When Brenda Vargas made an almost off-handed comment to her boss that she hoped to own a home someday, she had no idea how close she was at the time.

The widowed mother of five, a custodian at the University of Arizona Campus Recreation Center, was directed to Habitat for Humanity by her supervisor and the next thing she knew she was picking up a hammer and hanging drywall alongside other volunteers in Habitat’s Women Build program.

This Saturday, about a year after first contacting the organization, Vargas and her family will be handed the keys to the four-bedroom home she and her daughter, Lillian, 16, helped build. Habitat for Humanity Tucson is celebrating National Women Build Week and will cap the week on Saturday with the dedication of the Vargas home and the raising of the walls for two more houses in the neighborhood near South Park Avenue and East Drexel Road.

“It’s unreal. I still can’t believe it,” Vargas said last week at the Habitat for Humanity offices as she prepared to sign the contract that will make her a homeowner.

The home is the 15th built in Tucson in the Women Build program as Habitat approaches 400 homes built in the Tucson area since 1980. Women Build got its start in 1991 in North Carolina when a group of volunteers formed an all-female construction crew to build a Habitat house.

The idea gained momentum until it was made an official Habitat for Humanity International initiative in 1998. A year later, crews of women volunteers were building Habitat homes in Tucson.

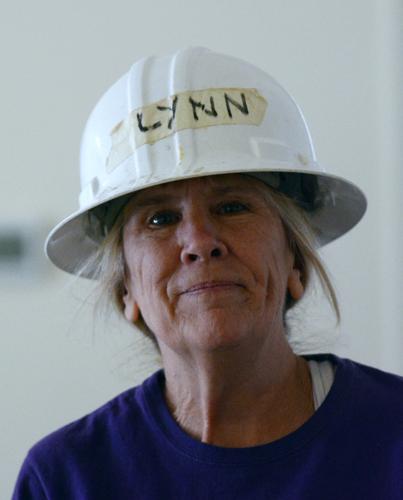

Lynn Andreen, a crew leader and one of the many volunteers who was involved in the construction of the Vargas home, said that on top of the feeling of satisfaction she gets from the community work she’s doing, the opportunity to be a part of a construction crew keeps her volunteering three days a week at Habitat sites.

Andreen, a former bookkeeper and former owner of a day care, said volunteers get the chance to get into every aspect of construction, some of which comes with some adventure for Andreen, who grew up in a house where girls didn’t get to do what the men did.

“When I was growing up, my dad was kind of old-fashioned so I couldn’t get into any of the tools or anything,” Andreen said. “I came out and they taught me and let me do anything. We get in there and do the heavy duty stuff, which I think is great.

“I’ve done framing. I’ve done landscaping. They let me drive the tractor. My dad has lawn equipment, but I never got to do that. The smile on my face when I was driving that tractor … they were taking pictures. They just had no idea how great that was.”

Even though the labor is cheap, the quality of construction doesn’t take a back seat to what is available on the market, said T. VanHook, who first volunteered for Habitat in 2003 and was named CEO two years ago. In fact, she said, in some aspects of construction Habitat homes go beyond what is standard in a home built in a commercial subdivision.

“The better constructed and the more energy-efficient the house, the lower the cost to the resident over the long term,” VanHook said, explaining the organization’s rationale for adding certain amenities.

The Vargas home and the others in the neighborhood come with the latest energy-efficient technology in lighting and windows. There are epoxy floors throughout, widely considered one of the most durable flooring treatments.

“We caulk and seal all of the baseboards, which not all builders do, because we want the house to be as energy-efficient as possible,” VanHook said.

While no one in the Vargas family is disabled, the home is built with the anticipation that disabled access might be needed by a future owner. The home is adaptable to standards in the Americans with Disabilities Act, VanHook said, which would make it relatively easy to make it full-on ADA accessible.

“ADA adaptation as people age is one of the expenses that forces people out of their homes across the country,” VanHook said.

Doorways are wider than is standard to accommodate a wheel chair for a visitor or a future resident. One of the two bathrooms has a roll-in shower.

Habitat’s thinking, VanHook said, is that buying a home through Habitat for Humanity is a path for the Vargas family and other Habitat homeowners toward the purchase of another home, and the added amenities, particularly those for disabled residents, might be needed by a future owner and add value to the home.

Mortgage payments are based on a number of factors, but on average run about $700 per month over 20 to 25 years.

“We want to make sure families can build equity,” she said. “We’re helping them build family wealth. We’re helping them get education for their children. The idea is that they’re able to eventually buy houses on the commercial market and move up.”

One of the other extra features of the Habitat home is the one-car garage, something that VanHook said is somewhat controversial “because it’s not basic shelter.”

“But no other builder in Arizona is building a house without a garage,” VanHook said. “For us it’s about ending the cycle of poverty, so why would we build something no other commercial builder is building? We want Habitat neighborhoods to be like other commercial neighborhoods.”

Andreen said when she got involved building homes for Habitat, the quality of the homes was one of the first things she noticed.

“We have a house that we rent out in Florida and when I go through it, I go, ‘Oh my gosh,’” she said. “I go up in the attic and there are nails sticking through. You go look here and it’s solid and you know it’s efficient.”

Vargas began the process to be a Habitat owner last May after the suggestion from her supervisor. The process involved a number of steps and requirements all geared toward ensuring the family gets the full benefit of home ownership and that it doesn’t become a financial burden. Prospective owners must meet certain financial requirements to ensure they can handle the no-interest mortgage.

On top of the 250 hours of “sweat equity” a future owner has to put into the effort, there are classes to attend that take the owner through all the aspects of home ownership, such as financial planning, contracts, taxes and what it’s like to deal with neighbors.

There also was the education Vargas said she got from being on a construction crew. In the required 250 hours, Vargas and her daughter, Lillian, worked on several Habitat homes, including the one that will soon be theirs. The other siblings didn’t work on the homes because they are underage. At the time Vargas and her daughter didn’t know they were working on their future home.

“The first day, we actually put up a wall,” she said. “I never thought I would get to do that. We hammered. We did some drywall. We shoveled dirt.”

Vargas said she now uses some of the skills she acquired on the construction crew to fix things around her current home, and she expects to be able to use some of that knowledge around the new one.

“In my rental, I fixed my sink. I learned how to change my air filters and other stuff around the house.” Vargas said.

Just days from moving into the new home, Vargas said there are still some family decisions to be made. With six people living in the home and four bedrooms, the math dictates someone isn’t getting their own bedroom.

“We’re debating that because my middle daughter (Vanessa), she’s a little messy,” Vargas said. “I told her if she keeps her room clean for a month, then she gets her own room. If not then she’s going to share. She’s working on it.”