Joe Pinella remembers that horrific day in June 1991.

He remembers driving on I-40 outside of Flagstaff, his Bronco pulling his Ferrari as he headed to New Jersey to celebrate his birthday with friends.

He remembers the trailer hitch coming undone and smashing into his car and pushing it down a ravine. He remembers flying through the windshield.

He remembers the EMT who had been riding in the truck behind him rushing down that ravine and asking him if he could move. His neck was broken; his head had shifted about three inches over his shoulder. He couldn’t move.

“Call Flight for Life,” the EMT shouted. “We have a quad here.”

Pinella, then a semiretired entrepreneur with plans for an active life, was indeed a quadriplegic. Two vertebrae had shattered into 150 pieces. Four discs in his spine were gone; the rest were herniated. It was an injury similar to the one that crippled the late actor Christopher Reeve.

“He had a devastating injury,” said Dr. Donald Hales, the neck specialist who happened to be on duty at the Flagstaff Medical Center that June day.

Pinella was told that he would spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair. He needed to learn to accept that. He couldn’t.

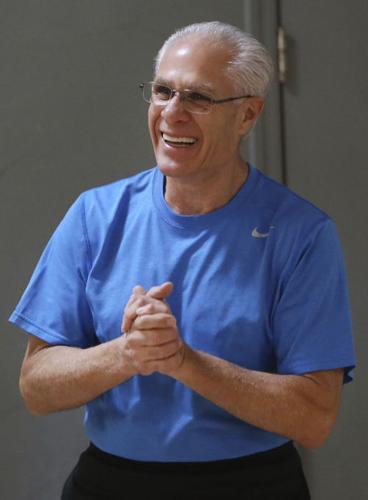

Today, Pinella, 66 and an Oro Valley resident, walks without any aid, stands straight and without pain, takes no medications, and teaches tai chi and qigong five times a week.

This weekend he will perform in Dancing in the Street’s “The Nutcracker Ballet” — something he has done for four years.

This is the story of how Joe Pinella learned to walk again, to brush his teeth, eat on his own, and live an active life free of wheelchairs, walkers, a cane, or even medications.

“I CAN’T MOVE”

“There were a whole list of little miracles that day,” Pinella said on a recent Monday shortly before he was to teach a tai chi class.

“The EMT in the truck behind me, the helicopter was close and I was at the hospital within 30 minutes, and the resident that day was a neck specialist.”

Even with that fast, good attention, Pinella wasn’t expected to make it through intact.

He knows this because as the doctors furiously scrambled to save him, he found himself floating above them, watching as they worked on him, listening as they talked.

“I heard the doctor say ‘This is about saving his life; he’s going to be a quad,’” said Pinella, who had owned a body shop specializing in Ferraris.

“I saw the tools they used on me — they were using Craftsman, and I wondered why they weren’t using Snap-ons, which are the best. There was the nurse who wouldn’t leave at the end of her shift because she was still tweezing glass out of me.’”

Pinella is a bit uncomfortable talking about the experience. “It sounds so New Agey,” he said.

But it happened — Hales was incredulous when Pinella was able to relay back to him what was said and done.

And that experience was at the root of his determination to get back to his old self.

“That’s what gave me the confidence,” Pinella said.

“I had this knowing; I knew my spinal cord would be OK.”

After spending about a month in the Flagstaff hospital, Pinella was sent home to Scottsdale, confined to a wheelchair and prescribed physical therapy.

“Having that knowing that I would be OK, I thought physical therapy would help me do that,” he said.

At that point, Pinella could do nothing for himself. He had no control over his hands or his legs. He wore a neck-to-waist brace 24/7. He went to physical therapy with the goal of eventually caring for himself, walking free of any aids.

“But their whole attitude was to make me accept that I would have to live the way I was,” said Pinella.

Depression and frustration spent plenty of time with Pinella — not unusual with those who have his kinds of injuries, said Hales from his Flagstaff office.

He had constant care. He needed someone to bathe him, brush his teeth, feed him.

“It would have been easy to still be in a wheelchair,” said Pinella, now sitting on the carpeted floor of his Oro Valley living room, his shoes off and his hands gracefully punctuating his words.

“I was on a concoction of medicines. I couldn’t eat, wash, care for myself.”

He often questioned his resolve.

“I would get convinced I was nuts. I’m missing bones, pieces. I’d look at the science and say, ‘Nah, not gonna happen.’ There was constant conflict.”

After about eight weeks of physical therapy, Pinella quit in disgust that their goal was not the same as his: to walk and care for himself again.

“We were at war,” he said of he and his physical therapist.

In despair, he reached back to his teen years, when he had studied tai chi and qigong with a master in New York. He called him and, through a Chinese interpreter, asked advice.

He told Pinella to do qigong, an ancient Chinese practice that is intended to put the breath, body and mind in alignment.

“You don’t understand,” Pinella told him. “I can’t move.”

“Imagine you are doing the exercise,” Pinella said, quoting his teacher. “Get in a warm swimming pool and imagine you are in the womb. Imagine your body rebuilding itself. Get anatomy books and ask the doctor to point out where you have injuries, and imagine those parts are healing. Imagine the energy going around the blocks in your body.”

“It felt like a game plan,” said Pinella. “If I do nothing, nothing changes.”

He spent three hours every morning and three every afternoon visualizing while sitting in a hot tub.

“I did everything with my eyes shut,” he said. “I imagined my arms moving. I was doing that all the time. I visualized I was eating, visualized breathing exercises, moving my legs. There were several months of doing that.”

He rarely opened his eyes when he was in the hot tub because he didn’t want to break his concentration.

“I wanted to feel the movement,” he said. “It took a long time before I started looking.”

Once, after about eight months of the exercises, he allowed himself one of those peeks. This time, it wasn’t in his head — his hands really were moving.

“When I was able to control my hands, I knew it would work,” he said.

It wasn’t a fast recovery from there. Pinella had to learn the most basic things all over. But slowly he regained the use of his body. He continued the exercises on a daily basis.

After about seven years, Pinella was back to the way he was, with the exception of two fingers on his left hand — he can’t move them.

His surgeon in Flagstaff, Dr. Hales, admits that Pinella’s case is unusual.

“When people come in and are quads from neck injuries, it’s not common that they can make a recovery,” he said. “It’s remarkable when someone can make a recovery. … Joe had a devastating injury and I would not have expected the kind of recovery he got. Maybe walking with crutches, maybe. But to be teaching tai chi like he is? That’s quite remarkable.”

But Hales is not surprised that Pinella was able to do it.

“It’s a testament to his motivation and his attitude that pushed him through all the hard times after the injury,” he said. “We don’t have the science behind it, but we know that those that can keep a positive attitude can heal better. It somehow improves healing.”

“There are times where I go ‘holy s---’,” said Pinella. “But I don’t dwell on it. I forget about it. It was a horrible thing, but I look at the outcome.”

That outcome includes teaching tai chi and qigong — the slow, gentle exercises that brought him back to health — to about 2,000 people a year, mostly seniors. It is not unusual for his students to come back to him and marvel at how their arthritis no longer prevents them from squatting or turning their necks.

“I don’t want anybody to think I do anything,” Pinella said about his grateful students.

“I didn’t make this stuff (exercise) up. It’s thousands of years old. All we try to do is set the body up. The doctor doesn’t heal wounds, the body does that. The exercise gives the body a chance.”

As for his own astonishing recovery, he credits those exercises.

And one other thing:

“I never gave up.”