Authorities are struggling to deal with pollution that streamed from two old mines into Patagonia-area canyons during recent storms in the form of orange sludge and reddish-brown liquids with a milky coating.

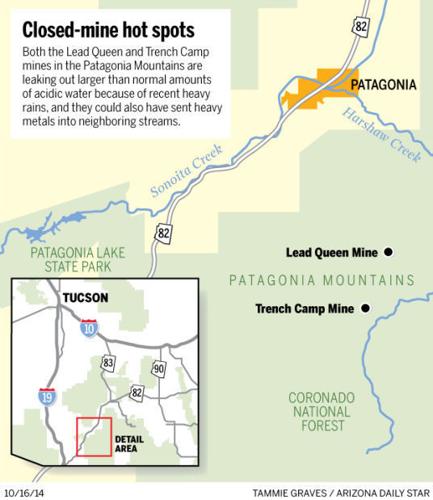

The heavy rains of mid-September washed out acids, minerals and possibly heavy metals into two canyons, both of which eventually drain into Harshaw Creek, said Floyd Gray, a U.S. Geological Survey official in Tucson who went to both sites and collected samples of the contamination.

Harshaw Creek, whose watershed supplies part of Patagonia’s town water supply, is a tributary to Sonoita Creek, a stream that’s long been beloved by bird-watchers and other naturalists.

The private owner of one mine site has been cited for numerous violations of state rules because of discharges containing acids and other contaminants into a neighboring creek. The other mine, on Forest Service land, received no citations but faces a potentially difficult task in obtaining federal money for a cleanup. For the moment, nothing is in place to stabilize the mine sites although the runoff has dropped off considerably since the rains stopped.

The rains caused a breach of tailings piles at the old Trench Camp Mine, which until a few years ago was owned by Asarco. It leached out potential toxins from underground tunnels there, as well as at the old Lead Queen Mine, on Forest Service land. The mines lie about 12 and six miles almost due south of Patagonia, respectively. The Lead Queen Mine closed in the 1940s and the Trench Mine closed in the 1970s or early 1980s, although both mines date back much earlier.

The acidic water leaving the mines was nothing new because acids from these and other mines have been washing into those streams for years, Gray said. What caught people’s attention this time was the orange sludge and reddish-brown stream water, which was caused by minerals such as iron and manganese. While those substances aren’t dangerous, they are indicators that toxic heavy metals could be in the water, said Gray. The white coating was likely toxic aluminum, he said. Results of tests for the metals are due in a few weeks.

“This happens every year but not the way it happened in September,” Gray said. “We’ve got a dynamic problem, in that these things are engineered up to a point, but these rains have exceeded that capacity.”

“These were fast-occurring storms in which the monsoon didn’t taper off in September like it usually does,” Gray said. “Things got backed up (at the mine sites) because the area wasn’t draining fast enough.”

The water leaking out of Lead Queen and Trench Camp had pH levels of 2 and 3 respectively. At Alum Gulch, the canyon leading from Trench, the pH level was 4.7. A pH of 7 is considered neutral; the lower the number, the more acidic the water.

The contamination was first spotted in late September by Gooch Goodwin, a Patagonia resident and environmental activist who had gone hiking into the unnamed canyon that drains from the Lead Queen Mine.

Walking upstream about 1.5 miles below the mine site, “I could see red sediment in the canyon, and the further up I went, the deeper the red got,” Goodwin recalled this week. “By the time I got within a half-mile of the mine site, the water was running blood red. It had a weird odor to it, almost like a petroleum odor.”

While house-sitting near the Trench Mine, he decided to check out that site and saw red water crossing the road, said Goodwin, who is with the Patagonia Area Resource Alliance.

Last week, the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality issued a violation notice to a private environmental trust that now owns the Trench Mine. Six significant violations of state rules were alleged, including unauthorized discharges of the reddish-brown liquids, failure to document conditions at the site and violating state water quality standards.

The Asarco Multi-State Trust now has to figure out how to stabilize the tailings so they won’t wash out again. Andrew Steinberg, the trust’s vice president of operations, would not comment on the notice, saying he has to first discuss the matter with ADEQ. The trust is a for-profit organization formed to manage and reclaim the mine property after inheriting it after the Asarco bankruptcy during the 2000s.

The violations carry no designated fines, and state officials will take into account how the trust responds to the violation notice in determining whether it will be fined, ADEQ Director Henry Darwin said.

In 2009, the trust was established to clean up this, two other contaminated Arizona mine sites and numerous other Asarco-owned sites across the country as a result of a legal settlement of the Asarco bankruptcy. Asarco paid $23 million to clean up the three Arizona sites, with $2.3 million of that set aside for work at Trench and the Salero Mine site north of Patagonia.

“The Trench tailings impoundment never broke before,” said Gray, who described the impoundment as an earthen dam near where the tailings come out at the head of Alum Gulch, a creek. “The earthen dam always worked before, but the water this time was so high that it breached and broke it and came across with the red stuff.”

A set of artificial wetlands, built to hold back water flows coming from an artificial mine shaft, also was overtopped and broke, Gray said.

At the Lead Queen Mine, Forest Service officials are trying to figure out how to contain the polluted runoff for the short term. They were originally thinking about putting bales of straw into the creek as a way to filter out minerals and some of the thicker metals, acting as a “choke point” so they didn’t continue downstream, said Mark Ruggiero, the service’s Sierra Vista District ranger.

That idea has now been largely scrapped because officials concluded that the straw bales could hold up sediment in the creek and cause erosion, said Coronado National Forest Supervisor Jim Upchurch.

For a longer-term cleanup and stabilization of the area, the Coronado will have to obtain money from the national or regional Forest Service offices, Upchurch said. Or, the service could obtain money from the federal Superfund toxic waste cleanup program.

Both Upchurch and ADEQ director Darwin said they don’t yet know exactly what caused the polluted runoff to leave the canyon. “You don’t know if it’s fractures in the rock, adits (horizontal mine shafts), tunnels — it could be a combination of that. I don’t know if we’ll ever find out what’s happening,” Upchurch said.

Similarly, Darwin said he doesn’t know how long it will take to fix up the Trench site so it won’t send more polluted runoff toward Harshaw Creek. “It boils down to what’s causing it,” he said.