I’m a treasure hunter. Not keen on contemporary collectibles, I’ve long surrounded myself with unique items, those with history.

Occasionally , an object reveals far more than what initially caught my fancy.

In 1991, while living in Mesa, I discovered “Wild Bill’s Emporium” in the nearby former mining town of Globe. Housed in a once grand yet now decrepit building, it was dimly lit and chock full of thousands of objects.

Scattered, not displayed. Not a single price tag.

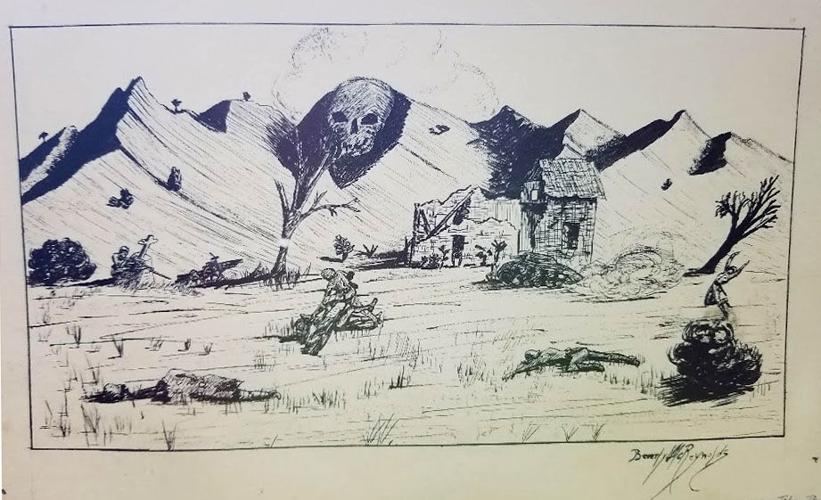

Among treasures culled from chaos was an 8-by-6-inch line drawing on aged , yellowed paper. Presiding over a charred landscape of carnage, the skull-faced mountain took my breath away. In swift, deliberate strokes, it depicted soldiers in the act of killing or dying. Some already dead. This product of an imagination left little to imagine.

The drawing was signed and dated and had clearly been executed by a talented hand. I had to have it. I think I paid a dollar for it, perhaps $3. To me, it was priceless.

Upon acquiring it, something new piqued my interest. Barely visible were thumbtack holes in each corner. Far more subtle than the arresting content, they proved equally evocative. They were proof that someone had valued the piece, wanted to look at it. And that it had been taken down. That the drawing even still existed meant whoever “was done with it” did not wish it destroyed.

Living with it

I had the artwork professionally framed and displayed it in my home for many years. It was the centerpiece of our “Black & White” wall. Over time, I made several assumptions: that the artist had lived what they depicted, that they struggled with trauma. I wondered if, given limited therapeutic interventions at the time, they’d succumbed to suicide.

At some point, I brought it to my workplace, where I teach psychology and oversee a counseling program. I thought it would be a good fit for classroom discussions on art therapy and of interest to student veterans with whom I work. It has proven to be both.

But I began to question keeping it, thinking something so deeply personal should be returned to the artist or their kin. And I hoped to be granted permission to keep a copy.

In 2017, after 26 years of stewardship, my quest to return it began.

Seeking Beverly, finding Bill

The date and place on the drawing were readily discernible. The signature, not so much. The last name was clearly McReynolds, and I thought the first name Beverly. But I assumed that was a woman’s name, and was confident women were not in combat the year it was made. So I looked for Benny and Bennet and Benjamin McReynolds. And I came up blank. Time and time again.

Eventually, I sought the help of my friend Mary, who in short order, found record of a Beverly L. McReynolds, Staff Sgt., 301 Coast Artillery — World War II. He died in 1950 at age 31. She also discovered that he had a son, Bill McReynolds, who lives in Tucson.

Finding Bill, learning about Beverly

In December 2017, I mailed a carefully worded letter to Bill McReynolds explaining who I was, my reason for reaching out, a description of the drawing and my contact information. In the event that he was not “the” Bill I sought, or, if he was, did not wish to see the drawing, I did not include an image of it.

As it turned out, Bill was Beverly’s son, and he did want to see the drawing.

In his first reply, Bill McReynolds sent a sample of his father’s earlier works, drawings done before the war. He hoped they’d help me discern if what I had was of his father’s hand. And they did confirm such. And so I sent him a photo of the drawing.

And thus began a years-long, continuing correspondence.

In his next reply, Bill McReynolds generously stated that he wanted me to keep the drawing to continue educating and supporting others. And he sent additional photographs of his father: as a young man; a formal Army portrait; relaxing with comrades on a hillside; in his casket.

Bill does not remember his father. He was very young when his parents divorced, shortly after his dad returned from overseas. He was just 5 years old when his father died.

Bill McReynolds told me all he knew of his father’s service, acknowledging that details were few.

Beverly L. McReynolds joined the Army pre-war, in 1939. He came home on leave in 1944 when Bill was born and was discharged in 1945.

He’d spent time in Panama. Given the number of troops needed to guard the canal and build infrastructure, it is probable he was likewise engaged.

He fought during the battle of Manila in the Philippines and may have been involved in other aspects of the liberation.

He was in combat in New Guinea at some point during that campaign.

On an unknown date, McReynolds was injured in combat, and fellow soldiers dragged him through the jungle to safety. Given that Bill has letters dated 1942 referencing hospitalization for his father’s spinal issues, it is probable his father sustained injury while in New Guinea.

Between 1945 and his death in 1950, McReynolds lived with or near his mother. She saw firsthand his daily struggles and campaigned to understand and reverse a significant drop in his government-issued disability benefits.

In a draft letter to the VA written shortly after her son’s death, she wrote: “He went into the army a perfectly normal, healthy boy, he returned with a painful back injury and so very nervous. He was married to a lovely girl and had a fine baby boy born after he left this country for his second foreign service.”

She then described how the combination of his nervous condition, physical and emotional pain and worry about finances made McReynolds so difficult to live with that his wife divorced him. The dissolution of his family exacerbated his emotional struggles and his physical condition worsened.

Despite corrective post-war surgery, McReynolds was left in chronic pain with partial paralysis that inhibited his ability to draw or paint. Given descriptions from his mother and grandmother, Bill McReynolds suspects his father suffered from PTSD.

The late McReynolds remarried, and under the Rehabilitation Act he entered art school to become a commercial artist. Despite multiple absences due to recurring pain, he did complete the course of study.

During a phone call with his mother on May 10th, 1950, McReynolds told her he’d not been sleeping. No matter what position he tried, he told his mom, his lower body would twitch and jerk. McReynolds said Anacin and aspirin did “positively no good”.

According to a brief story in the local newspaper on May 13, 1950, McReynolds had taken several sleeping pills, cut an artery in his right arm, then shot himself through the heart with a .45 caliber revolver. Thus, his death was ruled a suicide. As Bill McReynolds has said, “It’s clear he was serious in his effort to end his life.”

Back to the drawing

McReynolds dated his drawing May 8, 1943, Talara, Peru.

Talara is a port city. In 1942, U.S. forces began building barracks and other structures there so it could operate as an air base and refueling station for the Pacific fleet. The island was not the site of active combat.

So, what about the drawing? Why then, there? My best guess is that Beverly McReynolds drew the memory of his recently acquired combat injury while temporarily safe in a no combat zone. He may even be the soldier depicted getting shot in the back.

We will never know.

Meeting Bill

In May of 2023, after 29 years away, I traveled to Arizona for my niece’s graduation from ASU.

There was no way I could be so (relatively) close to Bill without trying to meet him. Bill was delighted at the prospect and thankfully my husband Jeff was totally on board.

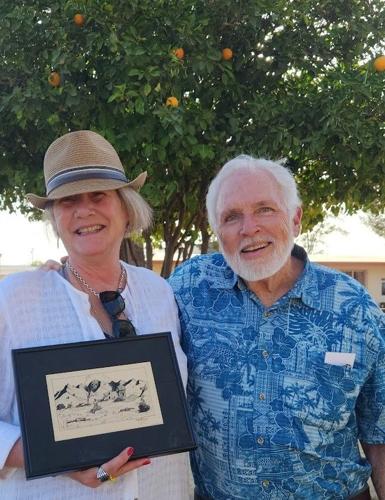

Nancy Adams and Bill McReynolds pose with a drawing McReynolds' father, Beverly McReynolds, made when he was stationed overseas during World War II.

We rented a car, drove to Tucson. And when I first saw Bill sitting in our pre-arranged meeting place, I nearly fainted. I’d studied his father’s visage for years and the resemblance was uncanny. Here was Beverly McReynolds’ son, the same movie star good looks untouched by time. And we shared a deep, heartfelt hug. He misty-eyed. Me full on crying. And together we three drove to South Lawn cemetery where Beverly McReynolds rests beside his beloved mother. We paid our respects.

Bill got to see and hold the drawing made so long ago by his father. The little piece of art whose power transcends time.

Legacy

Like countless others, Bill is the child of a casualty of war and knows firsthand that “damages inflicted on the military person often carry down to family members and even future generations”. As he grew up, no one spoke much of Beverly McReynolds, which Bill feels is due to the nature of his death and his mother having remarried.

Though he did not know his father, Bill believes the event of his death impacted his own life and life decisions.

Clearly, in the decades between McReynolds’ wartime experiences, subsequent suicide and the present, there has been much research into, and increased awareness of, the impact of trauma, dynamics of suicide, and need for ongoing support as service personnel transition to civilian life. Equally true, there is much more the collective ought, and can do, to serve those who have served.

Staff Sgt. Beverly Lionel McReynolds, 301st Coast Artillery, WWII, was born on Oct. 4, 1918, in Beattie, Kansas. He died on May 13, 1950, at his mother’s home in Tucson. He was 31 years old.

Veterans Day honors men and women who have served in the US armed forces.