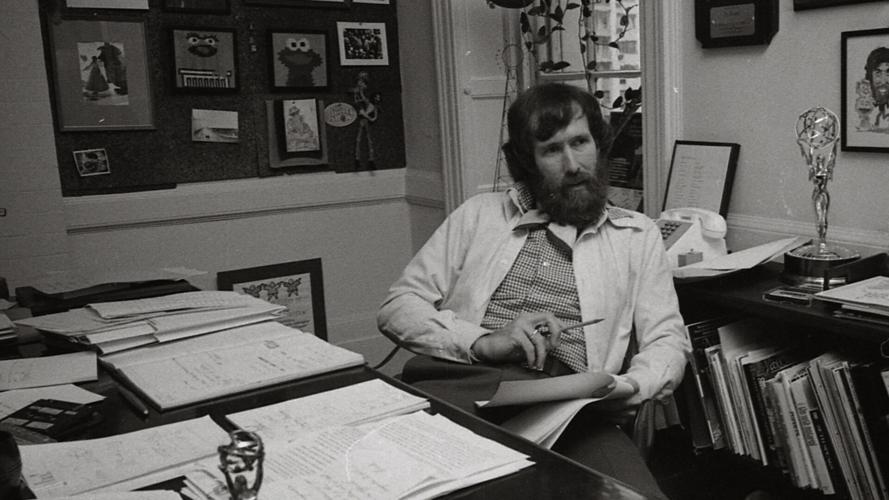

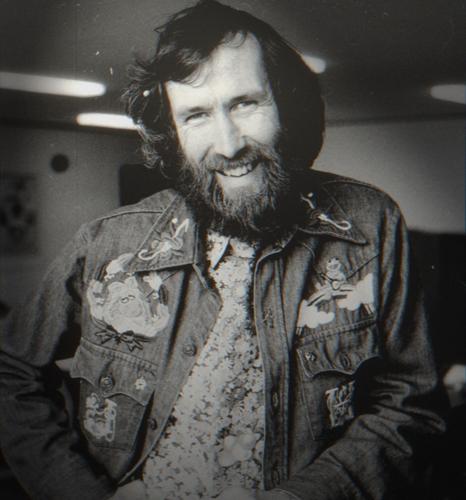

“Jim Henson Idea Man” should have been titled: “Jim Henson Workaholic.”

In the Ron Howard documentary, Henson is rarely pictured without a pile of felt or a herd of Muppets more than an arm’s reach away.

That split ping-pong ball and woman’s coat (which turned into Kermit the Frog) was only the start.

Henson, in fact, didn’t just want puppet shows. He was interested in creating ballets and Broadway musicals. He started by doing commercials, then branched into small films and, his goal, television.

There he scored on “The Jimmy Dean Show” before making his mark with “Sesame Street.”

The PBS series was in keeping with his hit-and-run philosophy. Commercial-length storytelling had its place on the children’s series.

Howard uses plenty of behind-the-scenes footage to illustrate and lets Muppeteer Frank Oz talk about the Bert and Ernie he and Henson created. Eventually, Oz says, they didn’t need to script segments; they worked “spontaneously.”

Watching the two create the magic is among the documentary’s biggest pleasures. Oz, Henson and other regulars look happy. Equality was key to that.

When Rita Moreno guested on “The Muppet Show,” she took a little more time with a scene and Henson pointed out, “We don’t do overtime here.”

As much a worker as the boss, Henson didn’t let success stifle his vision. When “The Muppet Show” was at its peak, he thought it was time to try something else and moved into movies. While that world wasn’t as forgiving, it did show Muppets didn’t need to be confined to homes.

To provide perspective (and explain Jane Henson’s role in the family business), Howard includes plenty of interviews with the idea man’s five children. They’re cautious about the family secrets and gloss over the partnership Disney created with the Muppets. Coming after Henson’s death, it was wildly unpopular among fans. Insiders worried, too, but the company continued to produce work for all mediums.

At Henson’s funeral, Caroll Spinney, dressed as Big Bird, sang Kermit’s song, “It’s Not Easy Being Green.” The moment captures the loss and, when the other Muppets turn up, demonstrates how difficult moving on would be.

Glimpses of Henson’s experiments are among “Idea Man’s” greatest contributions. A ballet might have worked; a theme park clearly could have given The Muppets more real estate than the attraction Disney afforded.

Moments from “Labyrinth” and “The Dark Crystal” show how Henson might have delayed the onslaught of special effects in fantasy films. (Jennifer Connelly talks about the strange world she inhabited in “Labyrinth” and what it was like to be part of the Muppet world.)

Those moments override the odd interview Orson Welles conducted with Henson. Howard uses it as a frame of sorts but, certainly, there were other interviews that could have provided more insight.

Because Henson was such a seminal figure on television, Howard should have provided some comparisons. How did he play in the puppet world? Was he a teacher like Fred Rogers? A comfort like Shari Lewis? Or was he a Disney-level innovator who deserves a place on the entertainment world’s Mount Rushmore?

“Idea Man” doesn’t oversell but it also doesn’t give Henson the special place he deserves. Broadway canonizes Stephen Sondheim every other year. Television could do the same for Henson. All it would take is interviews with those who tried to carry on after he was gone.

“Jim Henson Idea Man” airs on Disney Plus.