He has returned often, writing about a Cuba most don’t get to see. His books include “Trading with the Enemy” and “Revenge of the Saguaro.” This is an excerpt from his latest, “Cuba, Hot and Cold:”

José Martí, leader of Cuba’s nineteenth-century independence movement, is said to have had a voice that sounded like an oboe. Perhaps that’s why the country has so many oboe players. I took oboe lessons in Havana when I lived there in the early 1990s and wrote about them at the time. I was hoping to improve my mediocre oboe skills acquired during junior high school, and frankly, I wanted to show readers that contemporary music in Cuba was more than just salsa and reggaeton. I succeeded with the latter, but far less with improving my ability. I even had trouble with the ducks in Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf. And so I put my oboe on the top shelf in my Arizona office where it gathered desert dust. I’d glance up at it now and then with a sense of forlorn pride, reassuring myself that I owned a quality instrument that I once played with some gusto.

Dust gathered for some twenty-five years. At times I considered the instrument little more than a “dull black tube scattered with metal keys,” as Blair Tindall describes her first oboe in “Mozart in the Jungle—Sex, Drugs, and Classical Music.” During those years I led literary tours of Havana and beyond. One autumn as I began organizing the following January’s trip I looked up at the dust-encrusted oboe case and thought, if I leave it there another twenty-five years, half a century’s dust will have accumulated and not one orchestra will ever have tuned to my oboe’s A-above-middle-C, as is the global custom.

Back when Adlai Stevenson was the Democratic Party’s standard-bearer my family lived across the street from an elementary school named for the Frenchman Lafayette; my parents were active in school affairs there. One of my earliest memories is a pile of musical instruments in the living room growing in size as parents dropped off unused instruments to be distributed among primary school children. I wished that pile still existed so I could donate my unused oboe. Instead, I packed it on my next trip to Cuba.

Whatever happened to my old oboe teacher in Havana, Jesús Avilés? He had, I learned, moved to the city of Matanzas, sixty-five miles east. In the capital he was the principal oboist for Cuba’s Orquesta Sinfónia Nacional, but in Matanzas he taught oboe to eight students. I took my Literary Havana group to a publishing house in Matanzas one day and invited Jesús to join us afterward at the Velasco Hotel’s dining room. (He was remarkably easy to find.) Before lunch I ceremoniously presented him with my old oboe and asked him to give it to a deserving student. There was a smattering of applause, and I surprised myself by getting all choked up for parting with a token of my youth. We were served a choice of pork or fish.

The oboe, made by the Robert Thibaud company in Paris, went not to a student right away but to Pedro Puentes, one of Havana’s two woodwind repairmen. Pedro lived in Marianao, a suburb that foreigners see only on their way to the Tropicana Cabaret. He made double reeds for oboes, the oboe d’amore, English horns, and bassoons, and sold them for about a dollar each. Pedro overhauled my old Thibaud — tightening screws, adjusting pads and metal, replacing cork, and repairing slight leaks. “When Pedro finishes restoring it,” Jesús said with quiet pride, “it will be good as new.” Much of Marianao, on the other hand, was in worse shape than the worst oboe, strewn as it was with abundant potholes, cracked sidewalks, and homes in desperate need of rewiring, replumbing, repainting, and reconstruction. Marianao looked like no one had tended to it since Batista left Cuba.

Pedro led me to the small workbench in the second-floor bedroom to which the city’s woodwind musicians brought their ailing instruments. His granddaughter, who lived with him and his wife, moistened a double reed, climbed up on the double bed, and tooted a couple of scales on her father’s oboe. Her eight-year-old right pinky practically reached the low C, C#, and D# keys. “I don’t want her to decide on the oboe at her age,” Pedro said. “She should try other instruments as well.”

The good-as-new Thibaud was now in the hands of Jesús, who started considering each of his students. Eventually he decided upon fourteen-year-old Lorena Gómez, who had been playing oboe since she was ten. Her qualifications: “Dedication. Ambition. Potential. Family support. A sweet tone comes out of her instrument. She wants to play oboe professionally.”

Lorena, her parents, Jesús, and his wife met me at the bus when I next traveled to Matanzas. Jesús had recently suffered a severe bout of pneumothorax, more commonly known as collapsed lung. Two procedures at a Matanzas hospital were required to eliminate a bubble in one lung and to fix a perforation in the other. In all, he spent twenty days and zero pesos in the Faustino Pérez Hospital. By the time I reached Matanzas the good news was that Jesús was in full recovery mode. The unfortunate news was that his lungs could no longer generate sufficient air pressure to vibrate a reed and produce the oboe’s tone. After more than fifty years playing the oboe throughout the Americas and Europe, sixty-eight-year-old Jesús Avilés’s oboe-playing days were over. Sure, he could still teach—embouchure, fingering, posture—but he couldn’t coax even a squeak out of his instrument.

The six of us walked a few blocks to the José White Concert Hall where Lorena set up her music stand on stage, put her moistened double reed in the oboe, and, alone with an audience of five, played an Albinoni oboe concerto. She stood about five-foot-four, dark hair, dark eyes, light skin, and a teen-age smile. She wore a pretty pink dress for the occasion.

Nicely played, we all agreed. She showed poise where she might have shown anxiety, composure where tension wouldn’t have surprised us. “¿Ves?” Jesus motioned. “See?” We all congratulated her and walked over to a state-run snack bar on Parque de la Libertad. On the way we passed a recently established hot spot where giggling young matanceros tried out their smartphones for the first time. “You are all invited to lunch,” Lorena’s dad, Orlando, proclaimed to us all once we arrived at the snack bar. “We have plenty of shrimp at the house.” Although a college grad, he chose to work at the Restaurante Italiano, part of the Meliá hotel complex at the nearby beach resort of Varadero. The tips were better than a government salary.

We took a cab to their home in Barrio Peñas Altas, climbed to the second floor of a duplex where their dog Sofi greeted us, and sat on the back porch with a lovely view of Matanzas Bay. While Orlando prepared lunch Lorena played a short piece on their painfully out of tune upright piano.

Each province has a music school named for a musician except, curiously, for the one Lorena attended in Matanzas. It was named for Alfonso Pérez Isaac, active in the Castro revolution and the Angolan War. The list of martyrs and the list of schools must not have come out even.

Lorena was soon to take a national exam to qualify for the music conservatory in Havana where they taught music theory. She’d play in ensemble groups there and learn how to whittle her own reeds. “The state supplies low-quality Chinese oboes and plastic ones.” Jesús made a face. “She’ll have no trouble getting into the Havana school with this new one.” As a light rain fell we spent the afternoon taking pictures of each other and eating shrimp. We could hear freighters plying Matanzas Bay.