He was a history teacher for more than three decades, teaching on military bases all over Germany, packing up a camper and his family for extended summer vacations, hitting all the great historical spots across Europe.

So it’s not a surprise that when Michael Gary Allen hops on a bicycle, he’s prone to lose himself in thought.

But these are a lot of miles. And a lot of thought. After all, Allen is a former U.S. Olympian and a former ultra-ultra marathoner who once ran almost 500 miles in six days.

Even at 88 years old, he still pushes himself, which is why Allen will ride in El Tour de Tucson on Saturday, and why he expects to ride the next three years.

This is not a rational man we’re talking about.

Michael Gary Allen

“My dad will say there are two kind of ultra-runners in their approach to escape from the pain of their body,” said his son, Mont, a history professor at Southern Illinois University. “Some focus very closely on the surroundings — the minutiae, the buildings, the ground. They’ll study everything. My dad, he completely ignores the outside world and just lives in a fantasy world while he’s out there. He does it by escaping into historical fantasy.

“He just imagines what it would be like to talk to Julius Caesar in Ancient Rome or to Genggus Khan on the Mongolian Steppe or Jesus Christ.”

So even though he’s on a bike by alone, he’s not exactly by himself.

In the sixth grade in 1947, Allen says, his nickname at school was “Fatty.” He was a chubby, poor student with chronic asthma.

In the seventh grade, he picked up a newspaper route for the Los Angeles Examiner, and, later, the Los Angeles Times. He lost some weight, switched schools to a larger public school and by the time he was in high school, he went out for and made the Cross County team.

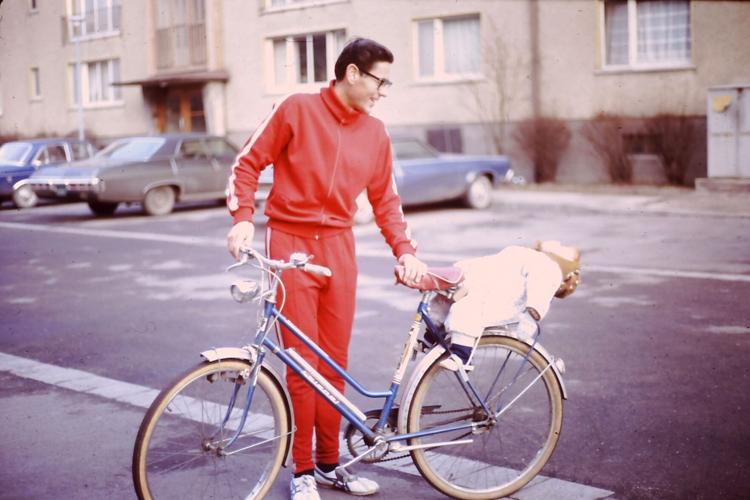

An avid bicyclist for decades, Mike Allen is pictured in 1972 with his infant son, Mont Allen, passed out asleep on the back of bike.

He was on the “B” team, but, still, he made it. The next year, he was last place on the B team for a school that wasn’t noted for its athletics.

He aspired to letter, and he resolved to train every day, and he joined the football team as a center, the fulcrum point of a single-wing offense.

By the end of his senior year, he had the school record for the mile.

Roughly 10 years after he started to focus on fitness, he was the third-ranked marathon runner in the country. But his body was breaking down, leg injuries in his mid-to-late 20s starting to take over.

He’d joined the army after a semester at Santa Monica Junior College, and almost immediately decided to try out marathoning. In 1954 he took part in the Western Hemisphere Marathon in Culver City, then the third-oldest marathon in the country behind Boston (1897) and Yonkers (N.Y., 1907), and finished third. He took leave in 1955 to head to the Berkeley Marathon and bested eight other runners to win the race, which was held in the rain. With 1956 an Olympic year, he was placed on the Armed Forces Olympic training team at the age of 20 and sent to Fort Devens, Mass. to train for the Boston Marathon. After being shipped out overseas, he returned in 1958 and won the Western Hemisphere Marathon in 90 degree heat — “Wearing low cut canvas top tennis shoes and wool socks!” he said — but that was just about the peak of his running career.

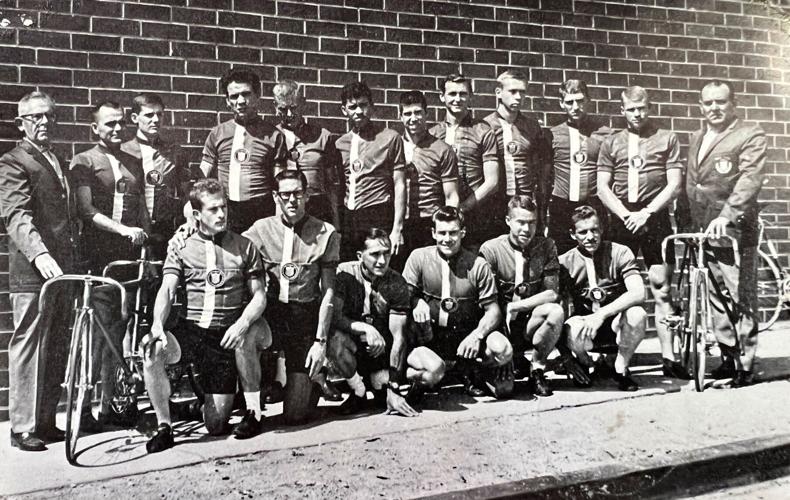

Mike Allen wins a regional Olympic trial at Lake Mathews in Southern California in the mid-1960s.

He was ranked 3rd in the country — “Not by time, but just because of who I beat” — but a series of leg injuries kept him out in 1959 and 1960.

His Olympic dreams derailed, he began matriculating at Cal Poly Pomona when he returned to his family home one day, “and in the middle of the living room was a red Ideor Asso bicycle.”

“My mother spent $135 and she had to borrow $100 from Uncle Bob,” he said. “I’m choking up here. Can you imagine you’re a mother going to a brother and borrowing $100 in those days? I walk in and my mom says to me, ‘Quit feeling sorry for yourself. Just make the Olympics on the bicycle.”

She told him a story about his father, who had died in 1947.

In 1908, Allen’s father had tried out and failed in the Olympic cycling time trial.

Now Allen had a new goal. Father in his father’s bicycle tracks, but get over the hill.

Speaking of over the hill, Michael Gary Allen may be a couple years shy of his 10th decade, but he remembers the 1964 Tokyo Olympics like it was yesterday.

“It was like being a child at Disneyland 24/7,” he said. “I’ve got chills all up and down my spine right at this second. Once you make an Olympic team, everything becomes quasi-real. You live in a surreal world.”

His journey to Tokyo began in earnest in the beginning of 1963. He began training in the orange groves of Orange County and in nearby San Bernardino. There wasn’t much by way of official distance bicycle training regimens, so he created his own, based on his own marathon training. He eventually started riding from Fontana to Big Bear Lake.

He shocked the competition by winning the 1963 California State Road Cycling Championship (southern section) and his friend and training partner, two-time Olympian Skip Cutting, told Allen about a 100-kilometer road race and time trial in New York City.

“As soon as I saw they would have a time trial event, I thought I’d make the team,” he said.

He did. He won the trials. He was officially a 1964 Team USA Olympian.

“I ran into a bar to call my mother. But I had no change,” he said. “So I called her collect, and she picked up the phone, and all I said was, Hi, mom, I won.’ We both started crying. After 3 minutes, the operator comes on, ‘Sorry I’m going to have to cut you off now.’ She thought someone had died. There I am in a bar, in my shorts, and everyone in the bar wants to buy me a drink.”

He’d only really been on the bike for a few years, and here he was, headed to Tokyo.

It just so happened that the cycling time trials were on the first day of competition, “which meant I didn’t have to train! Just, eat, sleep and watch the Olympics. You’d wake up in the morning, ‘What am I going to do all day and all evening?’”

He had a chance to explore the city, less than two decades removed from World War II.

“Growing up in school, you’re in class, and there were three pictures on the wall — one of Hitler, one of (Hideki) Tojo and one of Mussolini,” he said. “And if the teacher said Hitler, ‘We went, boooo.’ If she said Tojo, we hissed. If the teacher said Mussolini, we said hee-haw, hee-haw. You remember that at the age of 10, and then in the span of 20 years, politically and economically, it was like how could the world change so much?”

But it was over as quickly as it had started.

“When you get on the bus after the Olympics, you talk about a bummer. You could hear a pin drop,” he said. “It’s all over. For a number of athletes, they’re already thinking four years ahead. But I was 29 and it was all over for me.”

Allen cycled for another two years, got married, moved to Germany and taught.

But that would not be the end of his athletic career. Far from it.

Mike Allen (29 years old at the time; front row, second from left) poses with the rest of the 1964 Olympic road cycling team. The team competed in the 100-kilometer road race in Tokyo in 1964.

His cycling days over for the most part, Allen got back to running. And running. And running.

By the mid-1970s, he was considered top 10 nationally in race-walking (50km) and by the end of the decade, he was going much further.

In 1979, he participated in the New York City Invitational 100-Mile Run, and by the mid-80s, he was competing in — and winning — ultra marathons. At the age of 51, he set the U.S. Open Track record by going 473.25 miles at the Weston Six Day Run. For his age group, the record stood for more than a quarter-century.

As late as 65 years old, he set what is believed to be a world record for his age group at the Grapevine, Texas, Ultracentric 48-hour run, going 158 miles, 1,447 yards.

What could possibly motivate someone to push their body in that way?

“Psychologically, I’m still the fat kid who needs to stay thin,” he said.

Somehow, he has not transferred that onto his son.

“How do you live up to an Olympic athlete?” Mint said. “Bless his soul, he never prompted me to exercise or put expectations on me. All he emphasized was learning. He got his bachelors in social science, his masters in history, and he made a decision to either stay with his dissertation and get his PhD to become a professor or take up a teaching job and marry my mom. He did that. So if you ask my dad, ‘Did you ever hope your son becomes an athlete,’ he’d say, ‘No, a thinking human being. Maybe a professor.’ So, if you ask him, in a weird way he’s living vicariously through me.”

Father and son, they share a tremendous passion for teaching and for history.

“Normally your dad’s a teacher, and it’s the worst. It’s the opposite with me,” Mont said. “My dad was the most popular guy on campus. He would transport kids with his stories.”

Every year, Mont makes a post on the school Facebook page about his dad, and comments come pouring in.

So what keeps him ticking? Why does he climb aboard that bike, every single day?

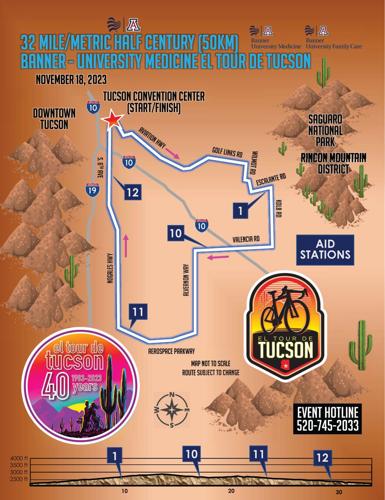

“Cycling gives me a goal,” Allen said. “When I wake up in the morning, I never have to suck my thumb and think what am I going to do today? Well, I’m going to ride my bike for 10 to 30 miles. I’m thinking past El Tour this year. My goal is to do the 50k until I’m 91.”

His son wonders what life will be like for his father after that. He’s worried about inertia setting in.

“It’s not just about having the wind in his face,” Mont said. “He needs to have an event he’s aiming for. That doesn’t mean he has to beat other people. He’s out there to beat himself, or his previous records, or just to do something novel.”

There will be a time when that is not possible. Mont fears that.

“He does nothing but work out and spend time at home,” Mont said. “He’s an introvert but a gifted faker. Being around other people exhausts him but he knows now to turn on the charm. Teaching is all theatre and he’s amazing like that. But he doesn’t really talk to anyone but me and my mom.”

Oh yes, he does.

Just get him on a bike.

Then he’ll have a great talk with Caesar and Genhgis Khan.

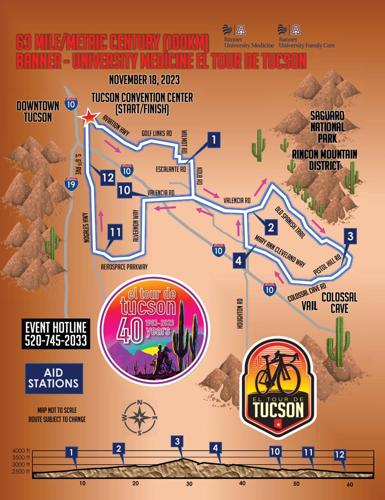

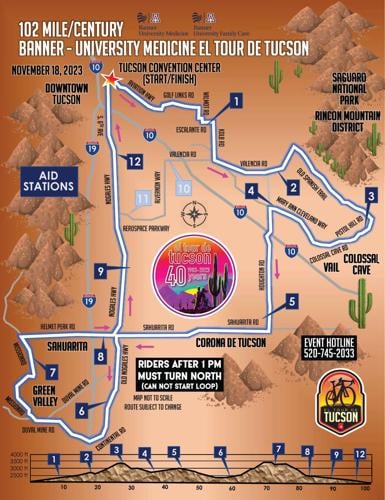

Watch: El Tour de Tucson's inaugural race was held in 1983 and over the past 40 years, the event has provided pro riders and novices alike the chance to take to the streets.

The 40th annual El Tour de Tucson will be held Nov. 18, 2023.