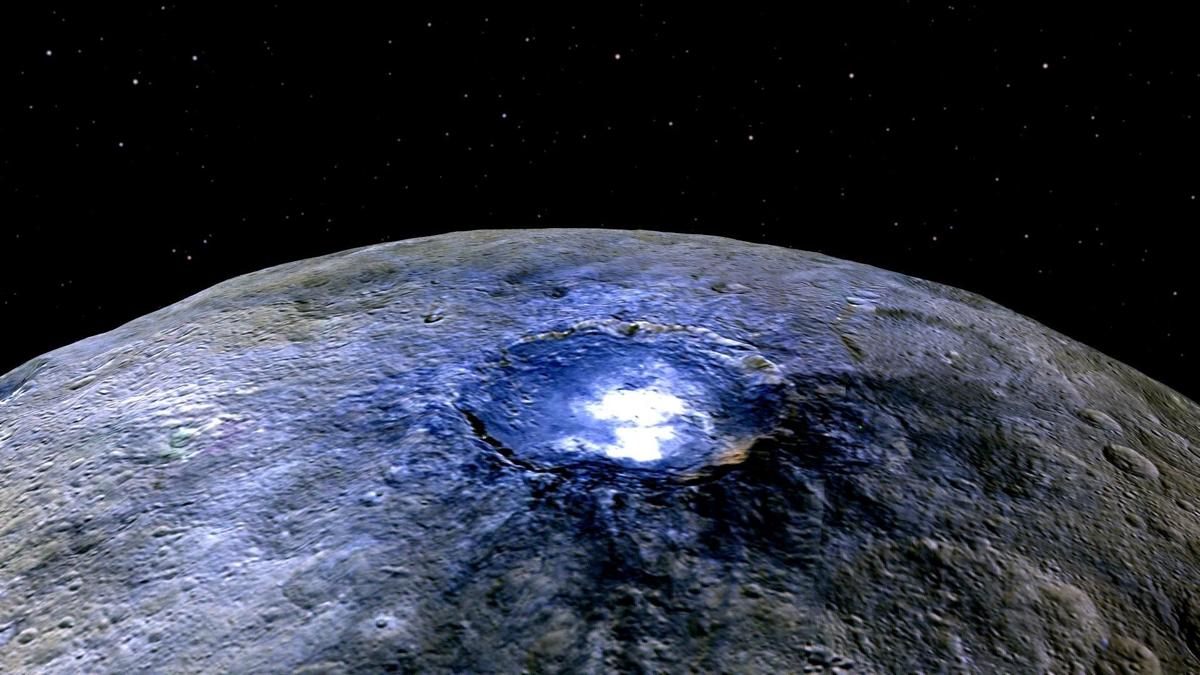

Scientists may have resolved the riddle of those mysterious bright spots on the dwarf planet Ceres, which is still being orbited by NASA’s Dawn spacecraft.

A team of researchers, including five from Tucson-based Planetary Science Institute (PSI), propose in a paper published in the journal Nature this week that the bright material, found mostly within craters on Ceres’ otherwise dark surface, is composed of salts left from brine whose water has sublimated.

The bright spots first appeared a year ago in photos sent to Earth by Dawn’s framing camera as it approached the planet. Salts and ice were the early guesses by scientists.

Some commenters on the Dawn Mission website suggested the bright spots were beacons of an alien civilization.

The paper in Nature, whose lead author is Andreas Nathues of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany, proposes a more mundane explanation.

Dawn launched in September 2007 for its long, slow haul to the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, where it first orbited Vesta before heading to Ceres, the queen of the asteroid belt, containing 25 percent of its overall mass.

Arriving at a salt explanation was a “process of elimination,” said PSI research scientist Lucille Le Corre.

Using images taken through seven color filters on Dawn’s camera, the team compared the spectral signature of the ice to those of the possible candidates.

“We compared with water ice, and clays initially. Salt was the best match for the brightness and the shape of this color spectrum,” Le Corre said.

Vishnu Reddy, another PSI research scientist on the team, said the spectral identification, suggests a type of magnesium sulfate, akin to Epsom salts.

That’s not a definitive result, Reddy said. Determining a unique signal for salts is difficult.

“It’s really hard to do from orbit and you need a sample, basically.”

Scientists are now seeking explanations for how the brine was exposed. Meteoritic impacts are suspected in some recent craters.

At the biggest bright spot, in a 60-mile-diameter feature named Occator Crater, scientists have also seen a haze that may be water still sublimating from the crater.

That suggests some activity is exposing subsurface water, said Reddy and Dawn images show what looks to be a network or cracks in the crater.

“Something is causing it to periodically be active,” he said.

Scientists hope to learn more from the next mapping run. Dawn has just reached its lowest orbit, 240 miles above the surface of the planet, and will begin taking and transmitting higher-resolution photos and other scientific data later this month.

“We will definitely get a better idea of what is causing these cracks, more information about the source or cause of it,” Reddy said.

Le Corre said she expects the team’s findings to be bolstered by a closer look, but she is open to surprises.

“We will maybe get a confirmation of what we found or we might find something else.”