The Genesis of ‘Erskine Caldwell,

Margaret Bourke-White, and the Popular Front’

I think somewhere, deep down inside, there has long existed in me a sense that I have wanted to show my father how much I appreciated his being my father.

It wasn’t that I owed him something. Nothing like that.

I didn’t grow up with him in my house and because he was a very private (shy) man, I never knew much about him.

I don’t even recall reading his books while he was still alive. I’m sure that hurt him, or would have if he’d known.

But then again I never got the real story from him about the Nazi helmet on his bookcase, the one with the bullet hole through its temple, which was the spark for the whole idea.

So when the fulcrum moment came several years into my English literature doctorate — just after I passed my orals for which I had read almost everything by Sir Walter Scott and lots and lots of travel literature, including some of my father’s — I experienced an apotheosis.

The Arizona faculty kept browbeating us grad students to explore new territories, press into the unknown. Reading the substantial cache of material that had been written about my father — the standard biographies and the literary criticism — I realized that his year in Russia, perhaps by his own design, was a tabula rasa.

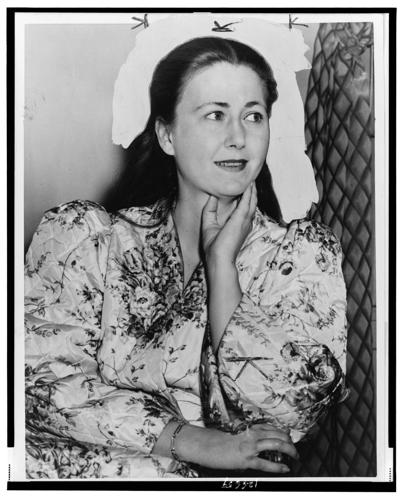

Eureka! 1941 was a momentous summer in world history (Operation Barbarossa was the code name for Nazi Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II) and in my father’s and Margaret Bourke-White’s lives, little had ever been written about their at-least-partially politically-motivated Russian hegira, biographically, lit-critically, or personally.

By exploring this unmapped literary territory I could both repay my perceived filial debt and discover what exactly went on in 1941.

And so in the spring of 2012 I set out on my own Russian adventure.

It took several years of research and included multiple visits to his archives at Syracuse, Dartmouth, and Georgia.

As I trailed one lead after another, from the Library of Congress, through contemporary newspapers, dozens of memoirs, and his own memorabilia, and even to the FBI and the American Embassy in Moscow, gradually I began to sense what fortuitous pioneers he and Bourke-White were, how boorish each could be, but especially how important this summer was in the memories of the few journalists in Moscow then. And how quickly and sadly it ended for him and Bourke-White.

— Jay E. Caldwell

Excerpts

Alice Moats’ memoir of the summer, “Blind Date With Mars,” published in 1943, focuses on her fellow journalists, in particular their appearance and behavior. Here she describes the Caldwells when she first encounters them at a remote airport in China.

In “Blind Date With Mars” she writes a gadfly gossip columnist’s recollection of her own 17-month round-the-world journey.

Moats’ schadenfreude over the Caldwells’ plight in Lanzhou is evident as she first encounters them when she disembarks from her own Chongqing flight.

“Margaret Bourke-White was standing on the field with her husband, Erskine Caldwell, entirely surrounded by 280 kilos of luggage. I had met them casually in Chungking, where they had picked up their Soviet visa. There was a great difference between their experience and mine, for, as Oumansky had made all arrangements for them from Washington, they didn’t have to wait at all. They were treated as very big shots indeed, got a ticket on the plane with no difficulty, and were allowed to carry all the excess baggage they liked. Trailing clouds of glory, and very pleased at being the first Americans to travel to Moscow over the air route, they left Chungking 10 days ahead of me. At Lanchow their plane broke down and they spent what I gathered were nine very boring days there.”

Nonetheless, Moats’ description of their crossing of China is certainly more thorough than either of the Caldwells’ and possibly more reliable. She expresses a kind of ambiguous displeasure at the couple’s haughtiness, while admiring their chutzpah. She introduces herself in “Blind Date” with this snarky, jealous and backhanded dig at the Caldwells, and at Bourke-White in particular: “In Chungking I didn’t become an intimate friend of the Generalissimo and Madame Chiang; in fact I never met them. In Russia I didn’t interview Stalin.”

At their first overnight stop, in Süchow, accommodations were rudimentary, “an adobe resthouse,” as Moats describes it.

Though neither Caldwell nor Bourke-White mentions their vain attempt to charter a plane privately during the four days they were marooned in Hami, that clearly seems to have been the case. They even got Moats to agree to go in on the cost. Moats shakes her head in wonder at the Caldwells’ willingness to bargain over a $3,000 charter. But that plane never materialized.

Moats provides an unforgettable image of Caldwell and Bourke-White there:

Erskine set up his typewriter on a balcony and spent the afternoon composing telegrams to his Russian publisher and other important people in Moscow, asking them to use their influence to get us a private plane. As he finished each wire he handed it to Peggy, who would read it over with gasps of wonder. “Splendid, Skinny darling, simply splendid!” she would exclaim. “What a great writer you are!” The admiration she felt for her husband was quite awe-inspiring.

Moats does admire the Caldwells’ harmony, even if it excluded her: “With few books to read, I had to depend principally on the servants for entertainment. Both the Caldwells were engrossed in work most of the day. Aside from that, they moved in an atmosphere of such connubial bliss that I didn’t like to intrude.”

The following describes the journalists’ final day on the Front, and herein is described the gathering of the helmets (“Rosebud” for me).

Their final stop was the town of Yelnya itself, now mostly ashes and chimney stacks, and a few damaged survivors. Bourke-White’s two published photos of the town capture this desolation. One is of a symmetric array of three ruined chimneys, the other, shot from a low angle, is of a pair of Russian sentries guarding what remains of the Yelnya Cathedral. To the left stands a chimney stack with a fireplace connected to it; in the center is a steepled tower, around the top of which protrudes an octagonal observation deck; to the right, and farthest away, crouches a low, iconic, “coppery-green” onion-topped church. It had become a dormitory for the soldiers.

In Yelnya’s streets Philip Jordan found a variety of poignant items: “Here there is a samovar with a bullet hole through its jagged zinc sides, here the remains of the clock by which some child once knew when it was time to go to school, here a garden hoe or a piece of shattered bed on which some innocent lay down to rest.” Seeing the remains of what had once been Yelnya, Henry Cassidy thought of Paris, where he’d been a correspondent when the Germans invaded in June 1940. By contrast, the Nazis had treated the area with kid gloves: “There, after the fall of Paris, I found the battle had passed swiftly and lightly over most places, punching only a few holes in the village here, wrecking a crossroads there. Around Yelnya, all was consumed in a frightful, all-devastating struggle between two giants, fighting savagely to the death.”

It is not possible at this resolve to know how Caldwell himself behaved on the battlefield at Yelnya, whether he was an entranced tourist and relic-gatherer or an insightful and thoughtful war journalist. But the narrator of Caldwell’s “All-Out on the Road to Smolensk” is devastated. He has now reached the forbidding center of this holocaust and come face-to-face with death itself. He observes, “I walked over the battlefield for several hours looking for some sign of life, but all was dead.” No crows. No vultures. No homeless dogs. Even the field mice in the dugouts were dead. So he takes an inventory, and in this inventory the combatants come back to life in the mind of the reader. There Caldwell is no longer writing of his own experiences as do the other diarists, nor attempting to create an accurate account of the trip, and he is not even a journalist at this moment. Caldwell rehabilitates the individual lives of these faceless soldiers through the detritus and impedimenta of their deaths:

They had filled their dugouts with many of the comforts of home. All of them had wheat straw on the floors, and most of them had straw-stuffed mattresses. Some of them had books on shelves; the shelves had been carved in the clay walls. There were vodka bottles, both full and empty. There were musical instruments and games.

In one trench, laundry was still hanging on a line — two shirts, several socks, and a piece of material that looked as if it had once been a tablecloth. In another trench I found a pair of boxing gloves, a harmonica, a samovar, and a wall calendar with heavy pencil marks drawn through all the dates of the month except the last nine.

The battlefield was covered with all the odds and ends of war and peace. There were torn and shattered gas masks and helmets: there were Iron Crosses and regimental insignia; there were letters from home and photographs of children. There were belts, boots, swords, pistols, rifles, cigarettes, magazines, buttons, pencils, coins, diaries, bottles, first-aid kits, tins of fish, wristwatches, dispatch cases, keyrings, pocket knives, can openers, pocket books, bank books, finger rings, blood-soaked bandages, unused cartridge clips, and rain-soaked bread.

The closest he is able to approach an actual human being is the only marked grave he finds on the battlefield.

On a mound of earth under what once had been a tree I stumbled over a carefully lettered marker on the grave of a German soldier. The board had been hewn from a birch tree, and an inscription had been burned on it with a red-hot iron. Since the marker had been lettered and erected with such care, it was evident that the German had died and been buried before the storm and furore of battle.

The birch marker was inscribed:

In Memory of Max Goerighter

Died September 2, 1941

Of all the thousands of Germans and Russians who died in the Battle of Yelnya, only Max Goerighter’s grave is marked. When I was there, the slender birch post over the grave had fallen down, and I pushed it into the soft earth as firmly as I could before I left.

We must guess whether Caldwell pushed the gravemarker into the earth to erase Goerighter’s Nazi subjectivity or pushed it into the earth more uprightly and firmly so as to restore his basic humanity.

In this ambiguous act at the German soldier’s grave, Caldwell embraces the reality and horror of war, and leaves it for us to parse. He never tells us his thoughts. Was his act of acquiring of Herbst’s Wehrmacht helmet simply one of youthful exuberance, thoughtlessness, souvenir hunting? Were the German war dead less meaningful than the Russian dead? Or was it an acknowledgement that, in the end, all war is a singularity and he was Goerighter’s and Herbst’s personal witness? Now, walking back across the battlefield to join his wife and fellow correspondents, he had already begun his journey home.