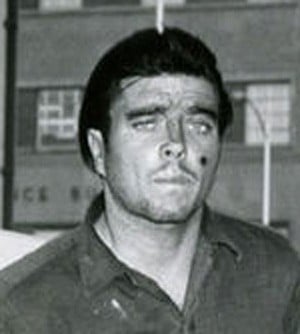

This uncredited photo shows Schmid as he usually appeared at his trial.

On Feb. 28, 1966, Charles Schmid Jr.'s mother testified as a defense witness for her son.

From the Arizona Daily Star, March 1, 1966:

Her Son By Choice

Mother Details Life Of Schmid

Who is Charles Schmid Jr.?

"He is my son by choice," Mrs. Katherine Schmid said yesterday. "He has lived at home since he was one day old."

Mrs. Schmid testified for two hours yesterday as a defense witness for her son who is charged with the murders of Gretchen and Wendy Fritz last Aug. 16.

"I did not like Gretchen because of the reputation she had," Mrs. Schmid said.

"Did you ever talk to your son about Gretchen?" Prosecutor William Schafer III asked.

"I did not."

"Did you ever talk to other kids at Charles' house about Gretchen and her reputation?"

"No. A Gloria Mees who worked at Hillcrest (a nursing home whcih Mrs. Schmid operated) told me of Gretchen."

"Was his relationship with Gretchen good?"

"The same as any other so-called romance."

"Did you ever see Gretchen at his house?"

"I did not."

"How many parties were held in your son's house in July and August of last year?"

"Four or five."

"Were you aware of the ages of the girls at the parties?"

"Some of them."

"Did you ever speak to Charles about this?"

"I did not."

"What were your son's duties at the nursing home?"

"He would do whatever I asked him."

"Did he have any regular duties?"

"No."

Mrs. Schmid said her son had been on an allowance since he was 16-years-old and that up until the time he was arrested last Nov. 10 she had paid all of his bills and had given him a $300 monthly allowance.

"Did Charles have anything in his boots?"

"He wore things in his boots to make him three inches taller."

"Did he ever practice walking with these things in his boots?

After a long pause, "Yes."

Mrs. Schmid said she went to her son's house, E. Adams St., which was next door to her home, two or three times a day and she cleaned it thoroughly once a week. She said she never saw anything that looked like a diary.

"Did you ever talk to your son about the disappearance of Gretchen and Wendy?"

"I asked him where they were and he said he didn't know."

"Did he ever say he knew anything about the disappearance of the girls?"

"He did not."

"How did you find out the girls were missing?"

"Mrs. Fritz called me. I told Charles later — thank goodness you were home last night."

The defense rested its case after Schmid's mother provided the alibi. She said Schmid came to her home on the evening of Aug. 16 and watched TV and ate pizza.

This conflicted with testimony by 17-year-old Edna Holder who had testified that Schmid and Paul Ginn left home early on that evening and didn't return until 1 a.m. the following morning.

Schmid's father recalled that she had called their son to ask him to turn down his music as his wife had said, but he didn't recall seeing Schmid later that evening on Aug. 16.

The case was expected to go to the jury sometime on March 1.

Meanwhile, an article in Life Magazine gave Schmid his "Pied Piper of Tucson" nickname and riled more than a few Tucsonans.

Here is the Star's take on the magazine article. From the Star, March 1, 1966:

Based On Schmid Case

City's 'Pied Piper' 'Outlined' By Life

Story Of Death, Gangs Described

Charles Schmid, now on trial for his life, is described in the March 4 edition of Life Magazine as a semi-ludicrous, sexy-eyed pied piper, who, stumbling along in his rag-stuffed boots, led Tucson teenagers in wild escapes from boredom.

As portrayed in the magazine, Schmid was not a freak hero to local youngsters, but "had for years functioned successfully as a member, even a leader, of the yeastiest startum (sic) of Tucson's teenage society."

One of the city's leading arteries, Speedway, is called a garish stretch of hamburger palaces and juke joints — and the favorite word of Smitty and his crowd.

Smitty's "crowd" had little to do but look each other over, the article continues. "Schools are beautiful but overcrowded; and at those with split sessions, the kids are on the lose (sic) from noon on, or from 6 p.m. until noon the next day."

Written by Don Moser, the Life story calls Tucson a city of glass and chrome and well-weathered stucco; "it is also gimcrack, ersatz and urban sprawl at its worst."

Following the disappearance of Alleen Rowe in May, 1964, her mother, Mrs. Norma Rowe, insisted that the police pick up Schmid. They did pick him up, the article reports but had no reason to hold him.

"The police, in fact, assumed that Alleen was just one more of Tucson's runaways," the magazine says, and claims that 50 runaways a month are reported to the Tucson Police Department.

Schmid, described by the magazine as wearing pancake makeup and a painted-on beauty mark, with dyed black hair and lips whitened, had a remarkable influence on high school girls.

One such girl, and one of the girls he is accused of killing, Gretchen Fritz, is described in the story as a "pretty, thin, nervous girl of 17 with a knack for trouble. A teacher described her as 'erratic and subversive.'"

Gretchen cut classes in school, the magazine article maintains. "She was suspected of stealing and when, in the summer before her senior year, she got into trouble with juvenile authorities for her role in an attempted theft at a liquor store, the headmaster suggested she not return and then recommended she get psychiatric treatment."

According to Richard Bruns, Schmid's friend who first told police that Schmid had murdered Gretchen and her sister, Wendy, 13, the relationship between Schmid and Gretchen was "an odd micture of hate and adoration."

At the time Schmid was dating Gretchen, Bruns was 18 years old, Life continues, "and Bruns had served two years in the reformatory at Ft. Grant. He had been in and out of trouble and never fit in anywhere."

Bruns, a major witness in the case against Schmid, decided to tell of Schmid's confession to the Fritz killings when he became obsessed with the notion that Kathy Morath, another Tucson teeager who had dated Schmid, "was the next victim on Smitty's list," the magazine says.

"At Bruns' frantic insistence, the police picked up Kathy Morath and put her in protective custody . . . They went into the desert and discovered the bodies precisely as Bruns had described them."

The arrest a week later of John Saunders and Mary French, with their testimony about the death of Alleen Rowe, resulted in the arrest of Charles Schmid for murder.

Life Magazine calls one disclosure of the trial "most disturbing."

One authoritative source, the article says, listened to the admissions of six high school students and said they unquestionably knew enough so that they should have gone to the police.

"There were indications that Smitty had boasted about the killings to his teenage followers long before authorities even began to suspect that murder might have been done."

"Nobody spoke up."

Life got at least one thing wrong. Schmid was arrested the same day the skeletons of the Fritz girls were found, not a week later or after Mary French and John Saunders were arrested.

Many Tucsonans felt the magazine got its portrayal of Tucson wrong as well. It was unflattering to say the least.

Next: The verdict.