The silver mines of the Cerro Colorado Mining district in Santa Cruz County have attracted the attention of miners who worked the narrow quartz veins in sedimentary volcanic rocks for several hundred years.

Located 55 miles southwest of Tucson among the rolling grasslands along Arivaca Road between Amado and Arivaca, the Cerro Colorado Mine is classified as one of the earliest mining operations after the Gadsden Purchase of 1854.

Known for its high-grade surface silver it was worked by Charles D. Poston and Herman Ehrenberg from San Francisco, the former acquired $100,000 in cash to invest in 80 mining claims near the old Tumacacori Mission and the Santa Rita Mountains to the east.

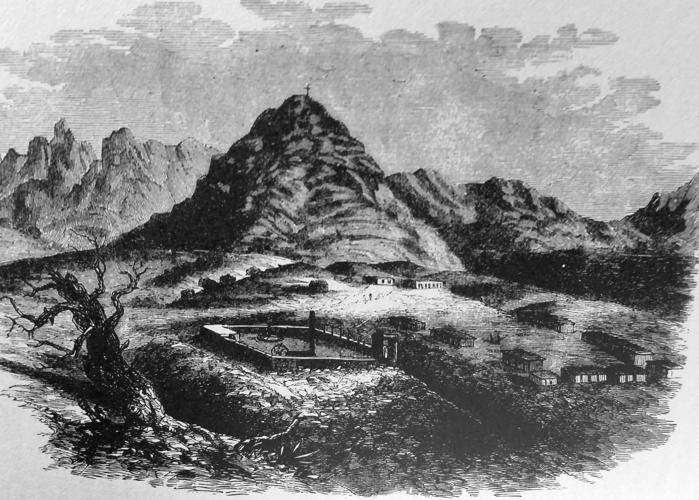

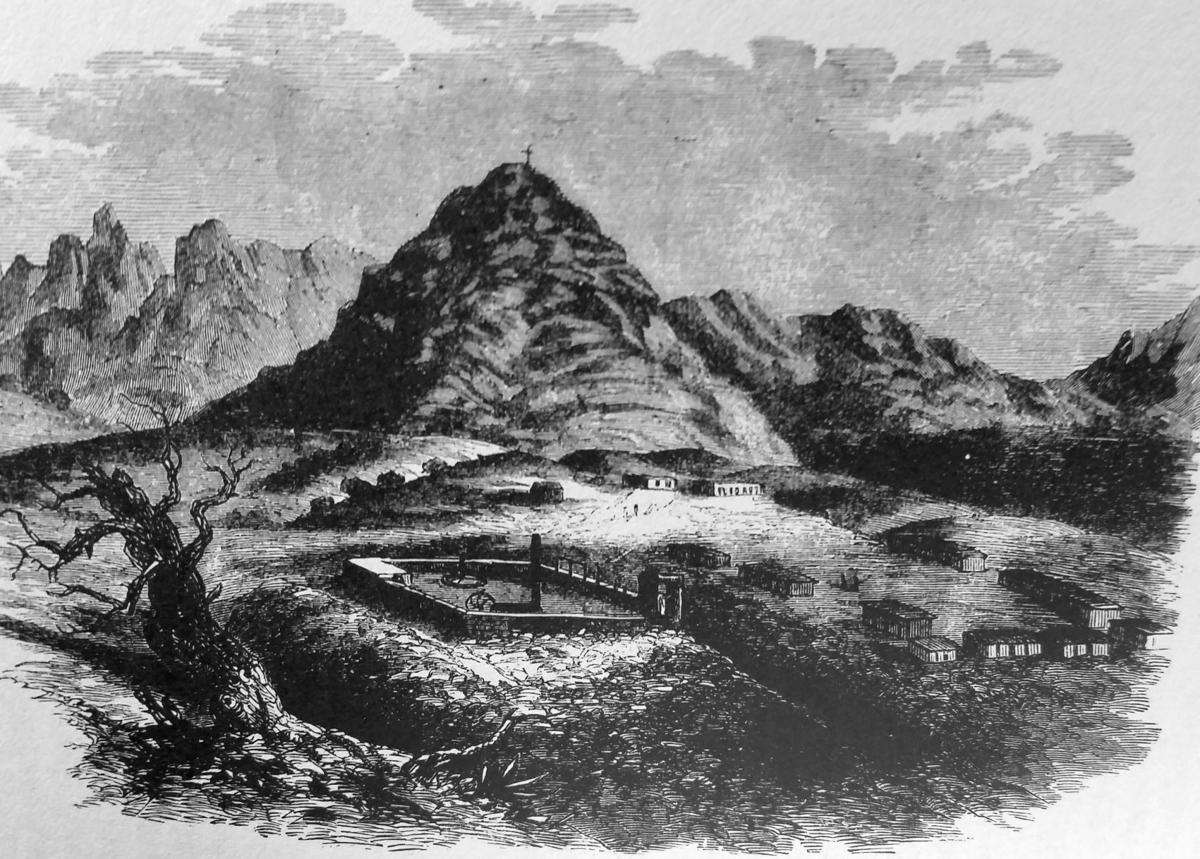

The nearby town of Cerro Colorado consisted of adobe buildings and storehouses. The mine entrance, or adit, was protected by a walled fortification that included a lookout tower used to protect the workings. Poston, managing agent for the Sonora Exploring and Mining Co., and Frederick Brunkow, geologist, mineralogist and mining engineer, used Tubac as their headquarters and actively sought new mining claims.

Poston operated a quasi-government circulating his own paper currency, “boletos,” consisting of animal depictions on cardboard that was redeemable in silver bars. He referred to his operation as a “community in a perfect state of nature.”

The Cerro Colorado Mine was also known as the Heintzelman Mine, named after Samuel P. Heintzelman, first president of the Sonora Exploring and Mining Co.

Located in the foothills of the Cerro Colorado Mountains, the mine early on produced $5,000 to $8,000 of silver per ton.

Ore was transported by wagon to Guaymas, Sonora, and later shipped by schooner to San Francisco paying over 50 percent dividends. Some ore was also shipped by wagon over the Santa Fe Trail to Kansas City as a sample to eastern investors of the potential mineral wealth found in Arizona.

Mineralogist and topographical engineer, Ehrenberg described the Heintzelman vein as one of the richest yet discovered in the world. Brunkow assayed ores from the 60-foot level and determined they contained 1,000 to 4,000 ounces of silver to the ton.

About 120 Mexican miners were employed at the Heintzelman Mine earning 50 cents to a $1 a day. A small adobe furnace was built at the site in 1858 at a cost of $250. Roughly 22,800 pounds of ore subsequently smelted produced 2,287 ounces of silver and 300 pounds of copper.

Remnants of arrastras and whims, the devices similar to a windlass used to haul ore to the surface, lay scattered about the mine when John Ross Browne visited the site in 1863. The main shaft was sunk down 140 feet though part of it was submerged by water.

Samuel Colt assumed presidency of the Cerro Colorado Mine in 1859. Production at the Heintzelman Mine was recorded as $100,000 that year.

However, this did not include the stolen ore shipped to Mexico, which some estimate at $900,000.

Known later for his Hartford arms manufacturer of the Colt revolver, he claimed “the mine was but a hole to bury money in.”

This was after the high-grade surface ore had been removed and the technological conundrums of processing the lower-grade ore below became evident having to rely on the barrel amalgamation process.

Incessant theft and desertion forced John Poston, brother of Charles, to execute the guilty parties beginning with a Mexican foreman, Juanito, caught transporting silver bullion to Mexico from the mine illegally. Rumor continues to this day that Juanito had buried $70,000 of the stolen silver bullion near the mine.

John Poston, along with two German miners, was murdered at the mine by Mexican outlaws.

The buildings and equipments around the mine were destroyed by Apaches after the U.S. military abandoned the area during the Civil War.

During the 1960s, surrounding claims, including the Silver Shield Mine and Silver Queen, later went through a succession of ownership, including Tucson merchant and Pioneer Hotel owner Harold Steinfeld and Walter Bopp.

The mill, composed of six flotation cells, did accept ore trucked in from the Arizona Mine near Ruby for processing. Although, dewatered, structurally retimbered and worked by drifting, the ore was too low grade to mine at a profit.

Perlite was also discovered in the Cerro Colorado Mountains and described as “dark gray to pinkish-gray stringers of perlitic glass” in rhyolite.