When David Arsenault takes down a worn, leather-bound 19th-century book from a shelf of the Boston Athenaeum, he feels a sense of awe — like he's handling an artifact in a museum.

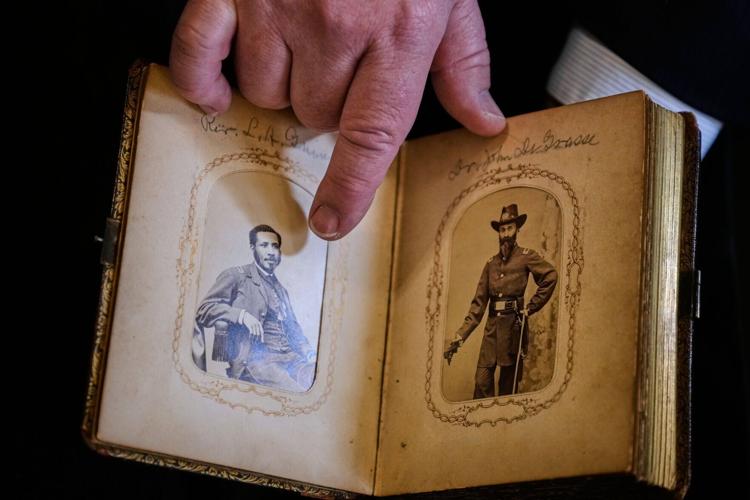

Portraits of Mass. Rep. Charles Lewis Mitchell, left, and Dr. John V. de Grasse are seen Oct. 9 in a photograph album from the personal collection of anti-slavery activist Harriet Hayden, which was printed in the 1860s, at the Boston Athenaeum.

Many of the half-million books in the library's maze of reading room shelves and stacks were printed before his great-great-grandparents were born. There are fraying copies of Charles Dickens novels, Civil War-era biographies and town genealogies. Everything has a history.

"It almost feels like you shouldn't be able to take the books out of the building, it feels so special," said Arsenault, who visits the institution a few times a week. "You do feel like, and in a lot of ways, you are, in a museum — but it's a museum you get to not feel like you're a visitor in all the time, but really a part of."

The more than 200-year-old institution is one of only about 20 member-supported private libraries in the U.S. dating back to the 18th- and 19th-centuries. Called athenaeums, a Greek word meaning "temple of Athena," the concept predates the traditional public library. These institutions were built by merchants, doctors, writers, lawyers and ministers who wanted to not only create institutions for reading but also space to explore culture and debate.

Many athenaeums still play a vibrant role in their communities. Patrons gather to play games, discuss James Joyce or research family history. Others visit to explore some of the nation's most prized artifacts, such as the largest collection from George Washington's personal library at Mount Vernon at the Boston Athenaeum.

Pedestrians walk past the Boston Athenaeum, one of the oldest independent libraries in the United States, on Oct. 9 in Boston.

In addition to conservation work, institutions acquire and uplift the work of more modern creatives who may have been overlooked. The Boston Athenaeum recently co-debuted an exhibit by painter Allan Rohan Crite, who died in 2007 and depicted the joy of Black life in the city.

One thing binds all athenaeums together: books and people who love them.

"The whole institution is built around housing the books," said Matt Burriesci, executive director of Providence Athenaeum in Rhode Island. "The people who come to this institution really appreciate just holding a book in their hands and reading it the old-fashioned way."

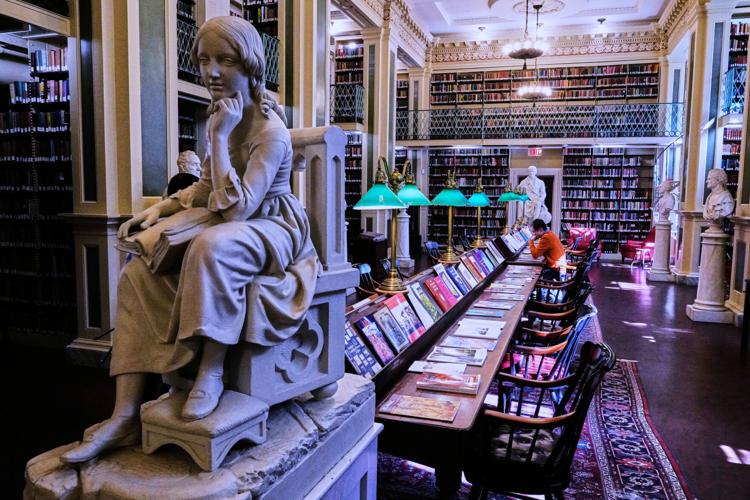

A sculpture of the character Little Nell from Charles Dickens's "The Old Curiosity Shop" is displayed Oct. 9 at the Boston Athenaeum.

Greek inspirations

Providence Athenaeum was built to mimic an imposing Greek temple, and staffers often talk about the joy of watching people enter for the first time.

Visitors climb granite steps and a thick wooden door ushers them into a warm world filled with cozy reading nooks, hidden desks to leave secret messages to fellow patrons and almost every square inch bursting with books.

"It's the actual time capsule of people's reading habits over 200 years," Burriesci said, pointing to a first edition of Little Women, pages and spine proudly showcasing years of being well read.

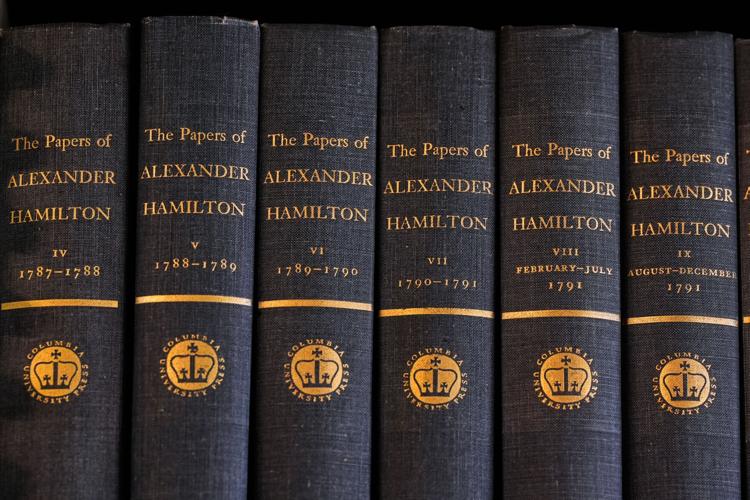

Bound copies of Alexander Hamilton's papers are displayed Oct. 9 at the Boston Athenaeum.

Many athenaeums are designed to pay tribute to Greek influence and their namesake, the goddess of wisdom. In Boston, a city once dubbed "the Athens of America," visitors to the athenaeum are greeted by a nearly 7-foot-tall bronze statue of Athena Giustiniani.

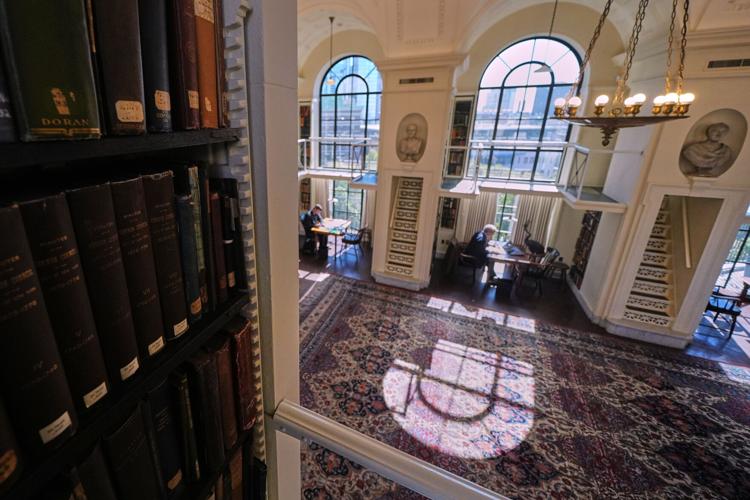

The building is as much an art museum as it is a library.

"So many libraries were built to be functional — this library was built to inspire," said John Buchtel, the Boston Athenaeum's curator of rare books and head of special collections.

The 12-level building includes five gallery floors where busts of writers and historical figures decorate reading rooms with wooden tables overlooked by book-lined pathways reachable by spiral and hidden staircases.

"We're able to leave many of these things out for people to peruse, and I think people can often get curious about something and just follow their curiosity into things that they didn't even know that they were going to be fascinated by," Boston Athenaeum executive director Leah Rosovsky said.

Guests read and work Oct. 9 in the fifth-floor reading room, designated a "silent space," at the Boston Athenaeum.

Safe havens

When athenaeums were founded, they were exclusive spaces that only people with education and money could access.

Some are now free. Most are open to the public for day passes and tours. Memberships to the Boston Athenaeum can range from $17 to $42 a month per person.

Charlie Grantham, a wedding photographer and aspiring novelist, said she first visited during one of the institution's annual community days, where the public can explore for free. She said she was surprised by how accessible it was and describes the space as "Boston's best kept secret — an oasis in the middle of the city."

Some people visit every day to work remotely, read or socialize, Salem Athenaeum executive director Jean Marie Procious said.

"We do have a loneliness crisis," she said. "And we want to encourage people to come and see us as a space to meet up with others and a safe environment that you're not expected to buy a drink or buy a meal."

Best place to live in every state

![]()

Best place to live in every state

What do you look for in an ideal town? Proximity to trails, lakes, and beaches? How about top-ranking schools for your children? Would you prefer a professional or college sports team nearby, or do you prefer museums and art walks?

While Americans opt to move for a variety of reasons, June 2025 data shows that many have decided to stay put for now. According to Harvard University's State of the Nation's Housing 2025 report, residential mobility has reached an all-time low, with just 8.3% of Americans moving in 2024. Moves to the South, historically one of the nation's fastest-growing regions, have also slowed down, with domestic migration dropping by as much as 20% in some southern states.

Despite these trends, towns across the South—and the rest of the United States—have plenty to offer residents. Stacker compiled a list of the best places to live in every state using Niche's 2025 rankings. This list took into consideration cities, suburbs, and towns. Niche ranks places to live based on several factors, including the cost of living, educational attainment, housing, and public schools. Check out their full methodology here.

Many cities on the list are suburbs experiencing growth due to people leaving cities for smaller towns. Other entries include planned communities and older cities that have been revamped, with grassroots efforts focusing on greener ways of living, drawing in new businesses, and encouraging the arts. Towns with large colleges appear regularly, as prestigious universities employ thousands of workers and provide diverse recreational and educational options for families.

Whether you're thinking of relocation or are big on hometown pride, click through to find the best place to live in every state.

Alabama: Madison

- Population: 58,335

- Location: Suburb of Huntsville, AL

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Madison is home to Toyota Field, the stadium for a local minor league baseball team with arguably one of the most eccentric names in sports: the Rocket City Trash Pandas. Madison also has top-ranked schools, borders the city of Huntsville, and offers several small business incentives.

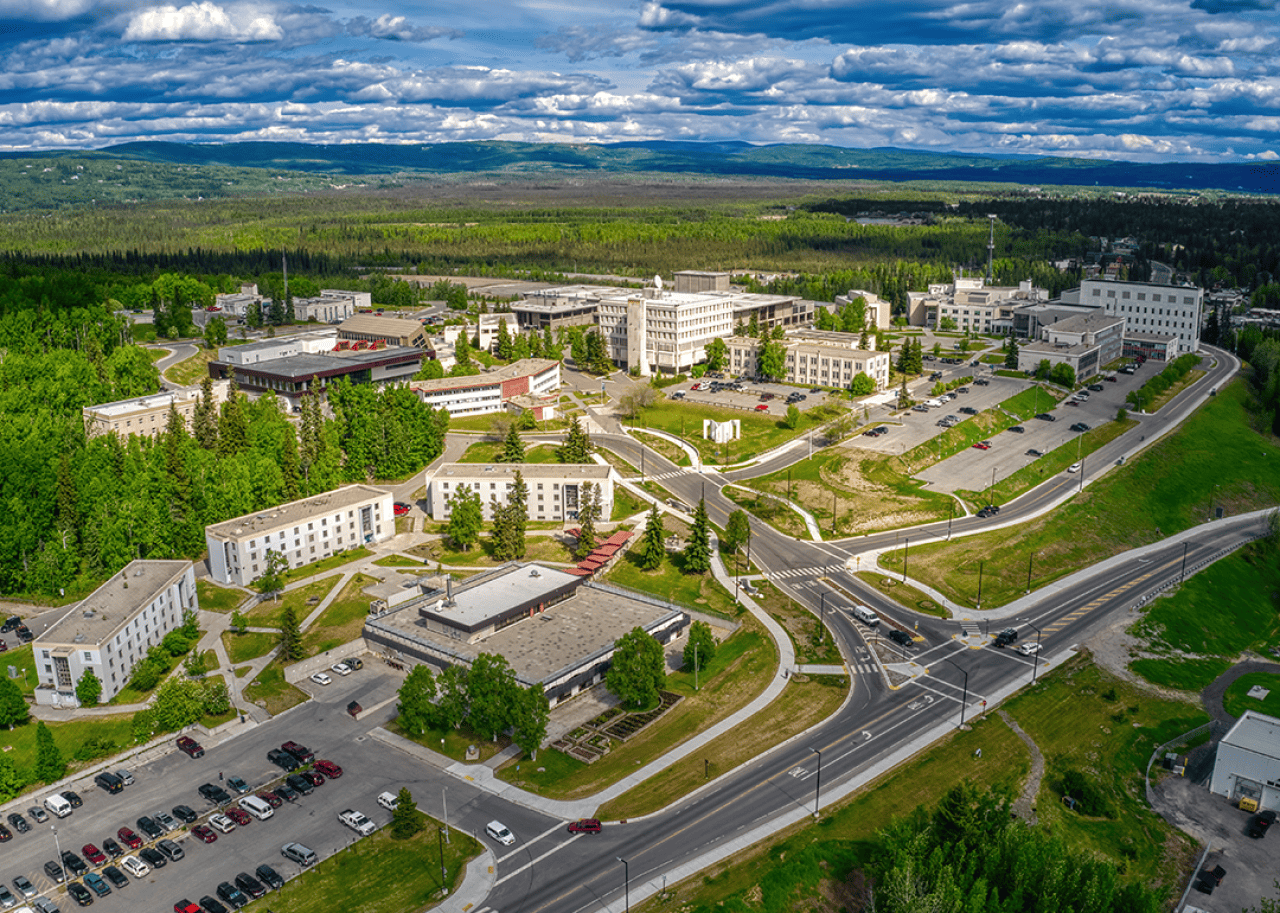

Alaska: College

- Population: 11,730

- Overall Niche grade: A-

- Public School grade: B+

This small suburb of Fairbanks is home to the University of Alaska Fairbanks, an international research center that also houses the Museum of the North. The college's proximity to Fairbanks puts it near a number of cultural amenities, like Pioneer Park, which commemorates Alaskan history.

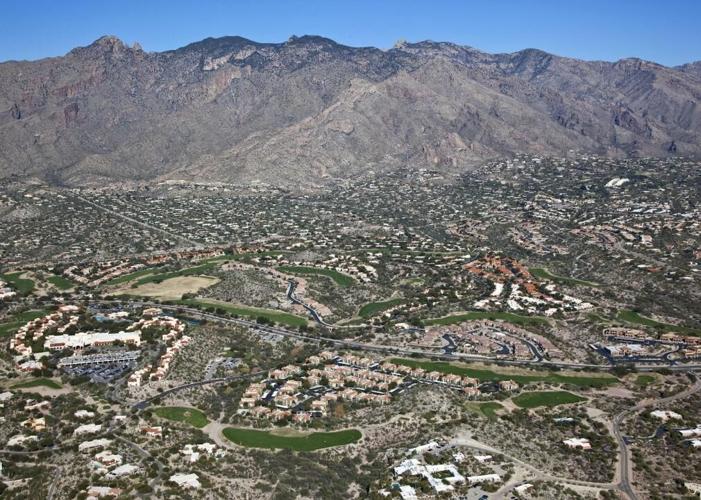

Arizona: Catalina Foothills

- Population: 51,756

- Location: Suburb of Tucson, AZ

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A

The affluent town of Catalina Foothills is less than 15 minutes from Tucson and is surrounded by the picturesque Santa Catalina Mountains. The town enjoys easy access to the luxury outdoor shopping center La Encantada, resorts, and museums. Nearby, the University of Arizona has a notable presence, including its operation of Biosphere 2.

Arkansas: Bentonville

- Population: 56,326

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Bentonville is the home of the first Walmart and now serves as the corporation's headquarters and the site of the Walmart Museum. It also houses the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art and is conveniently located near the Northwest Arkansas National Airport.

California: Santa Monica

- Population: 91,535

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Instantly recognizable by its iconic pier and Ferris wheel, Santa Monica provides coastal living that blends the outdoors with the arts. The city is renowned for its gorgeous beach, believed to be the birthplace of two-person beach volleyball. Public art abounds, with over 170 murals and a city-owned collection that rotates through public facilities.

Colorado: Holly Hills

- Population: 2,652

- Location: Suburb of Denver, CO

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

The quiet Denver suburb of Holly Hills offers modest home prices, good schools, and a friendly neighborhood vibe just 15 minutes from downtown Denver. This proximity gives residents access to as much or as little hubbub as they like, with cultural events, outdoor activities, restaurants, and educational centers galore.

Connecticut: West Hartford

- Population: 63,809

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Aficionados of fall foliage can find some of nature's best colors along the shores of the West Hartford Reservoirs. Even outside of the fall months, this city is becoming a favorite place to live thanks to its farmers' markets, museums, and historic sites. The University of Hartford and the University of Saint Joseph both have campuses in town.

Delaware: Hockessin

- Population: 13,608

- Location: Suburb in Delaware

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A

This Pennsylvania border town ranks as the best suburb to live in Delaware, in part due to its quiet way of life and proximity to both Philadelphia and Wilmington. Residents can enjoy the area's native flora at Mt. Cuba Center, a local botanic garden. The town's library has several book clubs, craft swaps, and a pen pal program.

Florida: Westchase

- Population: 24,818

- Location: Suburb of Tampa, FL

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A

Situated just outside of Tampa, Westchase residents enjoy easy access to city amenities and the beautiful beaches of St. Petersburg and Clearwater. A master-planned community, Westchase has plenty of amenities to keep locals occupied, including two parks, a public golf club, and swim and tennis centers.

Georgia: Johns Creek

- Population: 82,115

- Location: Suburb of Atlanta, GA

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Located 25 miles northeast of Atlanta, Johns Creek is an affluent suburb that's considered one of Georgia's safest cities. Currently under construction, the 192-acre Johns Creek Town Center development aims to transform a local business park into a town center with shops, homes, and a new park. Johns Creek also has a 1% for Art Program to encourage public art installations throughout the city.

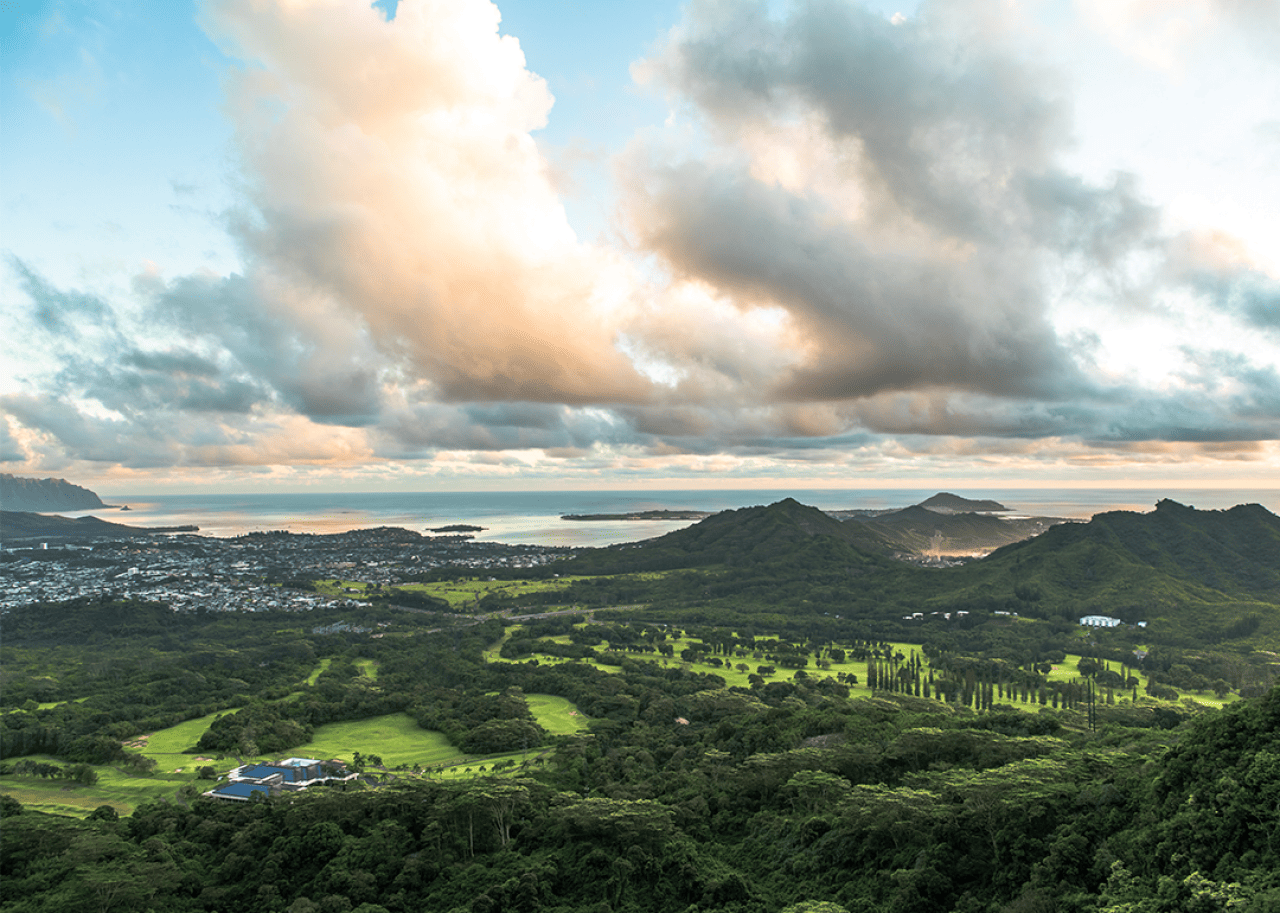

Hawai'i: Maunawili

- Population: 2,288

- Location: Suburb of Honolulu, HI

- Overall Niche grade: A-

- Public School grade: B+

Situated on the island of Oahu, just a few miles from the state capital of Honolulu, Maunawili is packed with the stunning vistas and outdoor adventures that the island is famous for. While the famous Maunawili Falls trail is currently closed for improvements, hikers can still take advantage of the Maunawili Trail.

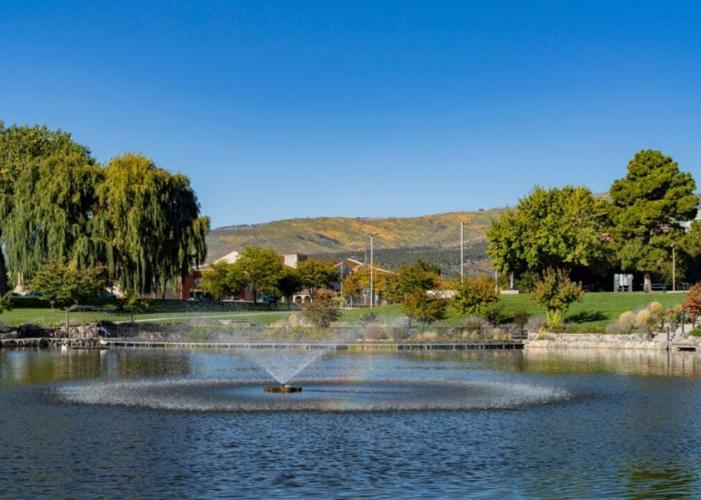

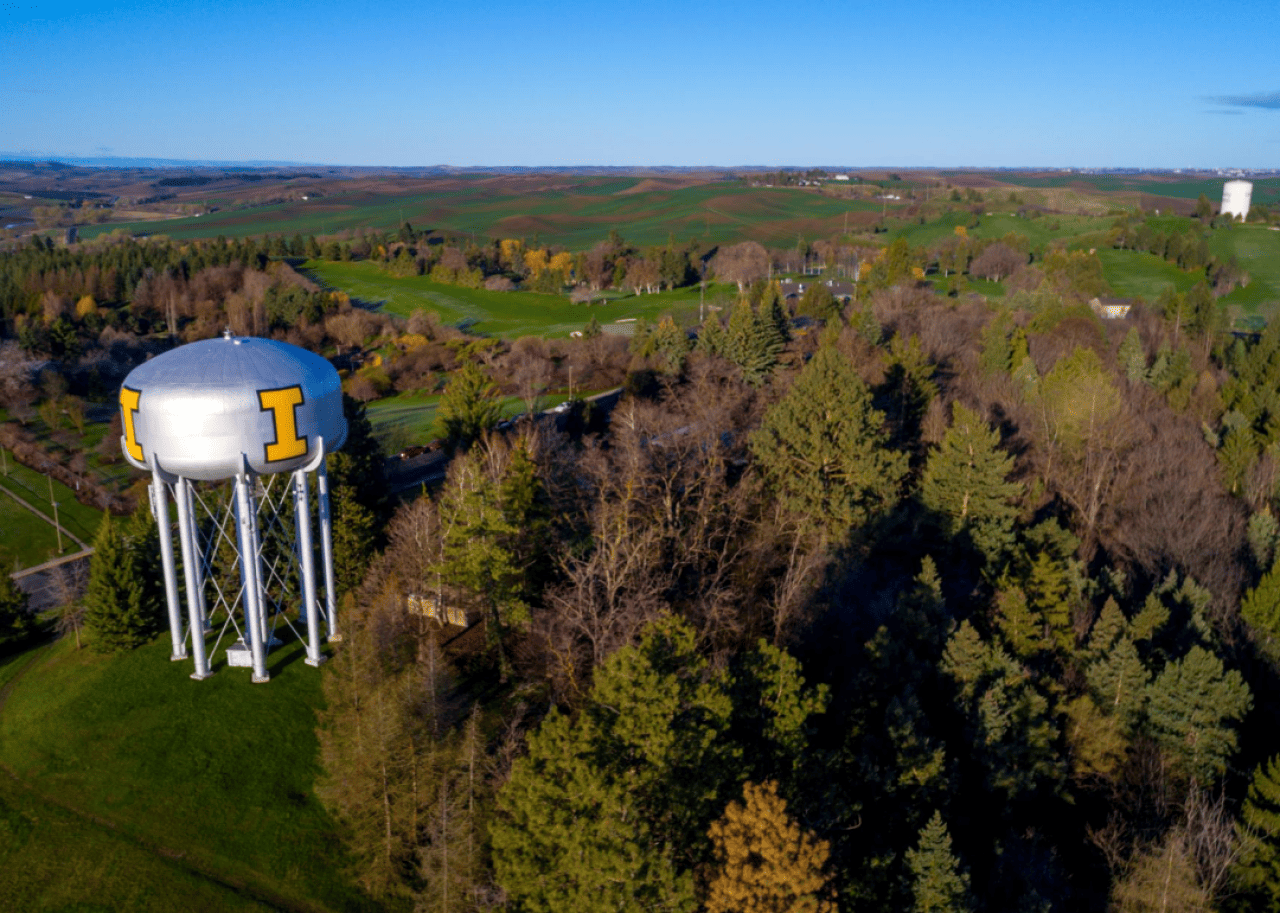

Idaho: Moscow

- Population: 25,868

- Overall Niche grade: A

- Public School grade: A

Moscow shares a border with Washington state and began attracting settlers around 1871 for its lush grasslands and large amount of timber. The town is home to a weekend farmers' market, the University of Idaho, and the paved Latah Trail, which connects Moscow and Troy for joggers and cyclists.

Illinois: Naperville

- Population: 149,424

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

One of Chicago's far western suburbs, Naperville is a family-friendly city with an acclaimed library system and the DuPage Children's Museum. The city's numerous parks feature a riverwalk, two golf courses, a swimming quarry, and a trap shooting range. Naperville's government provides fiscal transparency through its Open Checkbook initiative, which allows residents to see all city payments and vendors.

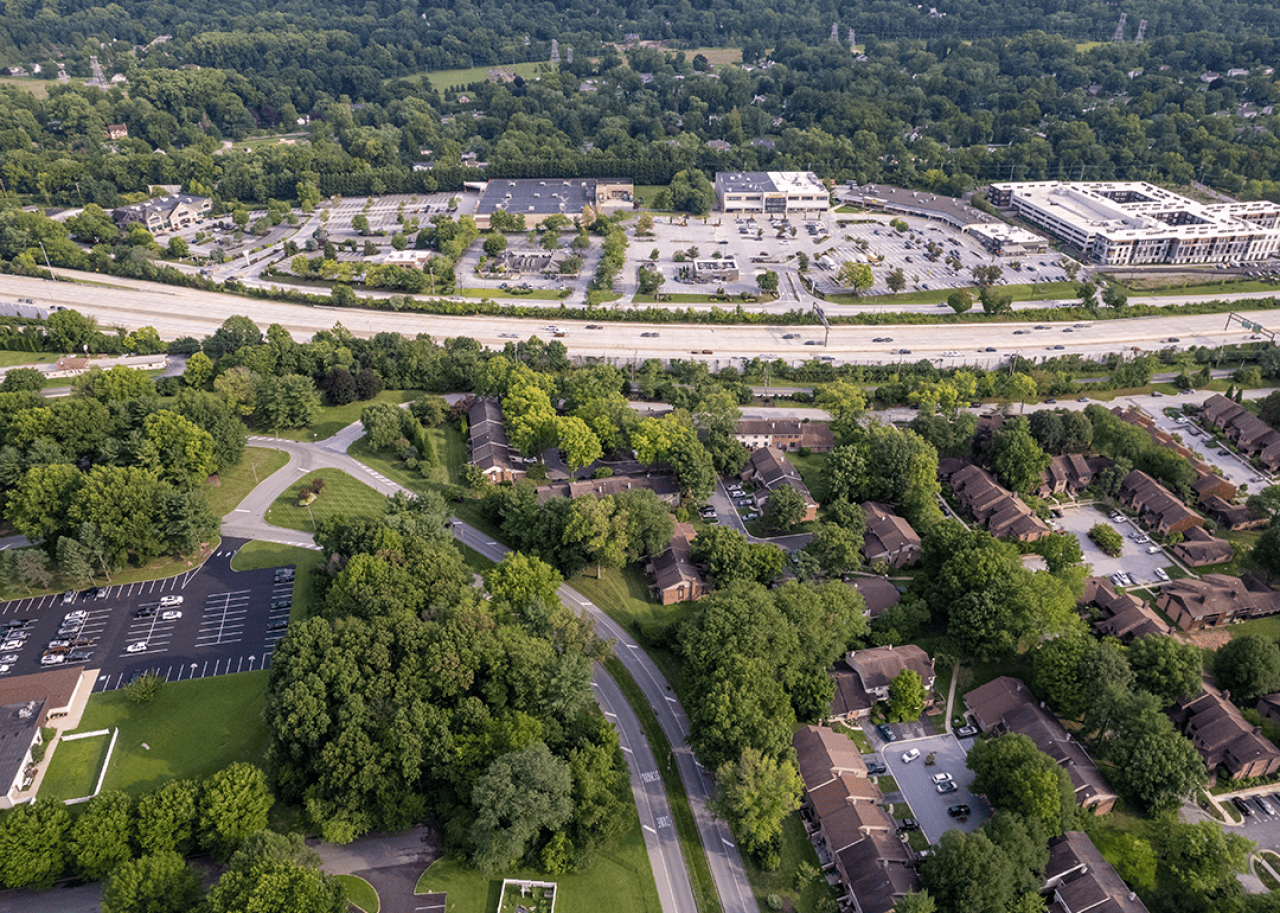

Indiana: Carmel

- Population: 100,501

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Located just outside of Indianapolis, Carmel is known for its safe neighborhoods and an annual Christmas market. The Japanese Garden is a favored attraction among locals.

Iowa: University Heights

- Population: 1,232

- Location: Suburb of Cedar Rapids, IA

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A

University Heights is situated just outside the University of Iowa campus. It's close to Kinnick Stadium, making it easy for locals to catch a Hawkeyes game.

Kansas: Leawood

- Population: 33,844

- Location: Suburb in Kansas

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Leawood is one of the safest cities to live in around Kansas City. The city maintains its landscape and aesthetic through a local garden club and an arts council, which manage the area's attractions and host community events throughout the year.

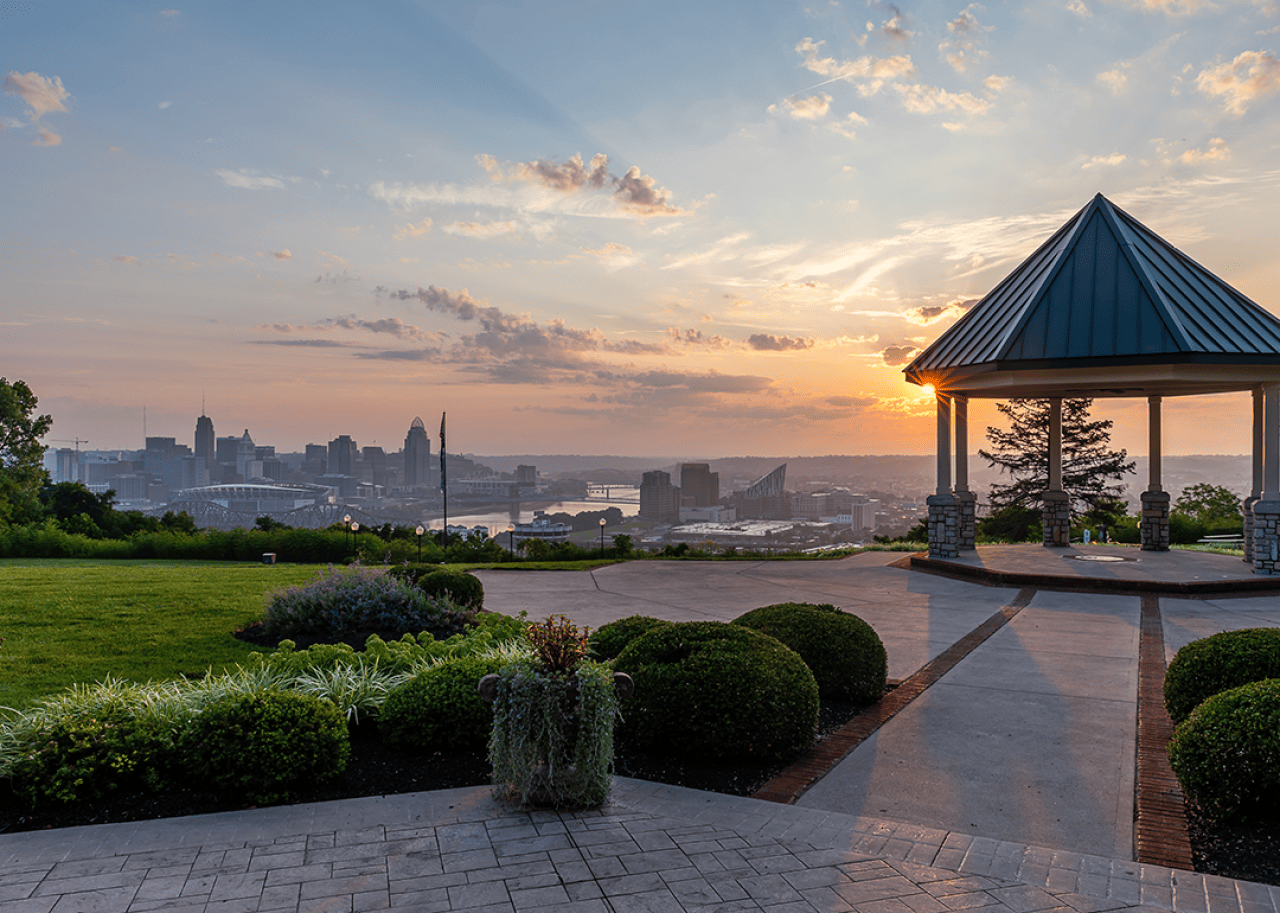

Kentucky: Park Hills

- Population: 3,155

- Location: Suburb in Kentucky

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A-

Part of the Cincinnati metro area, Park Hills is a small suburb that borders the 700-plus-acre Devou Park. The resident-driven Park Hills Civic Association produces many of the town's beloved annual events, including parades for Memorial Day and Halloween.

Louisiana: Prairieville

- Population: 35,010

- Location: Suburb of Baton Rouge, LA

- Overall Niche grade: A

- Public School grade: A

Located south of Baton Rouge, Prairieville is a quiet, unincorporated town in Ascension Parish. The town's residents skew younger, with nearly one-third of the population clocking in under age 18. Residents of this affluent town enjoy a weekly farmer's market year-round.

Maine: Cape Elizabeth

- Population: 9,547

- Location: Suburb in Maine

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

A suburb of the cool cultural hub of Portland, Cape Elizabeth is located on Casco Bay, an affluent Maine town known for the iconic Portland Head Light and Crescent Beach State Park.

Maryland: North Potomac

- Population: 23,994

- Location: Suburb in Maryland

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

North Potomac is a quiet suburb located about 20 miles northwest of Washington D.C. Part of the Muddy Branch Greenway Trail cuts through the town, providing opportunities for hiking, biking, and horseback riding. The town borders the Universities at Shady Grove, a Rockville campus featuring degree programs from nine of Maryland's public universities.

Massachusetts: Brookline

- Population: 62,822

- Location: Suburb of Boston, MA

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

John F. Kennedy spent his childhood in Brookline, and the area oozes history, like the fact that the Underground Railroad made important stops in Brookline that you can still visit. Today, community gardens and farmers' markets are just some of the amenities that make this Boston suburb a favored locale to raise a family.

Michigan: Okemos

- Population: 25,503

- Location: Suburb of Lansing, MI

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Okemos, located next to Michigan State University, has an abundance of youth sports activities, making the town an attractive place to raise a family. The Meridian Historical Village is another point of pride in the town. Comedian Seth Meyers attended elementary school in Okemos.

Minnesota: Falcon Heights

- Population: 5,145

- Location: Suburb of Minneapolis, MN

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A-

Every August, Falcon Heights welcomes visitors and locals alike to the Minnesota State Fair. This suburb, located between St. Paul and Minneapolis, is also home to the University of Minnesota St. Paul campus and its College of Food, Agricultural and Natural Resources Sciences.

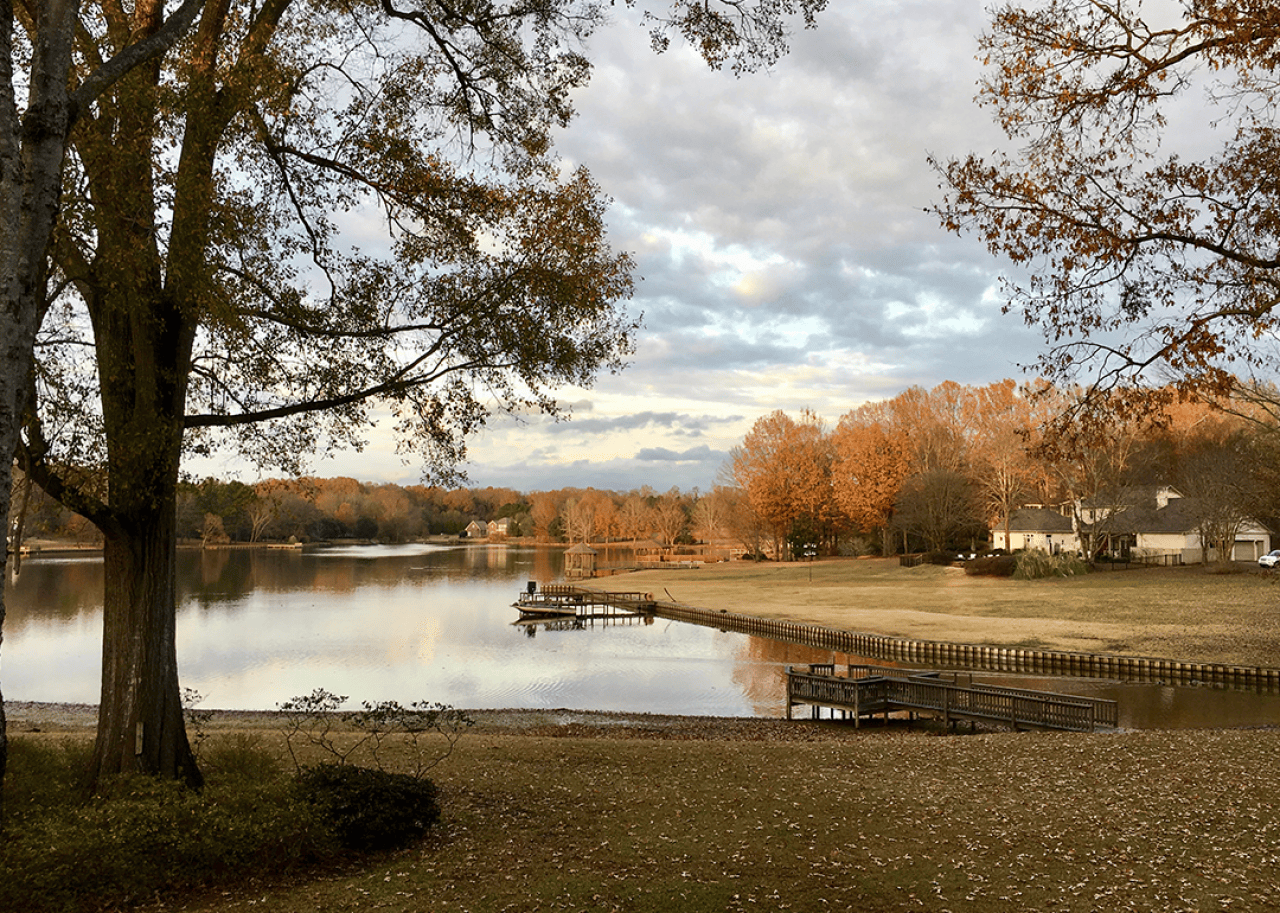

Mississippi: Madison

- Population: 27,775

- Location: Suburb of Jackson, MS

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Simmons Arboretum, Liberty Park, and Strawberry Patch Park are popular recreation sites in Madison. Although there are no college campuses in town, the local public schools are highly rated. Consequently, the populace tends to be well-educated, with 38% of residents holding a bachelor's degree and 28% having a master's or higher.

Missouri: Brentwood

- Population: 8,151

- Location: Suburb of St. Louis, MO

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

The "City of Warmth" is a western suburb of St. Louis that packs a lot into just two square miles. The Deer Creek Greenway, along the town's southern border, features a six-acre wetland arboretum. Two parks and connecting trails are along Black Creek, on the city's eastern border.

Montana: Bozeman

- Population: 55,042

- Overall Niche grade: A

- Public School grade: A

Bozeman is home to Montana State University, which has more than 17,000 enrolled students. Mountain ranges surround the city, where you can find attractions like the Museum of the Rockies. Bozeman Yellowstone International Airport is the busiest airport in Montana.

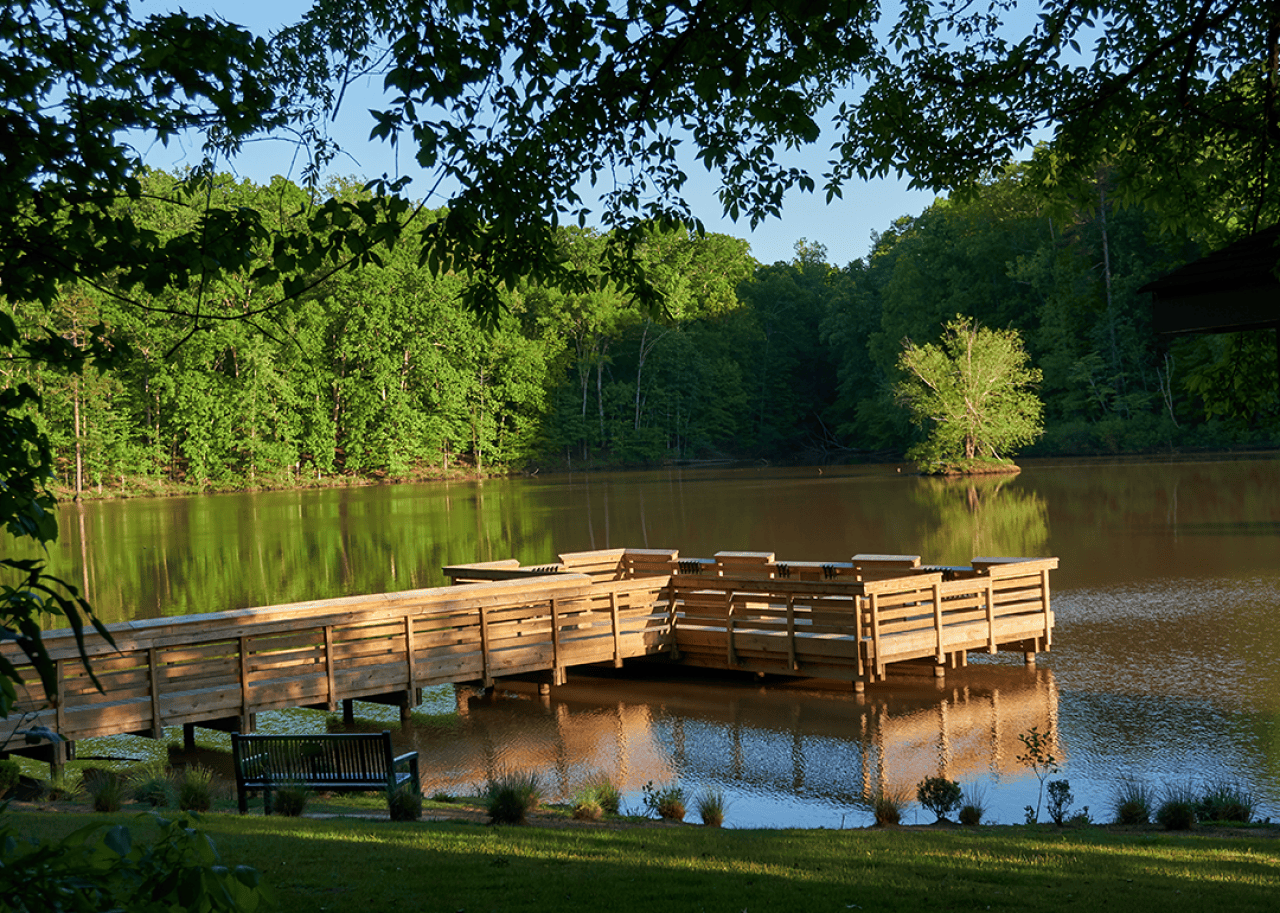

Nebraska: Papillion

- Population: 24,063

- Location: Suburb of Omaha, NE

- Overall Niche grade: A

- Public School grade: A-

Papillion is located about 15 miles outside of Omaha, and is best known for its bevy of recreational spaces. The Walnut Creek Lake and Recreation Area, for one, is a 450-acre park where locals and tourists can fish, hike, or camp.

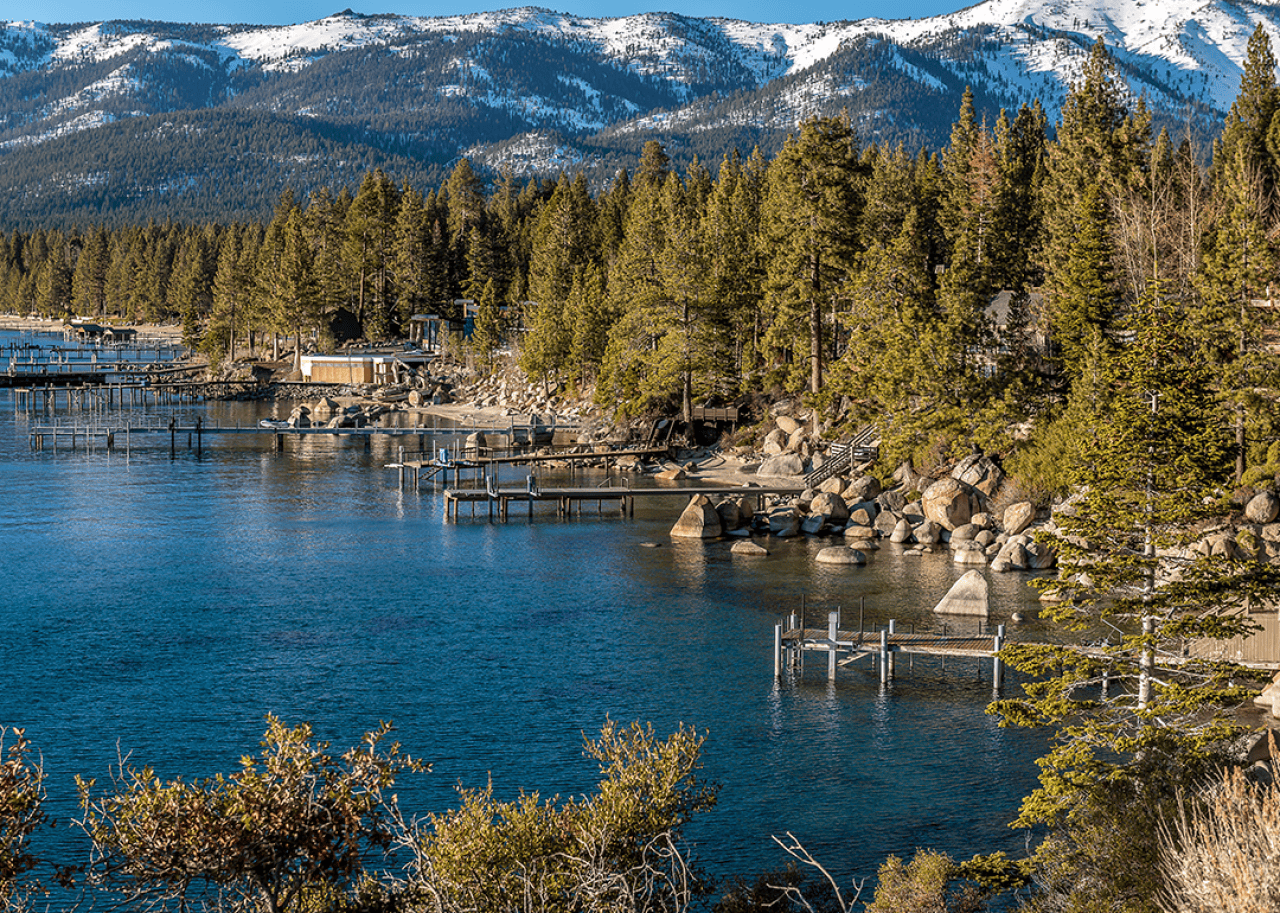

Nevada: Incline Village

- Population: 9,152

- Overall Niche grade: A

- Public School grade: A

Picturesque Incline Village offers four seasons of outdoor activities along the northeastern shore of Lake Tahoe. Golfers enjoy two popular golf courses, while water lovers flock to the lake. The surrounding Sierra Nevada mountains also offer fantastic skiing, mountain biking, and rock climbing.

New Hampshire: Hanover

- Population: 11,702

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Hanover is home to Dartmouth College, one of the oldest and most prestigious colleges in the country. This artsy college town has museums and cultural spots like the Hood Museum of Art and the Hopkins Center for the Arts. There are also ample opportunities to get outdoors in this rural area surrounded by the White Mountains and the Green Mountains.

New Jersey: Ho-Ho-Kus

- Population: 4,230

- Location: Suburb in New Jersey

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Located in Bergen County, about 25 miles from New York City, Ho-Ho-Kus is a historic suburb whose name has Native American origins. The borough promotes community service in many ways, including the opportunity to serve in the local Volunteer Ambulance Corps.

New Mexico: Los Alamos

- Population: 13,471

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Los Alamos is steeped in Native American history. Today, it's an outdoor-focused city with parks and public spaces, a bustling downtown, and a position as the "gateway" to three national parks and the Santa Fe National Forest. Bandelier National Monument offers a glimpse into the area's ancient past. There, visitors can climb wooden ladders to explore ancient cave dwellings inhabited by the region's earliest residents.

New York: Great Neck Plaza

- Population: 7,503

- Location: Suburb of New York City, NY

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

For being just one-third of a square mile, Long Island's Great Neck Plaza has a lot to offer. The village is centered around the Great Neck Plaza Business Improvement District, a hub with over 250 stores and restaurants located near the Long Island Rail Road's commuter train station. One of the village's more interesting jobs is that of Poetry Coordinator, a person in charge of Great Neck Plaza's poetry program and annual contest.

North Carolina: Cary

- Population: 176,686

- Location: Suburb of Raleigh, NC

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A

Every year, Cary hosts Spring Daze, an arts and crafts festival welcoming more than 170 local artists to Bond Park. The town is also known for being bike-friendly, thanks to its network of over 200 miles of greenways and on-road bike paths.

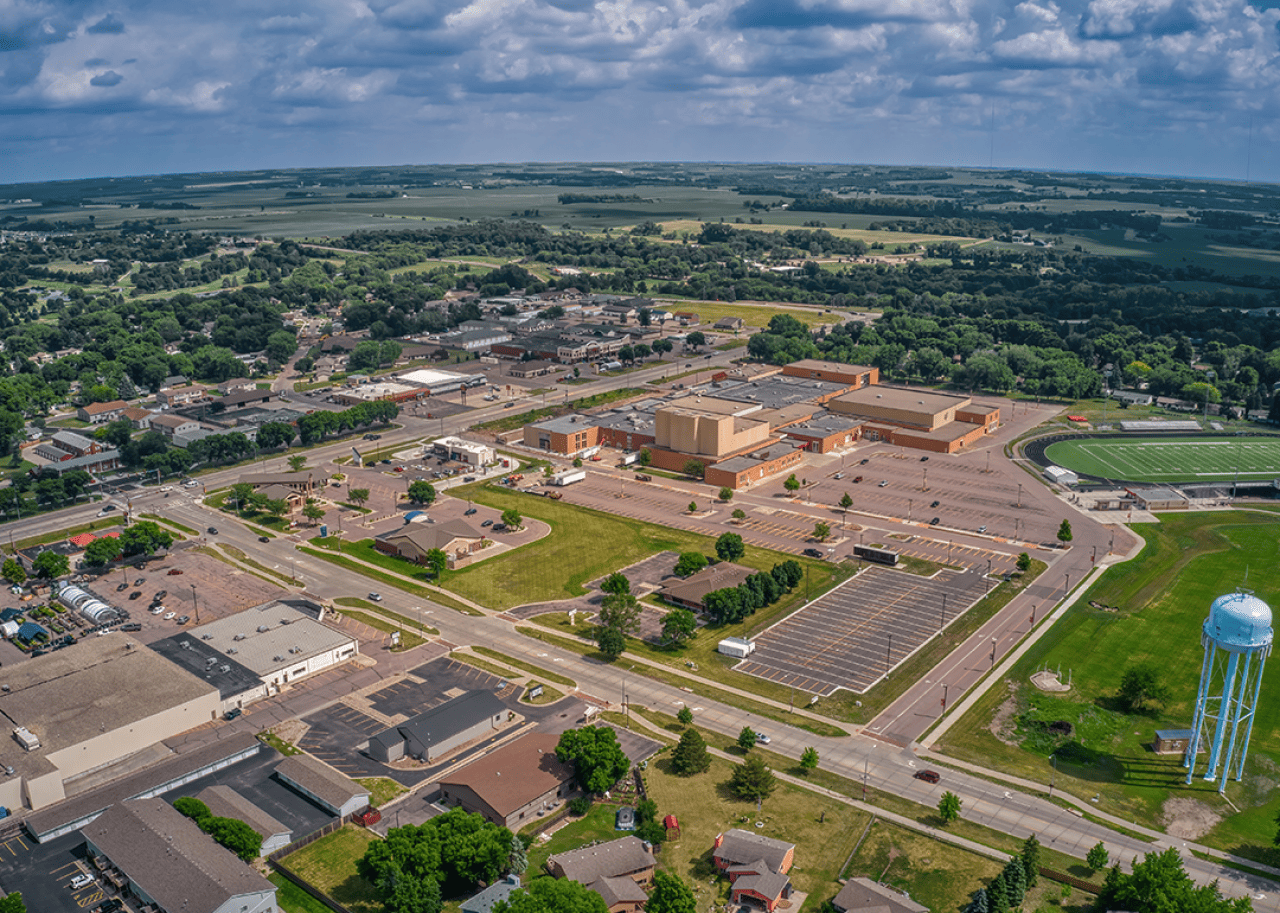

North Dakota: West Fargo

- Population: 39,325

- Location: Suburb of Fargo, ND

- Overall Niche grade: A

- Public School grade: B

West Fargo is one of the fastest-growing cities in North Dakota. To ensure West Fargo remains a great place to live as the town grows, the city has invested in a Neighborhood Revitalization Program to support local homeowners with loans for home improvement projects.

Ohio: Blue Ash

- Population: 13,374

- Location: Suburb of Cincinnati, OH

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

This dense suburb features Fortune 500 employers and a University of Cincinnati satellite campus. Summit Park, a 130-acre gem, plays host to Red, White, and Blue Ash, an annual Independence Day celebration that's considered one of the region's best. Crosley Field, a faithful reconstruction of the Cincinnati Reds' famed ballpark, hosts an annual vintage baseball game that takes spectators back to 1869.

Oklahoma: Edmond

- Population: 95,618

- Location: Suburb of Oklahoma City, OK

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Just minutes from Oklahoma City, Edmond is home to the University of Central Oklahoma and the Oklahoma University Medical Center among its higher-education institutions. Edmond has produced many star athletes, including Olympic gymnast Shannon Miller, NBA All-Star Blake Griffin, and Kansas basketball coach Bill Self.

Oregon: Bethany

- Population: 31,700

- Location: Suburb of Portland, OR

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Bethany, located near Portland, is one of the wealthiest small towns in the state. Bethany is also close to Beaverton, which is home to Nike and Oregon's Silicon Forest, one of the fastest-growing tech areas in the Pacific Northwest.

Pennsylvania: Chesterbrook

- Population: 5,439

- Location: Suburb of Philadelphia, PA

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Chesterbrook, a suburb of Philadelphia, lies just south of Valley Forge National Historical Park. The town boasts a small population, highly rated schools, a family-friendly atmosphere, and a diverse population.

Rhode Island: East Greenwich

- Population: 14,407

- Location: Suburb of Providence, RI

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Incorporated in 1677 and the birthplace of the country's first navy, East Greenwich is core to American history. This quaint New England town has a dense suburban layout along Greenwich Cove, which features a marina. Houses in the western part of the town are more spread out.

South Carolina: Tega Cay

- Population: 13,267

- Location: Suburb in South Carolina

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Tega Cay is a suburb of Charlotte, located right on the border between North and South Carolina. Its waterfront location on Lake Wylie makes Tega Cay a great choice for aquatic activities, but the city also offers plenty of parks and walking trails on land.

South Dakota: Brandon

- Population: 10,996

- Overall Niche grade: A

- Public School grade: A

Situated just east of Sioux Falls, Brandon offers easy access to Big Sioux Recreation Area, a state park where visitors can enjoy activities from canoeing to birdwatching. The park also hosts regular events, including a bike parade for the Fourth of July and a trick-or-treat trail for Halloween.

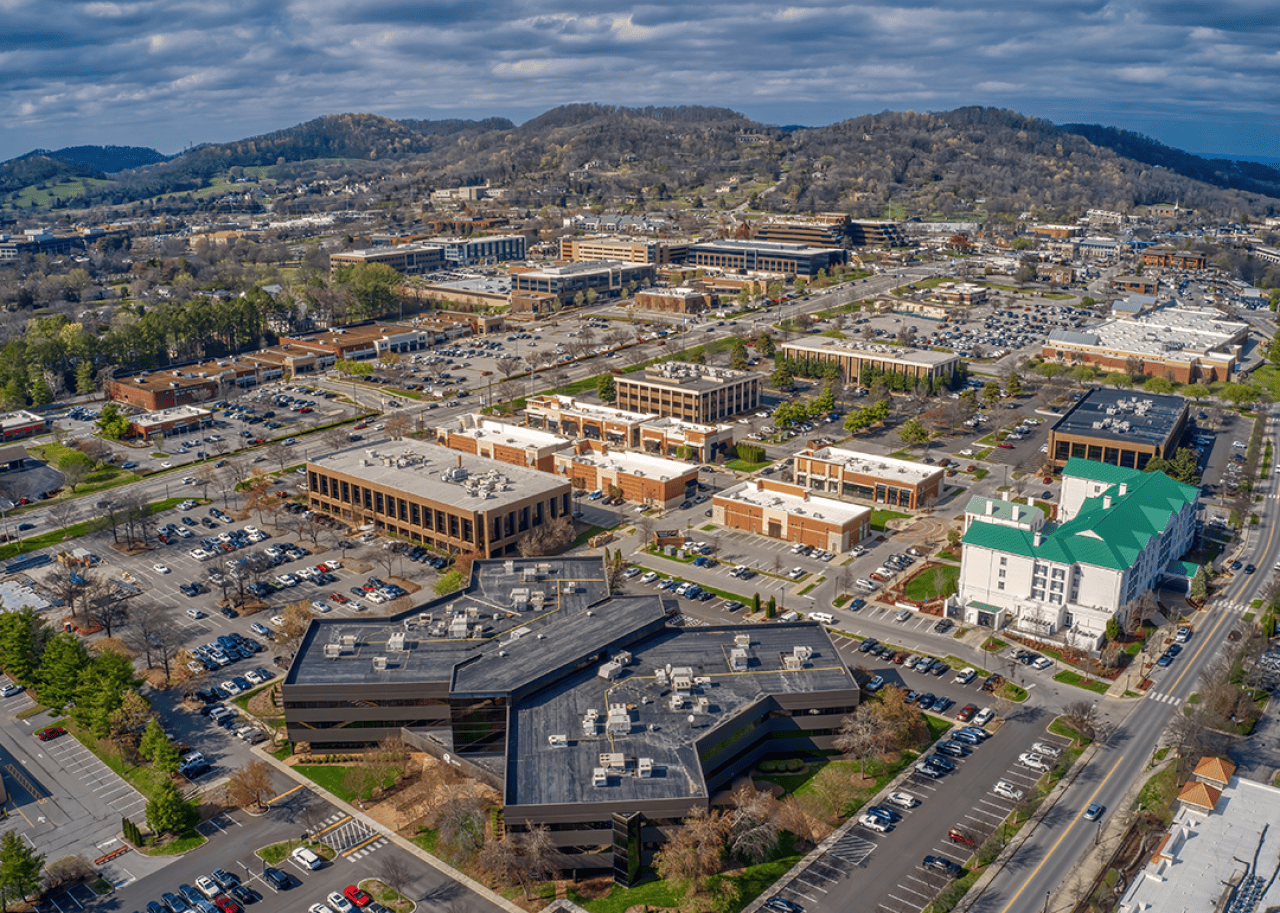

Tennessee: Nolensville

- Population: 14,545

- Location: Suburb of Nashville, TN

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

One of the country's fastest-growing cities, Nolensville's population increased by 137% between 2014 and 2023. The local government is experiencing some growing pains as it expands services for all those new residents, but Nolensville has still managed to keep a small-town feel and the lowest violent crime rate in the state.

Texas: Cinco Ranch

- Population: 19,139

- Location: Suburb of Houston, TX

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Planned communities around major Texas cities like Dallas and Houston are common. And, like many of them, Cinco Ranch has an abundance of pools, tennis courts, and golf courses. This Houston outpost has something more, though: an amateur radio society.

Utah: Park City

- Population: 8,365

- Overall Niche grade: A

- Public School grade: A-

The beauty of the Wasatch Mountains draws many to this affluent ski town, which has the most expensive real estate in Utah. Residents can take advantage of the free public transportation system, which boasts several buses and a historic Main Street trolley. Present and future Olympians train at Utah Olympic Park, which will once again be an Olympic venue in 2034.

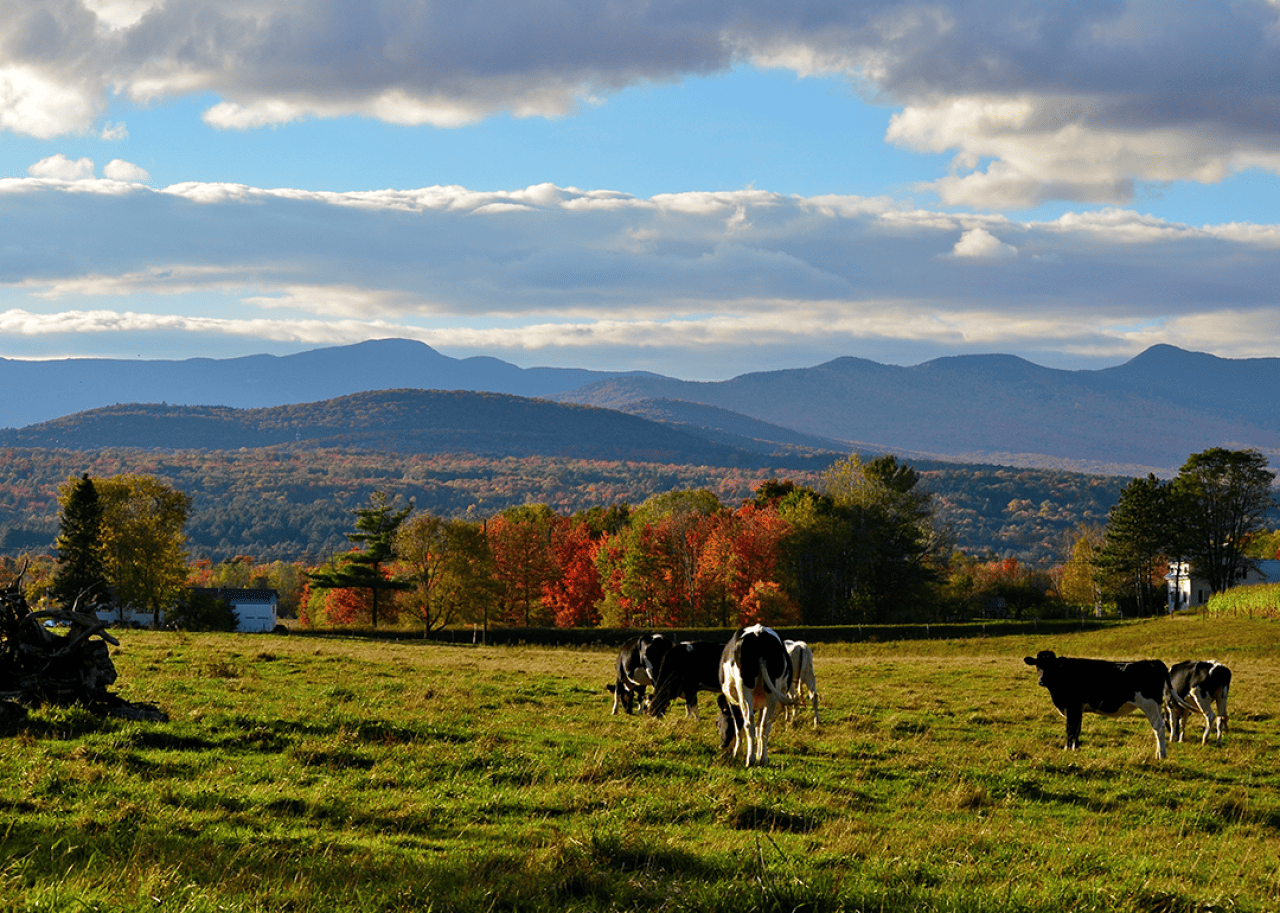

Vermont: South Burlington

- Population: 20,488

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A

From easy access to Lake Champlain to the Higher Ground music venue, South Burlington offers recreation for all kinds of people. The town is also home to Vermont's largest enclosed shopping mall, University Mall, making South Burlington a great destination for shoppers.

Virginia: Innsbrook

- Population: 8,559

- Location: Suburb of Richmond, VA

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A

Just outside the capital of Richmond, Innsbrook is a town best known for its mixed-use office and living spaces. Combining headquarters for startups and larger companies with plentiful retail and dining options, the community aims to make it easier to live and work in one cohesive area.

Washington: Redmond

- Population: 75,721

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Once a logging and agricultural town, Redmond now attracts many high-tech companies, including Microsoft and Nintendo of America. Residents have many opportunities to enjoy the great outdoors at the city's 47 parks, 59 miles of public trails, and Lake Sammamish. The city's parks and recreation department also has an Inclusion Services program for those experiencing a disability, and the local government is developing a plan that will make parks and trails accessible to all.

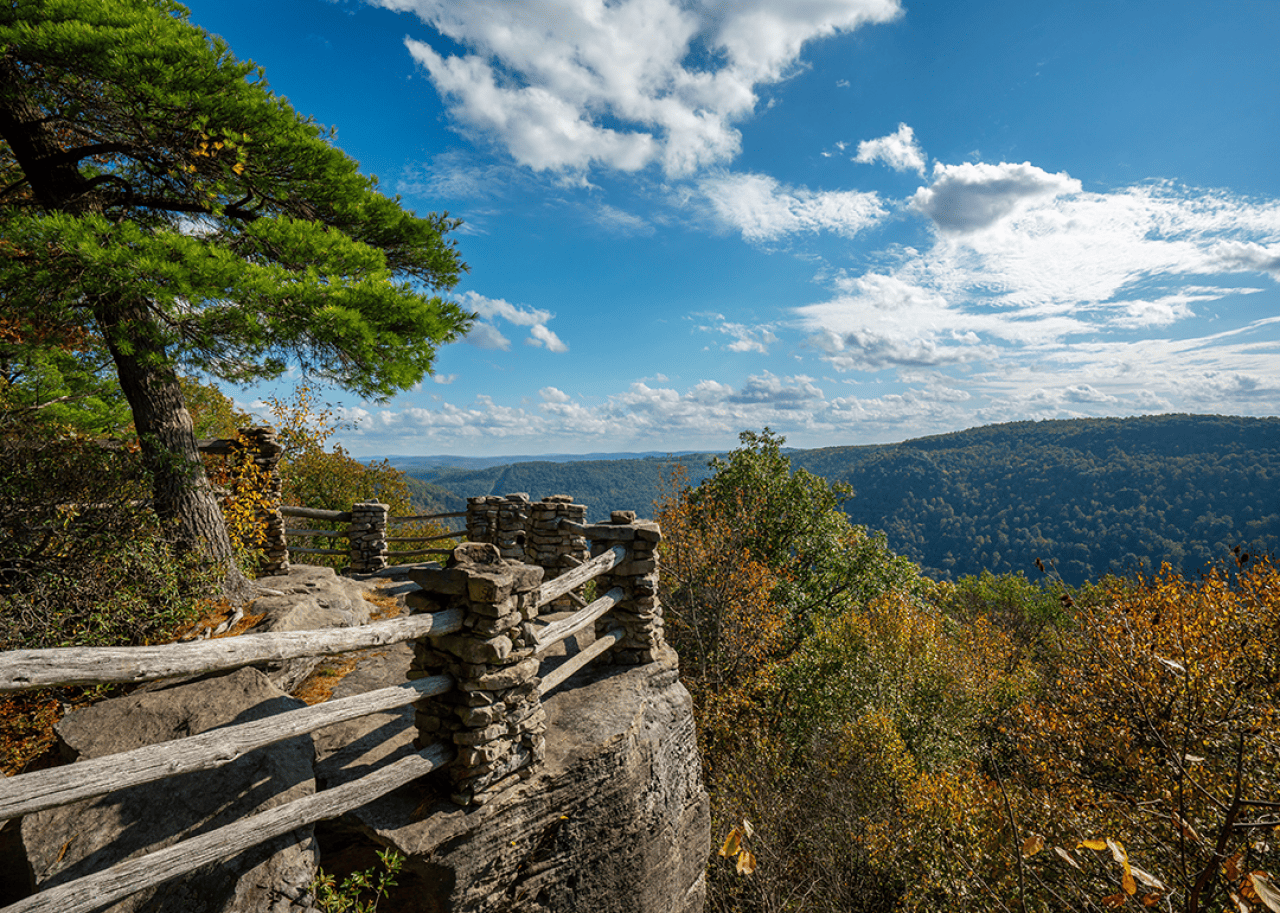

West Virginia: Star City

- Population: 1,894

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A

Founded in the early 20th century, Star City is a small town overlooking the Monongahela River. The city boasts the Edith Barill Riverfront Park, which has biking and walking trails and a public boat ramp for easy access to the river. The Caperton Trail follows the river to Morgantown and passes the West Virginia University Arboretum.

Wisconsin: Kohler

- Population: 2,136

- Overall Niche grade: A+

- Public School grade: A+

Home to Destination Kohler, a five-star resort that has hosted six major golf championships and the Ryder Cup, Kohler also has plenty of activities for its locals. For instance, consider visiting the Bookworm Gardens, a botanical garden that hosts events based on popular children's books.

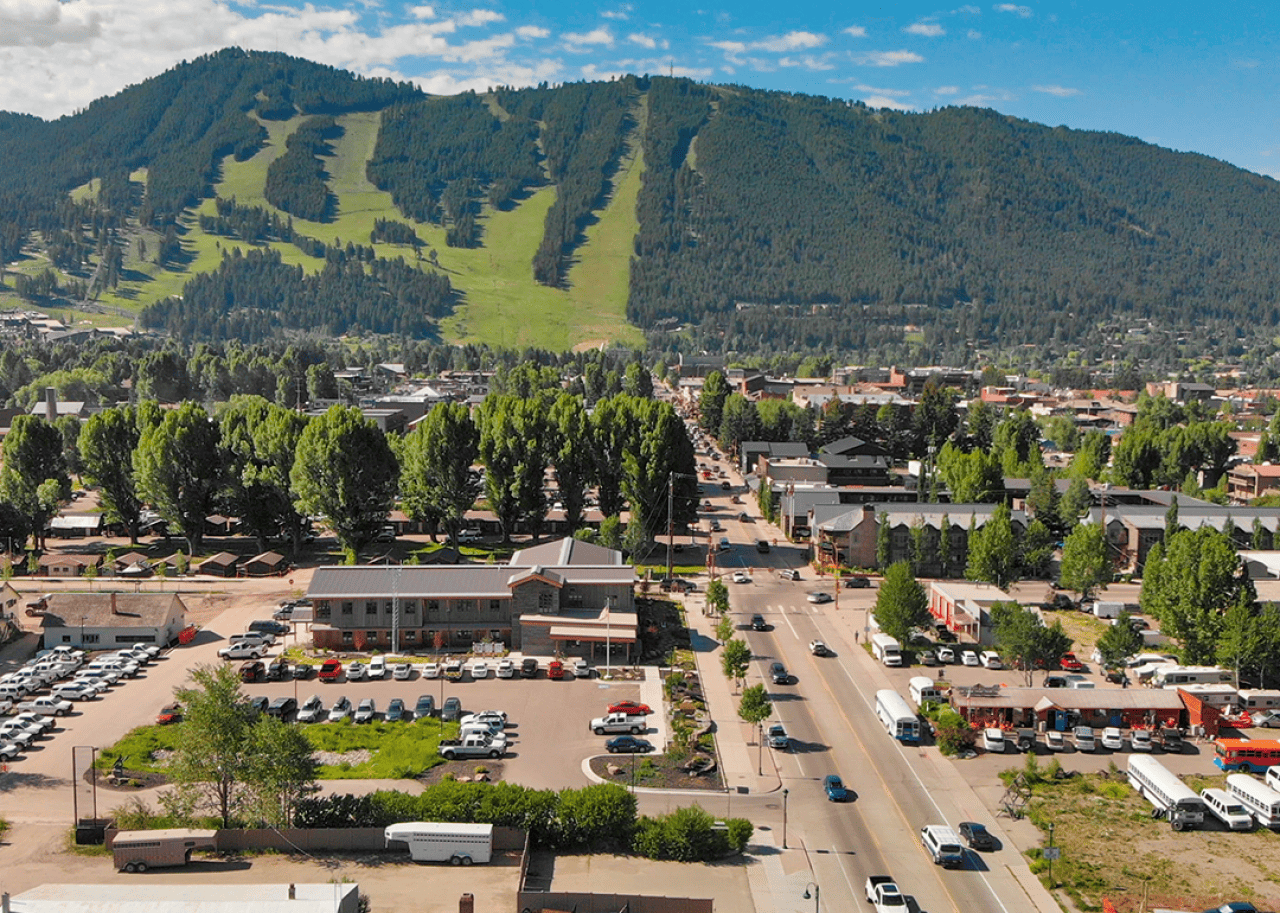

Wyoming: Jackson

- Population: 10,746

- Overall Niche grade: A

- Public School grade: A-

Jackson is a wonder of natural beauty: To the north are Grand Teton National Park and Yellowstone National Park, and to the south is Bridger-Teton National Forest. But you don't have to be outdoorsy to love the town. Jackson has a dense suburban feel, with lots of restaurants and a local arts scene.

Data reporting by Rob Powell. Story editing by Cu Fleshman. Copy editing by Meg Shields.

What do you look for in an ideal town? Proximity to trails, lakes, and beaches? How about top-ranked schools for your children? Would you like a professional or college sports team nearby, or do you prefer museums and art walks?

Stacker compiled a list of the best places to live in every state using Niche’s 2020 rankings. Niche ranks places to live based on many factors, including the cost of living, educational attainment, housing, and public schools.

Many cities on the list are suburbs experiencing growth thanks to rapid improvements in their metropolitan areas, whether it’s the creation of new rail systems or a megacorporation moving in. Other entries include planned communities or older cities that have been revamped with grassroots efforts focusing on greener ways of living, drawing in new businesses, or increased devotion to the arts. Towns with large colleges regularly appear, as prestigious universities employ thousands of workers and provide diverse recreational and educational offerings for families.

Each slide includes the city’s population, median home value, median rent, and median household income. More details on Niche’s methodology can be found here. Whether you’re thinking of relocation or are big on hometown pride, click through to find the best place to live in every state.

You may also like: Best places to raise a family in the Midwest