David Mehl would like you to know one thing about a life filled with great accomplishment, tolerable failure and incredible tragedy: Jesus Christ, his lord and saviour, saw him through.

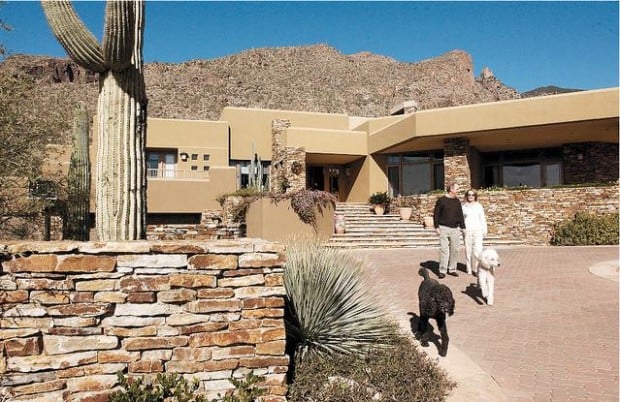

Mehl sits atop the world these days. The front range of the Santa Catalina Mountains rises up from the back yard of his home high in the Foothills.

Cottonwood Properties, the company he founded with his brother George, owns five miles of Tortolita mountain-front at Dove Mountain in Marana. There, two-acre lots in the foothills are going for up to $1.2 million and selling so well that he's about to raise prices.

He skis from his vacation home on the slopes at Telluride, Colo., or takes his two sons helicopter-skiing in the Canadian Rockies. He fly-fishes with his business partner above the Arctic Circle in Russia. He's met the president.

Over the years, though, the valleys have been deeper than the peaks were high. The last time he made this big an imprint on the geography of his adopted home was more than 20 years ago when he and George broke the residential zoning in the Catalina Foothills and built the resort hotel, golf course, homes and businesses at La Paloma.

Their company lost money on the deal. George and David nearly wiped out the riches they had amassed over the previous decade.

As the Mehl brothers were climbing back from that financial slide, their life was shattered in a manner that no real-estate debacle could ever approach in its awfulness.

On March 29, 1991, David, his wife, Bonnie, and their two children, Wesley and Carson, waited in Telluride with his sister Martha Dornette and her family for George to arrive with his wife and three daughters. They planned to spend the Easter weekend playing in the snow and checking on the progress of the family vacation house they were building on the scenic town's ski slopes.

The day had dawned clear in Tucson, but it was snowing heavily in Colorado. The Telluride airport has a short runway, on a 9,078-foot-high mesa surrounded by mountains that tower above 14,000 feet.

"When they didn't land, at first you don't think much of it, but then when a number of hours went by, we started worrying. We called the terminal in Tucson and found out they had left on time, and that's when we got very fearful."

The family began calling Colorado authorities. A sheriff's deputy brought the news that the plane had crashed while trying a lower-altitude landing at nearby Cortez.

In low visibility, George had twice attempted an instrument landing then slammed into a cliff at 7,700 feet. George, 41, his wife, Debbie, 41, and their three little girls, Natalie, 12, Laura, 8, and Jenna, 3, were all killed.

"You really do feel like your life has ended, too," said David. "I just got really angry and depressed. Some days I was angry at George, I was angry at myself and, frankly, I don't remember much of that first year after the accident. It was like living through a fog.

"I didn't know what to say to my kids. I had no answers to give them. That's what struck me so strongly at the time. You know, they're asking ‘Why?' and "How?' and I'm wanting to help them deal with their grief and I didn't have anything to say. I had nothing undergirding me for the first time in my life because I'd always been the control person and the detail person, and I had nothing to offer and that was scary."

Bonnie Mehl, who said she had been raised as "a strong Christian," had her faith to console her. That made things better, but by no means easy. She loved George as well and had become close friends with Debbie. They watched each other's children, vacationed together. "I've just never had a better ski partner," she said.

"I don't think you ever grieve easily, but there's hope, there's a great hope because you know where they are," said Bonnie. "The grief is that they're gone from your present life, and it's so unbelievably painful that at times it's just hard to get through a day and you think that, in the worst of it, you think it's not going to be any different, it's not going to be better until you get on the other side. But it gradually gets better. It gradually gets less painful and there are things that help you along the way - for me, long walks and listening to music. Other people need to be around people. Scripture really helped me a lot."

Bonnie and David worried about the boys. Wesley, 12, had lost his best friend, George's daughter Natalie. It was a little easier for Carson, only 8 at the time, but he, too, was good friends with his cousin Laura, and he was living with a family that had lost its joy.

Moving on

"We needed help as a family to move on," said Bonnie. They sought out a counselor who told them to stop living out a prolonged funeral.

"It seems so easy now to recognize, but when you're hurt you can't see that. She just really helped us look at the big picture, that we could be able to laugh together again and see that we were going to make it through this."

Bonnie continued to pray for David's conversion because she knew it would give him hope, not because she saw anything lacking in his character.

"When I say I prayed for David, it wasn't like I was praying over him. He knew, but I never pressured him. I believe that things happen in God's timing. I was called to be obedient to God. I wasn't called to drag my husband into the kingdom."

Jesus was no help to David Mehl in 1991. He stayed angry.

He would not find peace until March 1995, when he sat by a memorial to his brother's family at George Mehl Family Park along River Road and gave himself over to a faith that George had accepted 20 years before.

It wasn't the first time David Mehl (pronounced "meal") had reluctantly followed in his big brother's footsteps.

When Jonah Mehl, a successful plastics manufacturer in Cincinnati, told his two sons to go West, George came to Tucson on a University of Arizona tennis scholarship in 1967. Two years later, David had his sights set on Stanford, but despite good grades, excellent SAT scores and tennis skills nearly comparable to George's, he was turned down. He became a member of the Wildcat tennis team as his second choice.

He pledged a different fraternity. He and George were friends, but he didn't think they should be joined at the hip. They followed different paths in their academic life. David studied political science, aiming at a life as a university professor. He grew a beard, wore his hair shoulder-length.

George began a construction business while still in college and was busily buying, fixing and selling properties when David left Tucson in May 1973 for graduate school at the University of Illinois.

Bonnie followed when they married the following January. The couple had first met at a high school dance in Cincinnati, but the romance began when both were undergraduates. Bonnie had moved to Phoenix to attend Arizona State University. David visited, they fell in love and she transferred to the UA after one semester.

David earned a master's degree at Illinois but decided his writing skills were not good enough for the "publish or perish" world of the Ph.D. scene. He and Bonnie missed Tucson, and it was easy for George to lure them back.

George had started small while still in college - buying old homes on North Fourth Avenue, living in garages or guest houses out back, rehabbing and rezoning the homes for conversion to business use in the burgeoning hippie commercial district.

George's interests were varied. He studied Eastern religions as well as economics, became enamored of Zen Buddhism. "He used to cook all his own macrobiotic food," said David.

"He traveled with a set of pots and pans," said Bonnie. "He was impulsive then."

When George came home from a weekend camping trip and announced that he had become a Christian, David said he wasn't surprised. "I was surprised that, 10 years later, he was still a Christian."

Brothers and partners

The brothers' first project together was a small apartment complex on North Oracle Road near Amphitheater High School. Bonnie and David lived in an apartment nearby. Their subsequent moves mirrored the success of the fledgling company. When they bought a two-story office building on East Grant Road and rented the ground floor to the Hogan School of Real Estate, David and Bonnie moved into one of two second-floor apartments. "That was a real step up. It had a washer and dryer," David said.

In addition to his partnership with George, David ran his own property-management business. His contracts included some run-down "trailer courts, in the worst possible sense of that term." Bonnie, who had earned a master's degree in social work, went to work for the Tucson Unified School District.

The Mehls bought a couple of hotels very unlike the Westin they would later build at La Paloma. One of them was the Thunderbird, 2637 N. Oracle Road, which sheltered prostitutes, drug addicts and some folks a step away from homelessness. They spiffed it up and sold it twice, but each time the new owners failed to make their payments.

The third time, they just gave it away to Teen Challenge for use as a drug and alcohol treatment center. It's still there.

At first, their father was their principal investor. "Dad staked us a little bit to get started. We delivered. He was shocked at how well he did," said David.

When their dreams grew larger, Dad balked at financing them. The Mehls rounded up new investors and began building larger apartment complexes and shopping centers. They formed their own cable television company, the first in Tucson, to serve their apartment complexes.

George became the youngest president of the Southern Arizona Home Builders Association, did a stint as finance chairman of the Pima County Republican Party, raised money for candidates and ran campaigns. He also raised money to combat famine in Mozambique and for cancer research, taught Sunday school, coached soccer, headed up the 88-CRIME board and We The People, flew helicopters and airplanes.

"He was a force of nature," said friend Greg Lunn, who became a state senator and a Pima County supervisor with George's help. "He had a tremendous energy which carried everyone along with him. He accomplished a tremendous amount in a very short period of time."

David had the political science degree, but George did most of the political glad-handing. George had a degree in economics and finance, but David kept the closest eye on the books. The sum of the Mehl brothers proved greater than the parts.

When George built a "spec" house near North Swan and East River roads, Bonnie and David decided to buy it - their first move toward the Foothills.

Aiming higher

They wanted to build apartments in the Foothills, on some land that the Murphey Trust had held onto for decades.

The Mehls' Cottonwood Properties wanted just a small piece of virgin Foothills that legendary Tucson developer John Murphey had bought for a relative pittance back in the day. When the Murphey Trust didn't want to split it up, the Mehls made an offer for the entire 790 acres.

It was a long shot. The area was zoned for one home per acre, and the neighboring residents were legendarily protective of their views and privacy. It would take political juice and public-relations finesse just to rezone the land. It would take millions to plan it and tens of millions more to buy it and develop it.

"It was a time when we were full of ourselves," David recently said in a luncheon speech to a group of Christian business people. "We thought we could do anything, and apparently the bankers thought so, too. It was amazing how much money we borrowed."

"La Paloma was a huge leap, in most ways sort of crazy," said David.

But the Mehl brothers had been raised to dream big, he said. His father and grandfather had made and lost fortunes several times. "And my mother (Marge) is one of the world's great optimists. George and I grew up in a family where we were encouraged to dream and put dreams into action."

"A huge leap"

Take a look at photographs of the two "wonder boys" at 31 and 33, the ages they were when they bought the La Paloma parcel in 1983: David smiles; George grins. There were times, David said, when he and George would leave a room full of bankers and lawyers, find a private spot and just laugh out loud.

It took all they had, all they could borrow - and more. The hard-fought rezoning helped end the political careers of the three Pima County supervisors who voted for it - Katie Dusenberry, E.S. "Bud" Walker and Conrad Joyner. Residents petitioned to overturn the rezoning, and it took a state Supreme Court decision to clear the way.

Things got "very ugly and personal," said David.

"That was an emotional period," said Bonnie. "It wasn't the most wanted development in the Foothills. We were so young - it would be easier to handle it now."

David Yetman was a Pima County supervisor then, one of two "no" votes on the La Paloma rezoning. George Mehl knew he didn't have Yetman's vote, but he continued to visit his office. He was polite and honest, Yetman said.

"George was the public face. One of the things he tried to sell me on was there was a golf course designed by Jack Nicklaus, but I didn't care who designed a golf course that shouldn't be there in the first place. That turning of super-fine desert into water-consuming turf made no sense to me.

"For what they were doing, they did a very good job, but it was a job that belonged elsewhere," said Yetman.

The developer as demon

It's the quintessential Tucson argument, the one that paints neighbors as selfish NIMBYs, environmentalists as wackos and politicians as either no-growthers or puppets of developers. The developers are, of course, demons.

"Developer is the only nine-letter, four-letter word I know," said Tucson developer Stan Abrams.

"It's very easy to sit in a situation in which you have a job and, unless the world comes apart, you're gonna be there," Abrams said. "It's a tougher situation to be at risk, and the world is driven by people willing to take risks."

La Paloma was a nearly fatal risk for Cottonwood Properties.

The hotel and the golf course cost millions more to build than planned. The contractor for the hotel, L.G. Leffler, stopped paying his subcontractors in the middle of the project, later to file for bankruptcy. The bonding company that insured completion refused to pay off. Southwest Savings & Loan, which loaned $47.2 million to the project, was later shut down. The Resolution Trust Corporation charged a $19 million loss to the La Paloma deal.

The Mehls sold off all their shopping centers and apartment complexes to pour money into keeping the deal going. David warned Bonnie that they were likely to lose the home they had just purchased on the golf course at La Paloma.

The brothers had one last strategy. The Mehls owned 2,600 acres in the Tortolita Mountains. They proposed a land swap for 3,339 acres of adjoining state land, bringing in Westinghouse Properties as a partner. If they could deliver the swap, Westinghouse would pay off the debt on the 34 acres of office property adjoining La Paloma that the state would accept in trade for the Tortolita property. They would be able to keep their interest in the hotel they had built.

But the land swap had attracted much negative attention. Environmentalists didn't want state land in the Tortolitas falling into the hands of developers. Critics questioned the relative values of the two parcels. Gov. Bruce Babbitt, a Democrat and one of three members of the state Land Selection Board, publicly opposed the swap. Attorney General Bob Corbin and Treasurer Ray Rottas, both Republicans, had been allied with the Mehls in political campaigns, but Corbin was wavering.

On Aug. 19, 1986, the night before the state land board was to vote on it, the Mehl brothers were certain the vote would go against them. "I remember hugging each other and I said, ‘I wouldn't trade a minute of it and if you want to do it all again, I'm your partner,' " said David.

The swap was approved after Corbin extracted some face-saving concessions on the amount of land the Mehls would receive. They ended up with about 3,000 acres.

"Fortunately, the hotel was a success and Westin bought it. We had a three-year period of absolute financial misery until we sold the hotel. We had no partners, that was dumb, but I think what we developed was spectacular," said David.

"In '89, we owned nothing, owed nothing, then we won the settlement from the bonding company, so in '90-'91-'92, we had capital." Property was cheap after the real-estate meltdown of the late ‘80s. They bought 2,000 apartment units and began looking at Rita Ranch, a stalled housing development on the Southeast Side.

George, who taught adult Sunday school at Grace Chapel, decided at that time to make a large cash gift to his church.

"I was always the guardian, even though George was older," David said to the luncheon audience. "I said ‘Do the math, George. We haven't made a profit.'

"George said, ‘You know, David, yesterday I had nothing. I will share what I have today.' "

That was George: generous, optimistic and more than a bit impetuous. His death at age 41 and the loss of his entire family was almost more than his brother could bear.

Surviving tragedy

David made it through the year following his brother's death in March 1991 by doing what he does best and doing it so well on auto-pilot that he recouped his company's losses of the previous decade.

"It was in that next year I bought the land at Rita Ranch and actually made some of the best purchases and best business decisions I've ever made," David said.

The development game operates on a variation of the "buy low, sell high" principle of all good businesses. At its simplest level, you buy land, you improve its value by rezoning it and providing infrastructure, then either sell it for a profit or build something on it that produces income.

David Mehl prefers a more creative approach. "I like to figure out what people would buy, what you can do that will make people want to live here and pay a premium for it." When they drive in to one of his developments, he said, "people know it feels better, but they don't know the five things you did that create that feeling."

At Dove Mountain, you turn off a ragged two-lane county road onto Dove Mountain Boulevard, four smooth lanes with a median that curves through preserved or replanted desert. There are walking paths. Cottonwood limits builders to one-story construction, requires premium roofing tiles and desert hues on exterior paint. Its custom lots are behind rusted iron gates with mountain silhouettes.

At Rita Ranch, it was almost too easy. The Resolution Trust Corporation was unloading land that defunct Pima Savings had been stuck with in the real-estate meltdown of the late '80s.

"Land was selling for 30 cents on the dollar or better," said Stan Abrams. Abrams said RTC officials knew they could get better prices if they held on to the land, but felt pressured by Congress to end the S&L scandal's reverberations by liquidating the seized property.

In June 1992, Cottonwood paid $2.9 million for 630 acres in the Southeast Side development just as the housing market on that side of town was heating back up. The land was already rezoned for homes and commercial activity; 106 lots had roads, power and utilities; four homes were already built. The company bought another 60 acres nearby.

"The Lord has a sense of humor," said David. "All the time and effort we spent at La Paloma, and I'm really proud of it, but we lost money and then the market crashed. I made back my net worth at Rita Ranch with none of my heart and soul in it."

A den of Christians

His heart had been crushed; his soul was about to come under siege.

David always knew that becoming a Christian would greatly please his wife and his brother, but he didn't want to turn his back on his heritage. His mother was Methodist, but his father and his grandfather, who had fled Lithuania as a 14-year-old orphan, were Jewish. "I grew up confused," he said.

After George's death, he fell into a den of Christians. As executor of his brother's estate, he was now a one-third partner in two Christian radio stations.

One partner was Tom Regina, a successful manufacturer of windows and doors and an influential member of Tucson's evangelical community.

George's funeral was the first time Regina ever set eyes on David. "He was standing there alone, greeting people, holding it together. He breaks my heart."

David's other new partner was Doug Martin, president and general manager of the stations. "I had never met him at all before. He wasn't interested in that part of George's life," Martin said.

When he met with David and his lawyer, Martin worried they would enforce an agreement that required the other partners to buy back shares if one dies. "He could have taken us out at the knees," Martin said. "We had just put the FM station on the air. We were losing money, bleeding red ink."

Martin told Mehl: "I think what's supposed to happen here, David, is that you're supposed to come on our board and you're gonna become a Christian."

It was half bluff, half hope, but it worked.

David joined the board, and eventually all three men donated their shares to the nonprofit corporation that now operates Good News Communications.

David began to seriously consider becoming a Christian. He concluded that his concerns about turning his back on his father weren't valid. "My dad was a strong-believing person. I certainly wasn't upholding any family tradition by not believing in anything."

But he also recognized the psychological factors at work on him. He didn't want to grasp at faith simply because he needed something to fill the awful void, simply because George believed.

So he conducted his due diligence. He read books on science and faith. He read the lives of the martyrs. He read the Bible, starting at Genesis. "It took me a couple years. If you actually read the Bible instead of listening to other people," he said, "it's absolutely astounding how clear the message is."

He and Regina began meeting weekly at Millie's Pancake Haus to discuss what he had read.

Regina said David approached Christianity the same way he approaches business deals. "He's pragmatic. He'll want to test. He gathers his facts. He isn't content with knowing 50 percent; he's got to know it all."

Bonnie continued to pray, and she switched churches so she could bring David to services with a more evangelical flavor at Catalina Foothills Church, a member of the evangelical Presbyterian Church in America.

David continued to read. "It was in March of 1995, just four years after George's death, after doing a lot of studying and reading, that it just struck me that nobody would make up the things in the Bible. I was reading the word and recognizing that it was true." He picked up the phone.

David Mehl's conversion

Tom Regina remembers the moment. "He said ‘What do you do when you feel like you finally believe?' ‘Pray,' I said. ‘What?' he said, and ‘Where?' I told him ‘anywhere' and he said he was going to the memorial."

The memorial is set in a mesquite grove at the county's George Mehl Family Park on River Road. On a stuccoed wall faced with marble, a picture of George and his family is flanked by quotations from the Old and New Testament.

"Tom wanted to join me, and I was too prideful or too much of a private person to do that. I went by myself, and I sat down there. I was praying to the Lord and not to George, but that was a comfortable place for me to be.

"After I accepted Jesus Christ as my Lord and Saviour, things got very different," said David. "Suddenly, I had something to live for that was not me. I could never explain to the kids why evil things happen. and now I can.

"Now I have the certainty of seeing George again."

The fog lifts

He still thinks about his brother every day, but the fog has lifted from his busy life.

In 1996, when Westinghouse Corporation was falling apart, it spun off its real-estate division, and a Florida developer ended up with the big parcel at the foot of the Tortolita Mountains that George and David had assembled and lost while extricating themselves from debt at La Paloma.

Cottonwood Properties bought it back and is now embarked on a 20- to 30-year plan to develop 6,200 acres of rolling desert and canyons whose views rival what David and Bonnie see from their own back yard.

David renamed it from Red Hawk to Dove Mountain to echo George's naming of La Paloma. "He liked the symbolism of the Christian dove in the Foothills," David said.

Once again, it hasn't been easy.

The designation of his land as critical habitat for the endangered cactus ferruginous pygmy owl had a devastating effect. Cottonwood cut the planned density in half. David arranged an auction of nearby state land and made a deal with the town of Marana to lease it and designate it as a wildlife preserve. He would pay the yearly lease of about $475,000, and the state would recognize the preserve as "mitigation" for the development he planned on critical habitat.

Vistoso Partners, the development company of his Northwest rivals, Conley and Daryl Wolfswinkel, outbid the town at auction. Mehl had to fight them to a standstill in the Arizona Legislature to keep them from tailoring his deal to fit a hotel they wanted to build at Stone Canyon in their Rancho Vistoso development.

Last year, the Wolfswinkels relented and gave the land back to Marana. Cottonwood has its mitigation land but no hotel developer on the line. The owl's endangered status is in doubt from recent court decisions, but David says "delisting" probably wouldn't change his plans for Dove Mountain all that much.

He's learned a few things over the years. His debt ratio is low. He didn't build the expensive Gallery golf courses at Dove Mountain, instead selling the land to golf course developer John McMillan's Palo Verde Partners.

"That's one thing where you have to compliment David," said Conley Wolfswinkel. "He got rid of those golf courses. Golf courses and hotel deals, economically, they're just black holes," Wolfswinkel said.

They can be, said David, who says he's "fortunate to have found John McMillan." The hotel at La Paloma was a success, he said. He and George just weren't able to hang on to it. He wants to build a hotel at Dove Mountain.

"I don't know why in the world after the last experience, but I just like to build things," he said during that recent luncheon speech. "I started praying, ‘If I shouldn't do this, Lord, remove the opportunity.' In this case, He keeps removing the opportunity."

Cottonwood Properties had cut a deal with the Hyatt hotel chain and was ready to build a hotel in summer of 2001. Then came the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11 and a precipitous drop in tourism.

Life is good

The rest of Dove Mountain is on Cottonwood's timetable - 1,600 of the planned 6,000 homes have been built so far. About 150 of the custom-home lots at Canyon Pass and along the Gallery golf course have sold for $200,000 to $1.2 million. The two Gallery golf courses have won praise for developer McMillan. A sports center is on the way. A shopping center is planned.

Mehl's more important ventures are also going well.

Son Wesley, 24, is a UA graduate. He married last year and works for a property-appraisal firm. Carson, 21, is a senior at Pepperdine University, where he studies religion and is mastering the long board in the Malibu surf.

Bonnie and David, both 52, celebrated their 30th wedding anniversary on Jan. 5. Bonnie said her partnership with David has always been wonderful, and "our marriage is so much stronger now that he's a believer because now we can share things of the spirit."

The Good News radio stations are debt-free and offering a steady diet of conservative commentary on KVOI (690-AM) and inspirational messages on KGMS (940-AM).

About six years ago, Bonnie and David began praying for guidance on how to repay the community for all the blessings they had received, something that would combine their love of their adopted town with their faith. They decided what Tucson really needed was a place to train the region's future Christian leaders. They got together with other members of the Catalina Foothills Church, and the Pusch Ridge Christian Academy was born.

David is president of its school board.

It has an enrollment of 385 and plans for up to 1,200 middle and high school students.

"The beauty of David," said Principal Eric Abrams, "is that he does understand the power of having a vision, and, with a single-minded determination, working toward that vision, to act and to speak as if you've already achieved it.

"He never seems to be down, never seems to be discouraged," said Abrams.

Not anymore.

These days, David Mehl begins his day with God before moving to the gym in his home to keep those ski legs in shape. "If you get up in the morning and read the Bible and pray, it's amazing how well the rest of the day goes."

He and Bonnie gather regularly with friends such as Tom Regina and his wife to pray and read the Bible. He said it's not as serious as it sounds. "The concept that if you're a Christian you need to be dour is so untrue it's just ridiculous," said David.

"We really enjoy life," he said. "We enjoy our family. We enjoy our friends. We laugh a lot. We drink some wine. It's really not that stodgy.

"We are the most joyful of people," said Bonnie.

"We have a future," said David. "We should be happy."

Contact reporter Tom Beal at 573-4158 or tombeal@azstarnet.com