Jacquelyn Hinek said her chance at a traditional college experience imploded eight months after she arrived on the University of Arizona campus.

On April 19, 2013, Hinek — a freshman — went to a party attended by multiple UA football players, some of whom she knew from her job as a student equipment manager for the team.

Hinek later told police that she had a few drinks while talking to a friend. Eventually, she saw some people she knew go into one of the apartment’s bedrooms and followed them.

Hinek sat down on the bed and, she said, everything went dark. She later told police she must have passed out. She woke up sometime later, unable to move her body.

Hinek said she slipped in and out of consciousness over the next several hours as she was sexually assaulted and beaten by five men associated with the football program — one of whom was Hinek’s supervisor. She said at least three other men watched the attack. Someone recorded the incident on a cell phone, later sharing the video with other students.

Ultimately, three of the men involved in her assault were disciplined by the school.

While the experience itself was horrific, Hinek said it got worse once she decided to report the incident to police and the UA. She said the lack of services available on campus left her isolated and pushed her to the brink.

In the years following her assault, Hinek has learned that what happened to her is more common than she realized at the time: 23% of undergraduate women experience sexual assault on college campuses, according to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network.

The Star reported on Hinek’s assault in January, along with six other incidents involving football players accused of sexual assault, harassment or domestic violence. Some of the incidents took place while Hinek still was a student. She told the Star that her experience would have been different had she known there were other victims on campus.

“I really didn’t know. I feel like there must have been such a community of us without even knowing it,” Hinek told the Star in March, speaking publicly about her assault for the first time. “If I had known someone else, that would have changed a lot for me, because I wouldn’t have felt so alone and I would have had other people to lean on instead of myself.”

Hinek graduated from the UA and channeled her experience into a career. She now runs a Southern California emergency shelter for victims of sexual assault and intimate partner abuse, and also heads up a countywide emergency hotline to connect victims with services.

She acknowledges that had she not been assaulted, she may not be working in her field now.

“It feels really sad, but my college experience ended in April 2013,” Hinek said. “From then until two years later, it was just an absolute nightmare. I lost so much, but a big piece of it was losing my ability to just be a college student. I didn’t sign up for that. (The UA) owed me more than that.”

• • •

Hinek wasn’t interested in a career in sports when she took the scholarship position with the football team.

“It was really just a job that seemed probably cooler than working at the cafeteria,” she said. “It sounded interesting and I thought I can make money and do something that’s a little more fun.”

She continued working with the football program for about six months after her assault, but she said pervasive sexual harassment eventually led her to quit.

In talking about her assault, Hinek says that she can break the aftermath into two distinct parts: before she reported, and after she reported.

“In the direct aftermath … I was really just trying to kind of keep going,” she said.

She was also confused about what had happened to her, saying she didn’t know a lot about sexual assault and people that she talked to for the most part told her the experience didn’t amount to rape.

“Me now, knowing as much as I do and being older and wiser, I’m like, ‘Hell no, that was so messed up. That was sexual assault,’” she said. “At the time, I was getting a lot of input from other people that caused me to question what happened to me, so I kind of just said, ‘This happened, and I’m going to move on.’”

Hinek initially decided to move on without reporting, which she said was hard. She was having nightmares, and she said players and other students were telling her to keep quiet about the incident.

Then she took an internship with the UA group Students Promoting Empowerment and Consent (SPEAC) and ended up working at Campus Health’s Oasis Sexual Assault and Trauma Services. While there, she connected with a woman who became her support system. Hinek decided to report.

Hinek told officers that she wanted to be able to one day tell her kids she did the right thing.

She first reported the assault to campus police, even though it had happened at an apartment off campus. She called her encounter with the University of Arizona Police Department terrible, saying that the officer who took her report told her she was the type of person he told his daughter not to become. She ended up filing a complaint with the school about him.

Her experience with the Tucson Police Department was completely different.

“I mean, it was hard. No matter how great they are, it’s a difficult experience, but the detectives I worked with were supportive and caring,” she said.

TPD’s investigation lasted for several months, but none of the men involved in the assault were charged with a crime. Prosecutors said they couldn’t prove that the sex wasn’t consensual.

Hinek still wasn’t sure if she wanted to alert school officials. Then Susan Wilson in the UA’s Title IX office reached out to Hinek to interview her regarding the sexual assault of a student Hinek knew. That student’s situation also involved members of the football team.

“I just felt like, ‘this is meant to be.’ I’d been considering it, and for her to reach out, it kind of felt like a bridge and a connection,” Hinek said. “I also thought this happening to someone else in the athletic department was ridiculous. It’s easier when you think it doesn’t affect anyone else. I could live with that. But when I was realizing that it was happening to other people, I just felt sick about that and I felt like the school needed to know.”

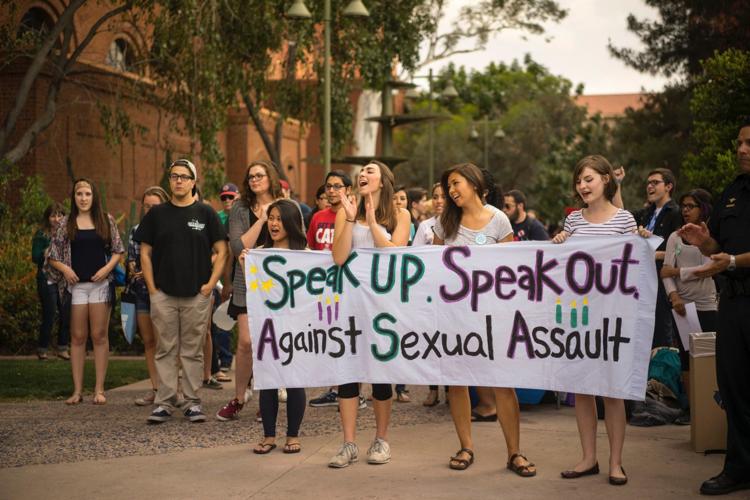

Jacquelyn Hinek, center, claps her hands during a Take Back the Night rally at the UA. Hinek interned with the group Students Promoting Empowerment and Consent, and eventually pursued a career working with survivors of domestic and sexual violence.

• • •

Hinek calls the subsequent Title IX investigation, which took roughly six months, the worst experience of her life.

“I think about it a lot and I regret that I didn’t fight harder. I’ll always look back and wonder, could I have done more?” she said. “But I’m proud of myself, because while I kind of lost that fight a bit, I was up against (the UA). It was just me, by myself, completely alone against them.”

Hinek said she didn’t think the investigation would be as lengthy or arduous as it turned out to be.

“I think for a while I really believed in them and felt like (the investigation) may be going somewhere,” Hinek said. “They were asking questions and wanted to know about my experience, but when I look at the results, it’s just this realization that they never intended to help me.”

By the time the UA closed its investigation in April 2015, two of the men who were ultimately disciplined had already left school. Student equipment manager Dale Stewlow, who was Hinek’s supervisor when she worked for the team, had taken a job at the University of Nevada prior to the school issuing its one-year suspension for sexual misconduct. Clive Georges, a wide receiver who appeared on the UA’s 2012 and 2013 rosters, transferred to North Dakota in January 2015, four months before he was expelled from the UA for his role in the assault.

UA officials told Hinek they had scheduled interviews between Tucson police, and that players would meet detectives on campus to help facilitate them. She learned differently when she read the Star’s story. Tucson police reports say that when they arrived on campus, school officials told them that on the advice of university attorneys, they would only tell the suspects and witnesses that the police wanted to talk to them. It would be up to the individuals to decide if they wanted to participate in the investigation.

“When I read that, it didn’t surprise me at all,” Hinek said. “I understand that when they have police coming on site, they might have a lawyer for those students … but if I’m a student as well, don’t they have to kind of ride that line in between?”

After Hinek reported the situation to the UA in October, she was told that because it was football season, the school would have to wait for a break to interview the players. On her end, though, Hinek felt like the investigation consumed her life.

“They would tell me to come in and I was there. Granted, I was motivated to do it because I wanted this process, but it was such a big part of my life,” she said. “Responding to emails and going to meetings and preparing for things. Making sure that I provided everything that they wanted.”

At one point, Hinek said she was told that she needed to be more considerate of the players and what they were going through during the process. When Hinek would confront the school about the length of the investigation, she said she was given excuses about the players’ schedules.

“I just thought, ‘this isn’t the way it’s supposed to be,’ but I was not empowered at all. I think back and I realize I was a teen-ager dealing with this on my own, and they have unlimited resources and so much knowledge and know-how,” she said. “The fact that they would let me do that on my own is astounding. That they didn’t say, ‘Hey, this is a really complicated process for a lot of people. Are you needing us to provide you with someone to consult with?’”

Hinek said she asked the school to connect her with a counselor or financial support to pay for one. She said her requests were denied.

The Star reached out to the UA last week for a response to some of Hinek’s statements. A university spokesman said: “The University, out of respect for the survivor’s account and understanding that this event occurred six years ago, will not challenge the survivor’s remembrance.”

• • •

In the past year, the UA launched its Survivor Advocacy program and made numerous changes to its Title IX office.

In November, the school hired former South Tucson judge Ron Wilson as its Title IX director, and in January changed his title to president for equity and inclusion and Title IX director.

Wilson has rewritten the school’s Title IX policy and is awaiting approval of the draft. He’s also hired Thea Cola, formerly from the Women and Gender Resource Center, to create curriculum surrounding consent and Title IX for students and faculty. The school also recently launched a Consortium on Gender-Based Violence, which is working with the Title IX office to create a curriculum around bystander intervention, toxic masculinity, sexual assault awareness and prevention and mental health.

The Survivor Advocacy program, launched in August, includes two full-time sexual assault advocates. The program’s website directs students to campus resources, including counseling, psychological and legal services, and also has links to outside agencies that can provide help.

Meetings with advocates are confidential and don’t lock a student into filing a formal complaint or initiating an investigation. Advocates help students understand their rights and options and can provide emotional support, safety planning, help with academic and housing accommodations, mental health support, assistance navigating the Title IX, UA appeal process and filing a police report.

Advocates can also help students obtain an order of protection and connect them with an outside agency that will send someone to accompany them to court, should a criminal case progress to that level.

Brenda Anderson Wadley, one of the program’s two full-time survivor advocates, said she has connected with hundreds of students since the program’s launch.

Wadley says the first few weeks of classes and final exams are the busiest times of each semester. She refers to those stress-filled times as “the red zone.” College students nationwide tend to seek more services during those times, Wadley said.

There are also more social activities happening during those times, which can lead to an increase in sexual assault.

Wadley said the program made contact with 170 students during the fall semester. This semester, advocates have already contacted more than 100 students.

Things were especially busy in January, when UA President Robert C. Robbins sent out a campus-wide email about the program and other available services. Contact from students also increased during Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s contentious confirmation hearings, Wadley said.

Services for students don’t end after initial contact with a survivor advocate, Wadley said. Many students continuously visit, and some students have been seeking support since the beginning of the year. Most students are seeking mental health and academic accommodations. Some professors are supportive, Wadley said; she meets with the ones who initially aren’t.

Wadley said she lets students guide the advocacy process, telling her and her colleague what they need.

“A lot of time when violence happens, folks’ agency is taken away,” Wadley said. “My whole job is focused on how am I giving this student their agency back? How am I supporting the student and centering their needs and wants?”

Wadley said that while she’s excited to work with Wilson in the Title IX office, there needs to be a culture shift on campus. She’d like to see athletics, Greek life and the law school involved, instead of the handful of specialty programs that have currently taken up the cause.

It “has to be a university-wide thing,” she said.

Wadley said she’s seen some students who have come to the program for help teach other students how to become their own advocates. She thinks the university is doing a good job and has taken significant steps, but there’s still more work to be done.

• • •

By the time the school issued its decision in April 2015, Hinek had taken her finals early and gone home for the summer. She graduated that December, a semester early, but said the ongoing investigation left her feeling like she had to be available at a moment’s notice and prevented her from traveling during spring break or studying abroad.

While she was interning with SPEAC, Hinek saw a presentation by a Southern Arizona Center Against Sexual Assault advocate and realized that’s what she wanted to do with her life.

Prior to graduation, Hinek began working full-time at the SACASA, which while challenging at first, helped her to give back and helped other people with experiences similar to her own.

“My experience with the assault and aftermath has really inspired me to help other people,” Hinek said. “For me, I didn’t even know what my options were, so a big driving force for me is that I don’t care if someone chooses to do nothing, as long as they know that they can do something. As long as they know what their options are, whatever they decide is fine with me.”

She says that when she talks to other survivors, she provides education on healthy relationships and consent, but lets each person define his or her experience.

While the work is empowering and makes her feel good, she also feels melancholy at times, knowing the potential path survivors are headed down when they decide to go forward.

April 19 marked the six-year anniversary of Hinek’s assault, and she says time has helped her heal.

“What I would want to go back and tell myself is that what happened to me is not OK and, ‘Trust yourself,’” Hinek said. When she decided to report, “it just became so obvious that no matter what they’re trying to make me feel, that was rape. I knew that I had to do something about it, and somewhat naively I thought that would be the right thing to do and I would make an impact and change.”

Hinek said that she constantly asks herself if she would report her assault to the UA again, if given the choice to do so. She says that she’s grateful for the career and relationships she’s made, so it’s difficult to say she wishes she hadn’t reported because she doesn’t know where she’d be if she hadn’t.

“I’m glad that I reported it, but I regret that the following years were what they were,” she said.

The decision to go public is not one she took lightly. But silence and anonymity for the past six years has done nothing but protect the men who assaulted her, she said.

“I think there’s been this unspoken contract where they just bet I wouldn’t say anything to anyone and what they did to me was so horrifying that I’d be too embarrassed to tell and just keep it secret for the rest of my life,” Hinek said. “I’m proud of myself and what I went through and I have no regrets. I have nothing to hide and there’s nothing that I won’t stand behind.”

By putting a name to her story, Hinek hopes to legitimize her assault in the eyes of people who may think that her anonymity lessened what happened to her and to help other survivors struggling to cope with their own experiences.

Hinek’s one regret is that her lack of resources and inability to hire an attorney perhaps allowed the school to fall short in its duty to her, to provide support and a timely investigative process.

“I was just up against a lot more than I ever thought I was up against,” she said. “I thought I was up against the men who raped me. I didn’t know I was up against them and the University of Arizona.”