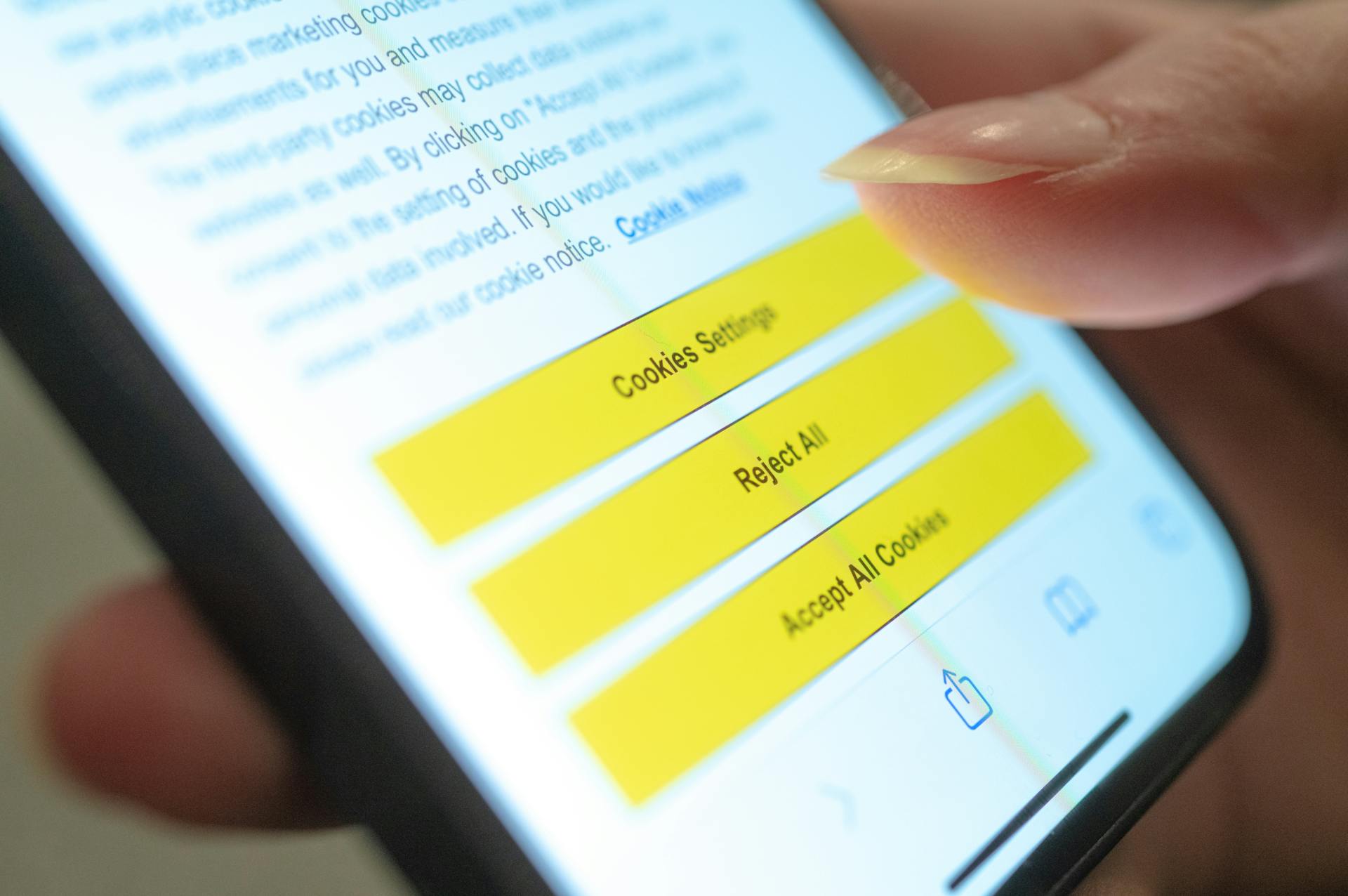

Cookie notifications become a ubiquitous aspect of online life. Mohssen Assanimoghaddam/picture alliance via Getty Images

Cookie notifications become a ubiquitous aspect of online life. Mohssen Assanimoghaddam/picture alliance via Getty Images

Website cookies are online surveillance tools, and the commercial and government entities that use them would prefer people not read those notifications too closely. People who do read the notifications carefully will find that they have the option to say no to some or all cookies.

The problem is, without careful attention those notifications become an annoyance and a subtle reminder that your online activity can be tracked.

As a researcher who studies online surveillance, I’ve found that failing to read the notifications thoroughly can lead to negative emotions and affect what people do online.

How cookies work

Browser cookies are not new. They were developed in 1994 by a Netscape programmer in order to optimize browsing experiences by exchanging users’ data with specific websites. These small text files allowed websites to remember your passwords for easier logins and keep items in your virtual shopping cart for later purchases.

But over the past three decades, cookies have evolved to track users across websites and devices. This is how items in your Amazon shopping cart on your phone can be used to tailor the ads you see on Hulu and Twitter on your laptop. One study found that 35 of 50 popular websites use website cookies illegally.

European regulations require websites to receive your permission before using cookies. You can avoid this type of third-party tracking with website cookies by carefully reading platforms’ privacy policies and opting out of cookies, but people generally aren’t doing that.

One study found that, on average, internet users spend just 13 seconds reading a website’s terms of service statements before they consent to cookies and other outrageous terms, such as, as the study included, exchanging their first-born child for service on the platform.

These terms-of-service provisions are cumbersome and intended to create friction.

Friction is a technique used to slow down internet users, either to maintain governmental control or reduce customer service loads. Autocratic governments that want to maintain control via state surveillance without jeopardizing their public legitimacy frequently use this technique. Friction involves building frustrating experiences into website and app design so that users who are trying to avoid monitoring or censorship become so inconvenienced that they ultimately give up.

Browser cookies explained.

How cookies affect you

My newest research sought to understand how website cookie notifications are used in the U.S. to create friction and influence user behavior.

To do this research, I looked to the concept of mindless compliance, an idea made infamous by Yale psychologist Stanley Milgram. Milgram’s experiments – now considered a radical breach of research ethics – asked participants to administer electric shocks to fellow study takers in order to test obedience to authority.

Milgram’s research demonstrated that people often consent to a request by authority without first deliberating on whether it’s the right thing to do. In a much more routine case, I suspected this is also what was happening with website cookies.

I conducted a large, nationally representative experiment that presented users with a boilerplate browser cookie pop-up message, similar to one you may have encountered on your way to read this article.

I evaluated whether the cookie message triggered an emotional response – either anger or fear, which are both expected responses to online friction. And then I assessed how these cookie notifications influenced internet users’ willingness to express themselves online.

Online expression is central to democratic life, and various types of internet monitoring are known to suppress it.

The results showed that cookie notifications triggered strong feelings of anger and fear, suggesting that website cookies are no longer perceived as the helpful online tool they were designed to be. Instead, they are a hindrance to accessing information and making informed choices about one’s privacy permissions.

And, as suspected, cookie notifications also reduced people’s stated desire to express opinions, search for information and go against the status quo.

Cookie solutions

Legislation regulating cookie notifications like the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation and California Consumer Privacy Act were designed with the public in mind. But notification of online tracking is creating an unintentional boomerang effect.

There are three design choices that could help. First, making consent to cookies more mindful, so people are more aware of which data will be collected and how it will be used. This will involve changing the default of website cookies from opt-out to opt-in so that people who want to use cookies to improve their experience can voluntarily do so.

Second, cookie permissions change regularly, and what data is being requested and how it will be used should be front and center.

And third, U.S. internet users should possess the right to be forgotten, or the right to remove online information about themselves that is harmful or not used for its original intent, including the data collected by tracking cookies. This is a provision granted in the General Data Protection Regulation but does not extend to U.S. internet users.

In the meantime, I recommend that people read the terms and conditions of cookie use and accept only what’s necessary.

___

Elizabeth Stoycheff has received funding from WhatsApp and Facebook for other endeavors, but that has no bearing on these research findings.

___

History of online security, from CAPTCHA to multifactor authentication

History of online security, from CAPTCHA to multifactor authentication

Updated

As more people have been moving their office work to remote computers, trying to hold secure meetings over technologies like Zoom from home or coffee shops is increasingly common. While some criminal activities like skimming your credit card at gas pumps may be falling out of fashion as fewer people commute every day, other activities, such as classic hacking, can thrive as long as people are using their computers to work remotely, opening new opportunities for hackers. In the past five years, there have been more than 2.76 million complaints to the FBI regarding various cybercrimes, including identity theft, extortion, and phishing, with losses exceeding $6.9 billion, according to 2021 data from the FBI.

With security top of mind, Beyond Identity collected information from think tanks, news reports, and industry professionals to understand landmark moments in internet security over the past 50 years. The internet began as a classified government program to connect different important military and government facilities. The first outside users were from universities, where very smart people have long been inventing new ways to poke holes in the internet as a form of preventive research.

From the first antivirus program in the 1970s to the zero-trust protocols of today, security has evolved over the years as developers strive to stay one step ahead of hackers.

1970s: Antivirus software

Updated

A computer virus is a piece of software the user typically downloads when they click on an infected email attachment or another file. The first virus was a 1970s program called Creeper, which was designed to crawl the early internet known as ARPANET, according to a report from Cyber Magazine. Like modern penetration testers, researchers wanted to see how they could hypothetically invade their own system. In response, email inventor Ray Tomlinson wrote a program he named Reaper, which chased and destroyed Creeper. That makes Reaper the first-ever antivirus program, creating a genre that endures today.

1970s: Encryption

Updated

Cryptography is the blanket term for the field of mathematics and security that involves setting codes and encoding information for safe transit. Encryption simply means applying a cryptographic algorithm to a piece of information. With computers, one of the first examples of network encryption came from IBM in the early 1970s. The first standard encryption algorithm, known as the data encryption standard, lasted for more than 20 years before computer calculations finally broke it. Today, researchers race to keep their mathematics ahead of those who are trying to use the same computing power to break the algorithms.

2000s: CAPTCHA

Updated

In the late 1990s, the internet was rapidly growing in popularity, with intrusive technology like cookies and viruses rapidly following. People realized they could use bots, or automated processes, to post spam comments on websites at a massive scale, for example.

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University invented CAPTCHA in 2000 as a way to combat those bots. Computer programs struggle with many tasks humans do almost without thinking, especially tasks that involve processing visual information. CAPTCHA is now considered deprecated in most usages, but it paved the way for other forms of security like the popular “Which of these pictures shows a motorcycle?” CAPTCHAs that are still used today.

2000s: Multifactor authentication

Updated

Multifactor (or two-factor) authentication is a form of login technology that asks users to offer a second, corroborative piece of information along with their simple username and password. This may come as a text message or through an app like Google Authenticator. While this technology dates back to the 1980s, it was first introduced to consumers in the 2000s when it rolled out to banks. The New York Times reported on the rise of two-factor authentication in 2004, a time when many Americans didn’t even have broadband internet yet.

2010s: Zero trust

Updated

If you’ve read this far, you may be starting to feel like no piece of data is ever safe. You’re not alone. Computer security is deeply complex and ever-changing because of the equal pace at which criminals and other bad actors are following new forms of intrusion. One of the latest paradigms is that of zero trust, a term that means doing away with previous ideas like “trusted devices.” This means always verifying security information on each device trying to access a network. Users would only be allowed access to data and information needed to complete a request.

This story originally appeared on Beyond Identity and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.