It’s still dark outside when detectives Michael Buglewicz and Javier Chavarria pull into a mobile-home complex near Benson Highway.

The partners approach the front door of a home and direct another detective, Ryan Inglett, to the back. “He just came to the window,” Inglett reports.

The man inside, arrested in mid-December on charges of aggravated assault and criminal damage, was released from jail on the condition that he not return to the victim’s house. Today the three undercover detectives with the Pima County Sheriff’s Department’s domestic violence unit are on a “compliance check,” making sure the suspect is keeping that promise.

He’s not.

The detectives, dressed in plain clothes, don’t immediately show their badges. They look like regular guys with beards and baggy jeans. They’ve posed as plumbers a time or two, but most of the time they seem casual enough that unassuming offenders open the door to them.

That’s how it plays out this morning. Within 15 minutes, Buglewicz and Chavarria lead the man outside in handcuffs.

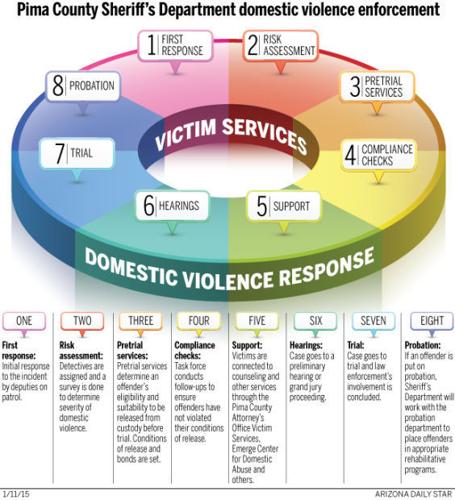

And so begins another shift on an innovative, multiagency domestic violence task force that aims to break the cycle of abuse.

“Just leave” is an unfair request

The task force, led by Sgt. Terry Parish, has one ultimate goal: “to disempower the offender.”

When Parish joined the unit in late 2013, he wondered why victims don’t just leave. He reached out to Emerge and other domestic violence groups to find the answer, and learned that many victims of domestic violence experience symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder or Stockholm syndrome, where victims held captive start to feel empathy toward their captors. They might have no money or job. Their abuser may have threatened to kill them if they try to leave, or to take away custody of their children.

Telling them to “just leave,” he learned, is “not a reasonable request.”

The system, as Parish found it, often re-victimizes victims. It was their responsibility to enforce the conditions of their abuser’s release. They’d see law enforcement officers only if they called 911.

The message they got was that they could not be helped. But the task force offers a different message: one of safety for victims and accountability for offenders.

Along with compliance checks, the Sheriff’s Department actively pursues fugitives and works with the court, prosecutors and support services to create a “family safety plan.” Those measures can prevent repeat offenses and even death.

The current enforcement model is supported largely by the U.S. Department of Justice Office on Violence Against Women’s STOP grants, which are awarded to help states strengthen their capacity to enforce and prosecute violence against women and provide better services for victims.

The Sheriff’s Department has been slowly changing the way domestic violence cases are handled as new approaches and resources became available. The compliance checks started last August — and already seem to be making a difference.

It’s too early to tell if conviction rates are up, but Pima County prosecutors say that, thanks to the task force’s intervention and ongoing involvement, abusers are abiding by court orders and showing up for their court dates more than they were before.

When suspects are caught violating a condition of release — which is a court order — they have little standing to fight in court.

After two domestic violence convictions, the next one automatically is a felony.

An invisible trap

It’s drizzly as detectives Buglewicz, Chavarria and Inglett drop off a suspect at the Pima County jail and head to the north side.

They’re after a man wanted in a domestic violence incident with his girlfriend. She had called for help when it happened, but by the time deputies arrived, he had fled.

Offenders like him often think they’re off the hook. In reality, they’re put on a “probable cause alert” that is shared with other law enforcement agencies.

Chavarria and Buglewicz first dropped by looking for the man the day before. They knocked on the door and searched the back to no avail. So they set an invisible trap, a way for them to tell if someone has entered or left the house.

Someone has.

As Buglewicz knocks on the front door, Chavarria goes around the backyard. He returns shortly after, shaking his head.

They’ve failed again, but they’re not about to give up. They’ll return and probably park outside, waiting until he comes out.

“Once you’re in scope, you will get caught,” Buglewicz says. “You’re in our world.”

Immediate help

The task force’s intensive, multilayered approach has made all the difference to a Tucson mother of two young children.

Last summer, an argument fueled by her husband’s drinking escalated into a shouting match that ended with him pulling out a gun and threatening to kill himself, and her.

One of their children watched in horror as he pointed the pistol at her head. To protect the children’s identities, the Star is not identifying her.

Once an energetic and positive woman, after that day she started to cry a lot and felt frustrated and afraid. She grew wary of her surroundings to the point of paranoia.

“It changed me at the core level,” she says.

Within days of the incident, she met with a detective who had her complete a risk assessment form and handed her a cellphone with the Emerge Center for Domestic Abuse at the other end of the line.

She and her children were immediately set up with counseling, monetary help and emotional support from the Southern Arizona Child Advocacy Center, Emerge and the victims’ services arm of the Pima County Attorney’s Office.

“When I need something, I call them,” she says. “It’s very calming, reassuring and in some ways, empowering.”

What’s kept her together, she says, is support from friends, family and continuing involvement from members of the domestic violence task force, whether it’s her assigned detective from the Sheriff’s Department, victims’ services or her case manager at Emerge.

Anna Harper-Guerrero, vice president for organizational development at Emerge, says she has not seen a collaboration like this in her 18 years of work with domestic abuse.

The center, which provides shelter, counseling, job training and other services to victims, is in constant communication with the Sheriff’s Department, she says. The two agencies share the risk assessment forms and jointly determine the best course of services, one victim at at time.

The Tucson mom is a living testament to the power of that cooperation. Without the support, she says, “there’s a good chance one or more of us could be dead.”

A lot of chasing

On their third run of the day, just past 8:30 a.m., the detectives visit an east-side business.

A man in his 20s who works there had reportedly gotten violent with his mother and destroyed some of her belongings in anger, but by the time deputies responded, he had disappeared. That put his name on the probable cause list.

Under the STOP grant, the task force has 21 days to catch a suspect who has fled a scene. After that, the case is forwarded to the Pima County Attorney’s Office and on to warrants detectives in the domestic violence unit.

The warrants guys do a lot of running and chasing, Chavarria says. He knows. He used to be one.

This morning, with some time to reconsider, the man’s mother has asked for the aggravated assault charges against her son to be dropped. That happens a lot, but it doesn’t let suspects off the hook. Detectives are still pursuing him for criminal damage.

The detectives work with his boss to get him into a back room where they can talk with him quietly, rather than chase him down in a scene that could turn violent.

Chavarria extends his hand. His badge is showing. He explains to the man that they’re going to take him to the Sheriff’s Department for questioning.

The man complies at first, shaking detectives’ hands and nodding. But he becomes increasingly agitated as it becomes clear that he’s getting arrested.

He begins cursing. A few expletives later, at the first sign of physical resistance, the detectives grab and handcuff him, then escort him out of the building.

Emotions run high

The Pima County Sheriff’s Department alone gets 4,000 domestic violence calls a year.

And virtually every one of them is inherently dangerous to victims and officers alike.

By the time a victim calls 911, someone is terrified, injured or worse. Emotions and tensions are sky-high.

The threat of more violence is always there.

Just two weeks ago, a 24-year-old Flagstaff police officer was gunned down while responding to a domestic violence call.

Dealing with domestic violence every day, members of the task force get pretty good at reading people, Buglewicz says. The plain-clothes attire helps, too. Uniformed officers are far easier to target.

But the task force members believe that what they’re doing can stop a cycle of violence that can lead to generations of despair.

“We can change the model of how we handle domestic violence,” Parish says.

More satisfying

When Buglewicz, Chavarria and Inglett try to take a few minutes to sit and discuss their jobs, Chavarria’s cellphone almost immediately starts buzzing.

“They’re waiting for us,” he says. An interrogation is about to begin.

On his way down the hall, Buglewicz mentions that he used to be a traffic officer. He felt good about getting drunk drivers off the roads and making them a little safer. It was his way of contributing to the world.

The risk level of what he does now may be higher, but “I’m more passionate about this.”