On Sept. 24, 2023, a space mission led by the University of Arizona is expected to return to Earth with samples from the asteroid Bennu.

Exactly 159 years after that, Bennu might just show up to reclaim what was stolen from it.

Newly refined orbital projections based on data collected by the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft give a 1 in 2,700 chance that the asteroid will impact Earth on Sept. 24, 2182. (That’s a Tuesday, if you’re trying to plan your week.)

NASA video explains how and when the asteroid Bennu might impact the Earth, though the chances at very slim.

A devastating collision is also possible — though even more unlikely — in 2187, 2192, 2193 and 2194.

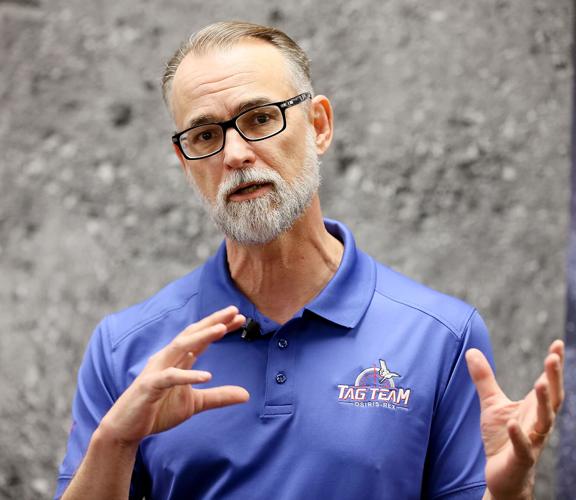

“Nobody should be losing sleep over a potential Bennu impact. It’s a long way into the future, and it’s a relatively small likelihood,” said Dante Lauretta, OSIRIS-REx principal investigator and a professor in the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona. “The odds of that impact occurring are about point-zero-five percent.”

Lauretta is one of 18 authors of a new scientific paper, published Tuesday in the journal Icarus, that provides the most detailed look yet at what is known about Bennu’s orbit around the sun and the danger it poses to Earth.

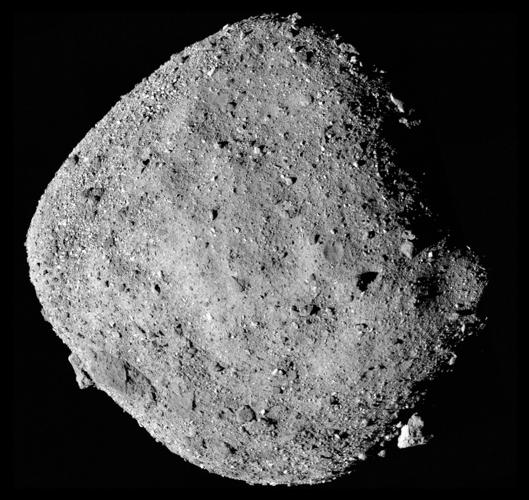

Space mountain

The asteroid is roughly the size of Pusch Ridge in the Catalina Mountains, “so you can imagine if that was flying at you from outer space that, you know, you’d be a little bit worried about it,” Lauretta said.

Whether Bennu ultimately hits Earth late in the 22nd century will be decided by an earlier encounter in 2135, when the asteroid will sweep past the planet at roughly half the distance to the moon.

Davide Farnocchia is a scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California and the lead author of the new orbital analysis.

He said there is “no possibility whatsoever of a collision” in 2135, but that near miss could alter Bennu’s orbit just enough to set it on a collision course decades later.

Still, he said, there is a 99.94% chance that the asteroid won’t hit Earth at all — at least not for the next 300 years or so.

“We shouldn’t be worried about it too much. The impact probability is small,” Farnocchia said.

Bennu was first discovered in 1999. Scientists have known for more than a decade that it could pose a threat to Earth some day.

According to NASA estimates, such an impact would equal about 1,400 megatons of TNT or 93,000 times the explosive energy of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima — a huge calamity, though not enough to wipe out life on Earth.

“Bennu is a potentially hazardous asteroid,” Lauretta said. “In fact, it ranks at the top of the list NASA keeps of potentially hazardous asteroids. But it’s still a very small probability.”

S for security

OSIRIS-REx was launched in 2016 to study the spinning top of rocky debris in hopes of learning about the formation of the solar system and the origins of life. The unmanned probe arrived at Bennu in December 2018 and scooped up some pebbles and dust from the asteroid’s surface on Oct. 20, 2020.

Though entering orbit around Bennu and collecting a sample was the primary mission, charting the future course of a potentially deadly asteroid was also a key objective. After all, the second S in OSIRIS-REx does stand for security.

Lauretta said the spacecraft was on what NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office refers to as a “transponder mission,” using its own proximity to Bennu to collect data about the asteroid’s position and movement with unparalleled accuracy.

Lindley Johnson, planetary defense officer for NASA, described the resulting measurements as “exquisitely precise” to a level never captured before for an asteroid.

Farnocchia said what scientists already knew about Bennu’s orbit from 10 years of observation from Earth has been “improved by a factor of 20” by the OSIRIS-REx mission.

And researchers expect to be able to refine their understanding even more once the spacecraft returns with its precious cargo.

In addition to gravity, Bennu is propelled by forces created as the asteroid’s surface heats and cools, something called the Yarkovsky effect. By directly analyzing some of the material the asteroid is made out of, scientists should be able to accurately estimate how much of a push Bennu gets from the effect.

“It’s a very dark asteroid. So think of a parking lot in Tucson in July … the same thing is happening with the asteroid’s surface,” Lauretta said. “We really want to understand the physics of that process: How does it absorb that sunlight, how does it reemit that energy back into space, and most importantly, is that going to change?”

Playing defense

What scientists learn about Bennu should improve their ability to predict the orbits of other asteroids, including those that may pose a threat to Earth.

NASA is also testing ways to nudge asteroids off course before they strike our planet. Later this year, the space agency plans to launch a spacecraft and crash it into a moonlet of the asteroid Didymos in 2022 in hopes of altering the smaller space rock’s orbit.

But a big part of protecting the planet is discovering dangers in time to do something about them. As Johnson the planetary defense officer put it: “We now know a lot about Bennu, but what else is out there?”

By some estimates, only about one-third of all potentially damaging near-Earth objects have been identified, leaving some 15,000 large asteroids and comets still to be discovered.

To that end, NASA has approved another UA-led space mission to find, track and characterize as many threats as possible in our celestial neighborhood. The Near-Earth Object Surveyor is an infrared space telescope that will serve as both a scientific instrument and a dedicated first line of defense.

The mission, led by UA professor Amy Mainzer, is now in the preliminary design phase, with launch anticipated in 2026.

By then, researchers at the UA and around the world hope to be hard at work on the first batch of Bennu samples set to be released for study.

OSIRIS-REx left the asteroid and headed for home on May 10. So far, everything is going according to plan.

“The mission is in great shape right now,” Lauretta said on Wednesday. “The spacecraft is basically on cruise control.”