PHOENIX — After 10 years, 30 nominees and decades of discovery, the first National Native American Hall of Fame will induct 12 honorees in October.

Arizona’s Lori Piestewa, the first Native American woman to die in combat as a member of U.S. military, is among those who will be celebrated.

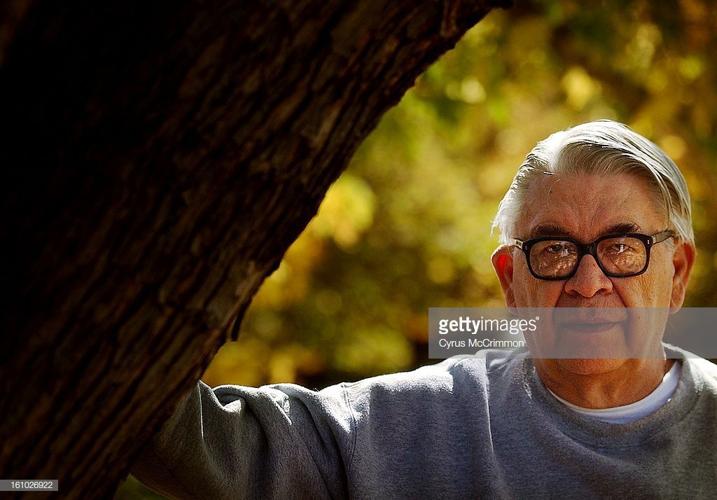

So is the late scholar Vine Deloria Jr., author of “Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto”, who was a professor of political science at the University of Arizona from 1978 to 1990. At the UA, he was instrumental in establishing the first master’s degree program in American Indian Studies in the United States.

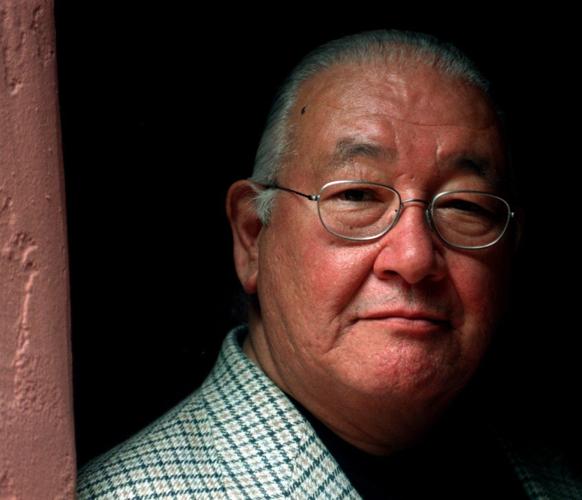

Another former professor at the UA, Pulitzer Prize-winning author N. Scott Momaday, will also be honored. Momaday, who wrote “House Made of Dawn,” lived in Tucson for a number of years.

Many of the inductees, such as Olympic star Jim Thorpe, astronaut John Herrington and Maria Tallchief, the first Native American to be a prima ballerina, are well known and have been lauded with awards and honors.

But something was still missing, said James Parker Shield, a member of the Chippewa Tribe and chief executive of the Native American Hall of Fame, who dreamed of the hall for a decade.

There’s a National Women’s Hall of Fame and others honoring various groups, he said.

“But there’s no hall of fame for Native Americans, and I think that there should be,” Shield said.

Harvard professor Phil Deloria, the first tenured Harvard professor of Native American history and the son of inductee Deloria, said Shield’s work is valuable.

“Like all halls of fame, it calls attention to certain kinds of extraordinary people who provide role models and opportunities to think about the world in which those folks lived and acted,” he said. “It starts conversations, it establishes aspiration.”

Shield said he pushed to make the hall as inclusive as possible. That started with a voting process in May encouraging Native Americans to weigh in on who, among 30 people nominated by the hall’s board, should make the finals.

“We didn’t want an over-representation of any one particular tribe,” said Shield, who wanted to avoid a “popularity contest.”

He and board members chose the inaugural group based on leadership, legacy, mentorship and sacrifice. The honorees represent 10 tribes in eight categories, such as science, athletics and advocacy. Six are women.

Piestewa will be the only hall of famer recognized for her military service. The 23-year-old Army soldier fought in the Iraq War and was captured in the early days of the conflict. Piestewa was gravely injured and died in a hospital before she could be rescued.

Piestewa Peak and the Piestewa Freeway in Phoenix were renamed in her honor. Shield said family members from Tuba City, Piestewa’s hometown, are expected to attend the Oct. 13 ceremony at Steele Indian School Park in Phoenix.

Ryneldi Becenti, who was born and raised in Fort Defiance, Arizona, as the first Native American woman to play in the WNBA, was in the inaugural class of nominee, but not chosen as an inductee. She played for the Phoenix Mercury from 1997-98.

Becenti, who said humility is a characteristic of the Native American people, said her mentors and teammates deserve credit. The award, she said, brings honor to inductees’ tribal nations.