The mirror blank for the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope has been moved a few feet at a time over the past seven years by its creators at the University of Arizona’s Richard Caris Mirror Lab.

It is now being boxed for a much bigger journey.

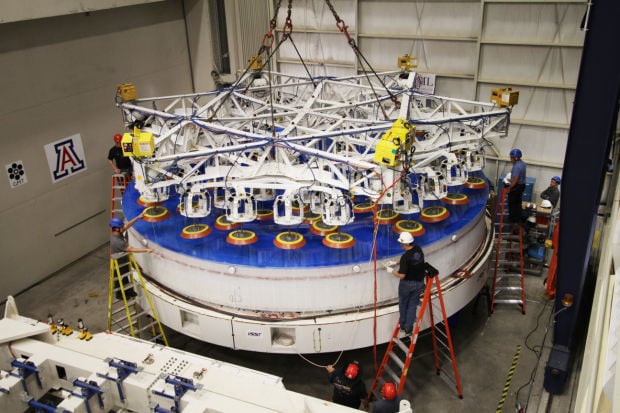

On Wednesday, it was lifted from its testing cell and lowered onto the bottom of a 36-ton metal crate. It will eventually be shipped, by truck and boat, to a mountaintop in Chile.

Together with its glass mirror blank and cell, the load will weigh 50 tons, said Bill Gressler, who handles logistics for the telescope and site.

From its perch in the Andean foothills, LSST will make the deepest, widest, fastest movie ever made — a movie of the entire sky visible from Cerro Pachon that will help astrophysicists uncover the secrets of dark matter and energy and the history of the universe.

It will also reveal, on a nightly basis, 1 million transient events or “things that go bump in the night,” as Steward Observatory astronomer Philip Pinto puts it — exploding stars, moving asteroids, possibly planets in our own solar system beyond Pluto.

It will undoubtedly uncover things astronomers have never seen before.

Pinto said the LSST is a shift in thinking for the current generation of giant telescopes. Its 8.4-meter (27.6 feet) mirror was designed to deliver a wide field of view — 49 times the area of the moon as seen from Earth — as opposed to the much narrower view afforded by telescopes with similar-sized mirrors that concentrate on pinpoint resolution.

“The idea is to look at all of the sky as often as possible, about every three days,” said Pinto.

“The other radical new way of thinking is you do one very carefully done set of observations, then everyone uses it to do science, sort of like the human genome projects.”

The massive flow of data — 20 to 30 terabytes per night — will require the services of one of the largest supercomputers in the world and a computer sorting system, yet to be devised.

First, though, it required a mirror, unique in the world, to create that wide field of view on a giant telescope that must pivot and point quickly and accurately.

“There has never been a telescope that moves around the sky this quickly,” said Gressler, project manager for telescope and site with the LSST Project Team.

Including two mirror surfaces on the one giant slab made it possible to devise a compact telescope with a wide field of view, he said.

One of Gressler’s logistical tasks is to deliver the mirror and its cell to the end of a winding mountain road in the foothills of the Chilean Andes. The last 25 miles is not paved and has grades of up to 16 percent.

Among the restrictions along the way is a tunnel at Puclaro Dam, which is 11 meters wide (36 feet). The box containing the LSST mirror is 30 feet square. It was made by Tucson’s CAID Industries, which has made the steel shipping containers for all of the UA’s mirrors.

Gressler has an immediate logistical challenge. He has to move the mirror from the UA’s Mirror Lab, where four giant mirrors are in various stages of completion and space is at a premium.

He has found space in a hangar at Million Air Tucson, a concierge service for private jets at Tucson International Airport.

That will require a slow nighttime drive on a flatbed truck from UA Stadium and permission from the Federal Aviation Administration to widen a gate.

The mirror will come back for final testing in about two years before starting its longer journey by truck, probably to the port of Houston, where it will be loaded onto a ship for its voyage to La Serena, Chile.

Making unique mirrors is basically the job description at the mirror lab which, under direction of founder Roger Angel, set out to make the largest single mirror surfaces in the world.

Its borosilicate mirrors, cast in a spinning furnace beneath the bleachers of Arizona Stadium, are honeycombed with air pockets to produce mirrors that are both rigid and lightweight.

The technical teams at Steward have perfected the process over the years, but that doesn’t make it easy.

“It’s a unique mirror. There has never been another one like it,” said Buddy Martin, who headed the effort of grinding and polishing the mirror to exacting tolerances.

The LSST is two mirrors in one. The primary mirror, which collects the light from the night sky, is on the outer edge. It reflects light to a secondary mirror being made elsewhere, which, in turn, reflects that light to the interior edge of the mirror. From there it is directed to the instrument that records it — a giant 3,200-megapixel camera, the largest ever made, sitting right above the hollow center of the LSST mirror.

When he began the task, Martin thought it would take the usual two years, but soon realized that he was polishing two mirrors with “additional complexity because the shapes had to be coordinated in a way we’ve never done before.”

Testing also became more complex, he said. The outer mirror had to be tested 20 meters above the surface and the inner mirror at 8 meters. That meant reconfiguration of the testing tower.

Completion and testing of the mirror was cause for celebration in January for the corporation formed to build it, the Tucson-based LSST Corporation.

It put together a variety of philanthropic and institutional sources to get the project started, with the expectation that it would become part of a federally-funded telescope project.

Research Corporation for Science Advancement provided seed money, along with early involvement by the University of Arizona and the University of Washington.

Richard Caris, for whom the mirror lab is now named, made a $2.3 million contribution in 2005 to start casting the mirror.

In 2008, LSST received $20 million from the Charles Simonyi Fund for Arts and Sciences and $10 million from a charity headed by Bill Gates.

Now that the National Science Foundation has approved construction, LSST Corporation is turning over the mirror to a newly created AURA center, operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy.

LSST Corporation will now concentrate on developing the science tasks for the telescope and will continue to raise money for costs not covered by the NSF or the Department of Energy, which is funding the camera.

Institutions across the country are participating in the LSST. The University of Arizona, one of the founding partners along with Tucson-based National Optical Astronomy Observatory, would like to continue to play a pivotal role, said Dennis Zaritsky, deputy director of Steward Observatory.

It has plans to robotocize telescopes on Kitt Peak, Mount Bigelow and Mount Graham to respond “quickly and intelligently” to unusual objects found each night by the big survey telescope, said Zaritsky.

It also aspires to be a “science center” for LSST. That role has not yet been defined, but there is already interest and involvement by a variety of UA departments, from computer science to physics to astronomy. “We hope to be a hub,” he said.

It’s been a long time coming. Planning for the telescope, led by Angel and former Steward Director Peter Strittmatter, began long before the mirror was cast in 2008, said Zaritsky.

The observatory is now in construction phase. In August, the National Science Foundation authorized $27.5 million in the current fiscal year and approved an overall construction budget of $473 million.

Plans for fabrication of its $165 million camera by SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory were approved by the U.S. Department of Energy in January.

Construction is expected to be complete by 2019 and the plan is to begin the ten-year survey of the night sky by 2022.