In one section of its new rules protecting washes and streams, the Environmental Protection Agency says it will narrow the scope of regulation.

In another section, the EPA says it’ll slightly increase the number of rivers, streams and washes eligible for regulation.

Opponents of the new rules say this is contradictory; EPA officials insist it isn’t. But it is a sign of the confusion and complexity that has heightened the controversy over the new rules, published by the EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers in the Federal Register on Monday.

Last week, Arizona joined 12 other states in filing a lawsuit — one of three filed by a total of more than 20 states — against the rules. The National Association of Home Builders, of which Tucson’s Southern Arizona Home Builders Association is a member, filed a similar suit Thursday.

Developers, farmers, ranchers and other businesses call the rules federal “overreach.” Environmentalists say they ensure that rivers and washes remain ecologically whole and aren’t polluted.

Yet some environmentalists aren’t thrilled at some of the new rules, particularly those that continue to allow mine tailings and other wastes to be put into certain water bodies without treatment.

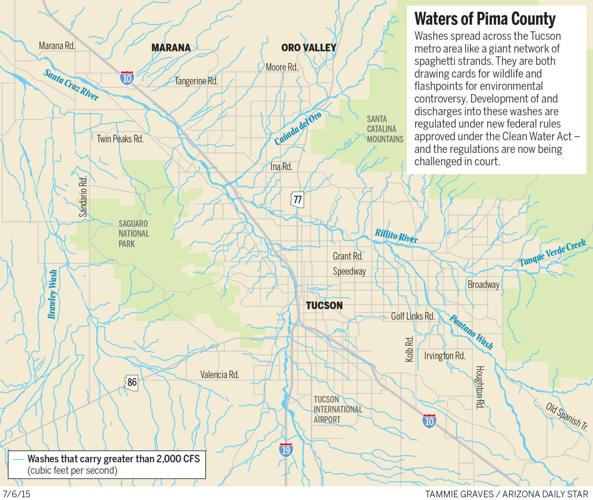

The rules have a particularly strong impact here because they cover ephemeral washes — those that stay dry most of the year. Most streams and washes in the Tucson area are ephemeral.

Here are some questions and answers about the new rules:

Q. Why do they matter?

A. In Arizona, the rules’ most obvious impact falls on developers of new subdivisions, shopping centers and mines. If construction requires the discharge of fill material into a federally protected wash, the businesses must obtain a permit under the federal Clean Water Act. Such requirements have been in place since the Clean Water Act passed in 1972. But U.S. Supreme Court decisions in 2002 and 2006 narrowed the federal government’s authority in these areas. The new rules were enacted to respond to these rulings.

Q. How can the rules limit the scope of protection and expand the number of washes covered at once?

A. The EPA narrowed its scope by limiting how far certain water bodies can lie from navigable rivers and be covered, said Ken Kopocis, acting administrator of the EPA’s water office. To be covered by the rules, a wetland must lie within a 100-year floodplain of a navigable river or 4,000 feet from a high tide line or ordinary high-water mark of a navigable river. Before, distance didn’t matter.

But EPA predicts the total number of rivers and washes covered will increase 2.84 to 4.65 percent nationally, compared to the period 2009 to 2014. Then, the guidelines agencies used to carry out the Supreme Court’s rulings were so unclear that they resulted in fewer washes being covered than should have been, Kopocis said in an interview.

Q. What do opponents say about this?

A. This is a contradiction, says the lawsuit filed last week by Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi. The new rules will require states to establish water quality standards for miles of newly regulated ephemeral streams, ponds, prairie potholes, wetlands and ditches, the lawsuit says. State governments will also be forced to deal with significantly more applications for various permits to discharge pollutants and ordinary fill into washes, the lawsuit filed by Arizona and 12 other states says.

Q.Why are ephemeral streams covered?

A. “The science told us that you can’t protect larger bodies of water if you can’t protect the features leading to them,” Kopocis said.

EPA said its analysis of more than 1,200 peer-reviewed studies found “unequivocally” that streams, regardless of how big they are or how often they flow, are connected to and strongly influence how effectively downstream navigable waters function.

Q. Why is this controversial?

A. The new rules protect lesser streams with a significant connection to a navigable river or stream. But legally, the agencies exceeded their authority under the Clean Water Act and the earlier Supreme Court rulings by including all such water bodies, Arizona and other states filing suit say.

“The one-size-fits-all nature of the rule fails to take into account Southern Arizona’s unique environmental attributes,” said Patrick Ptak, communications director for U.S. Rep. Martha McSally of Tucson, who opposes the rules.

“The rules rely upon vague criteria without considering, for example, how far a wash is from a navigable source of water or how often it even fills with water,” Ptak said. “For a rancher or small business owner wondering whether they now face federal regulation due to this expansion, this can be a problem.”

Q. What about the mine waste rule?

A. The EPA left in place an exemption that in some cases allows certain water bodies to have mine tailings, farm wastes and other wastes placed in them without treatment or protection from the Clean Water Act.

The Tucson-based Center for Biological Diversity and the Waterkeeper Alliance said in a written statement: “The final rule fails to protect streams and rivers that have historically been protected under the Clean Water Act, exempting industrial-scale livestock facilities, and allowing streams and rivers to be impounded or filled with toxic coal ash and other waste.”

The EPA said a mining company still must apply for a permit to build the impoundment, but requiring permits to put waste into them defeats their purpose because that would force companies to treat the wastes in advance. The wastes are supposed to be treated naturally in the impoundments, by allowing solids in them to settle or to have them gradually become less acidic.

Q. Tributaries are a flashpoint in this dispute. Why?

A. The new rules for the first time defined what kinds of tributaries are covered. They must have a clearly defined bed and bank and an ordinary high-water mark. They must also contribute water to a navigable stream or a water body that crosses state lines, among other rules.

The lawsuits filed by Arizona and other states say classifying all such tributaries as protected waters exceeds the federal government’s authority under the Clean Water Act, and goes beyond what the Supreme Court has allowed. Other legal observers have noted that a key justice in the 2006 Supreme Court ruling, Anthony Kennedy, didn’t like the tributary definition that the EPA just adopted.

The EPA’s Kopocis, however, predicts the new tributary definition “will have virtually no effect” on the number of washes protected in the Southwest or nationally.