Tamara Khachatryan had pulled her then-4-year-old daughter out of school in Syria by March 2012. Life in their war-torn country was too dangerous.

But on Mother’s Day the teacher implored her to let Angelina take part in the festivities. It won’t take long, she promised.

Two hours, three hours, four hours passed. Her daughter still wasn’t home.

Finally, Khachatryan saw a small school bus crammed with children pull up to her building. Teachers were scrambling to get everyone back to their parents.

Government forces or rebels — Khachatryan doesn’t know which — had parked a car full of explosives in front of Angelina’s private Christian school.

On the wall, they scrawled their message: “Today every mother will cry.”

As the fighting escalated with bombs going off near their neighborhood and exchanges of gunfire right below their second-floor apartment — Khachatryan, 35, and her husband Fadi Iskandar, 42, knew it was time for them to leave. She had a tourist visa for the United States; he would follow later.

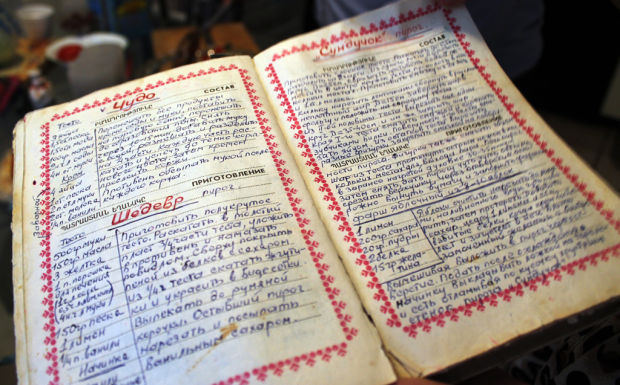

On Aug. 12, Khachatryan grabbed a suitcase, a cookbook her aunt had written by hand under candlelight more than 20 years before and her violin — her most prized possession. Then she took her frightened daughter by the hand and led her to a new life — first in Los Angeles, and ultimately in Tucson.

More than 100,000 Syrians have been killed and millions more have fled since unrest and violence began more than two years ago with peaceful protests against the regime of President Bashar Assad.

The government responded with a fierce crackdown, and the situation continues to devolve with Iranian-backed Hezbollah militants fighting with the government and Al-Qaida affiliates fighting with the opposition, said Leila Hudson, director of graduate studies in the School of Middle Eastern and North African Studies at the University of Arizona.

“Moderate, secularist forces are resource-deprived and organizationally weak,” Hudson said. “The longer the fight goes on, the more extreme it will get.”

More Syrians are now forcibly displaced than people from any other country, the United Nations reports.

The vast majority fled to surrounding countries, but a growing number are seeking refuge farther away, including the United States.

Asylum applications here have soared in the last couple of years, from 36 in fiscal 2010 to more than 1,000 so far this fiscal year, data from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services show. People can also seek asylum before an immigration judge, as a defense against deportation, but those numbers are very small for Syrians.

Homeland destroyed

From afar, Khachatryan and Iskandar have watched their homeland be destroyed.

More than half of their country’s hospitals are damaged or wrecked.

Government forces and opposition groups alike have used schools as military bases, barracks, detention centers and sniper posts, the United Nation’s Children’s Fund said. At least 1 in 5 Syrian schools no longer functions as a place of learning, with thousands of them destroyed, damaged or sheltering people fleeing from violence, the fund reported.

Muhammad Al-Khudair, who left Syria three years ago to study at the University of Arizona, said his neighborhood in Homs was literally flattened.

Since the fighting started he’s been glued to Facebook, following every development.

Even when he knew the situation was bad, every time he called his parents in Homs, they would say, “Nothing is going on; everything is OK.”

They were afraid to speak, Al-Khudair said.

His parents fled to Saudi Arabia, where he has two siblings, but he still has friends and family members in Syria.

Since the conflict began, he has lost 11 people, from acquaintances to extended relatives.

After nearly three years of fighting, he said, people have gotten used to the thud of artillery shells, the rumblings of mortar attacks, the drone of warplanes overhead. “They say, ‘It’s only shootings’ or, ‘It’s only mortar.’”

Even so, he remains hopeful he’ll be able to return home one day.

“I have to go back. I belong to that country,” said Al-Khudair, who is earning a master’s degree in Middle Eastern studies. “I dream it’s going to be a free country, a much better country.”

“No way to come back”

Khachatryan and her husband aren’t as hopeful.

Khachatryan, originally from Armenia, moved to Syria in the late 1990s to teach music at an institute where she met her now-husband.

They traveled the world together, performing with international singers. Iskandar even performed in Phoenix in the early 2000s.

“We’ve been to many places in the world and never think to live in another country,” Iskandar said from their two-bedroom apartment in the north side.

In their hometown of Aleppo, Syria’s commercial capital and wealthiest city, they never got involved in politics.

Even after the conflict started in other parts of the country, he said, “I only think about how we can live a good life.”

When Khachatryan was packing her bag, they didn’t think it would be permanent. Mother and daughter would come back when life in Syria returned to normal.

But things just kept getting worse. Extremist Islamists took control of parts of the north, at times targeting Christians, they said.

“Syria, before this, was always — politically, culturally and socially — a place of religious diversity and tolerance,” said Hudson. “But the more the Islamic extremists enter into the play, the more we have seen the rise of intolerance on the ground.”

Those who could, left.

“This one went to Germany,” Iskandar said pointing at a picture of fellow musician as he goes through old photographs on a laptop. “He is in Sweden … he went to Australia.”

His elderly mother and two siblings remain in Aleppo, where phone lines and Internet connection are spotty. Electricity can be off for days. Prices for basic staples have quadrupled.

Bombs, missiles and tank shells have battered large parts of the country. “Now we don’t have the same country, and I think there is no way to come back,” he said. “I think Syria finished.”

Since they arrived in Tucson, where Iskandar has a cousin, the couple have focused on their music.

Back in Aleppo, they had a library full of sheet music collected over their lives — both started playing the violin as children. Before fleeing, Iskandar scanned as many precious pages as he could and downloaded videos of their concerts into an external hard drive.

As soon as he got his work permit earlier this year, he started to play at Five Palms Steak & Seafood restaurant six days a week.

The couple play at church services, museums and benefit concerts. Khachatryan also is practicing for an audition to join the Tucson Symphony Orchestra. “We want to do the best we can do,” said Iskandar. For them, music is a big part of that.

“If I stay home I get angry and think of everything that happened,” said Khachatryan, who is expecting the couple’s second daughter.

“It’s not easy, I can’t forget everything we lived, but I try to begin a new life to do music.” And they continue to pray for the war to end. “Every day we pray for Syria. That’s the only thing you can do. We can’t do anything else.”