The aftermath of a confrontation at the University of Arizona has brought protests, threats of violence, criminal citations for three students and international media attention.

The confrontation came March 19 while two Border Patrol agents spoke to a student-run club for criminal-justice students. Several students in the hallway outside the classroom called the Border Patrol an “extension of the KKK” and then chanted “murder patrol” as the agents walked out of the Modern Languages Building and drove away.

Since a video of the incident went viral, three students were issued misdemeanor citations by UA police for interfering with the peaceful conduct of an educational institution. Two of the students, Mariel Alexandra Bustamante, 22, and Denisse Moreno Melchor, 20, who also was cited for threats and intimidation, issued a written statement Thursday saying they were facing a “backlash” that has been “overwhelming and violent.”

“There is much anxiety and fear due to death threats against those who are directly impacted and those who have aligned in solidarity,” they wrote.

UA police cited a third student Thursday while working a vehicle collision, according to UA spokesman Chris Sigurdson. Among the onlookers of the wreck, the officers recognized Marianna Ariel Coles Curtis, a 27-year-old graduate student, from the video of the March 19 protest. Officers asked her to come to the station, where she was cited and released.

Elsewhere on campus, the Mexican American Studies faculty notified the university on Tuesday of a threat and some offices were closed briefly as a precaution, Sigurdson said. The offices were reopened after UA police, along with other law enforcement agencies, “evaluated the message and the source of the message and determined there was not a threat to campus or to public safety.”

On Wednesday, a group of UA faculty members writing as “Professors of Color, UA” denounced the criminal investigation of the students as a “draconian response to the peaceful protest.” The students were exercising their First Amendment rights and the university should end the UAPD investigations and “harassment” of the students, they said.

The professors said the student club that invited the Border Patrol agents was “putting the safety of undocumented students, staff, and faculty at risk by inviting armed and uniformed CBP agents on campus.”

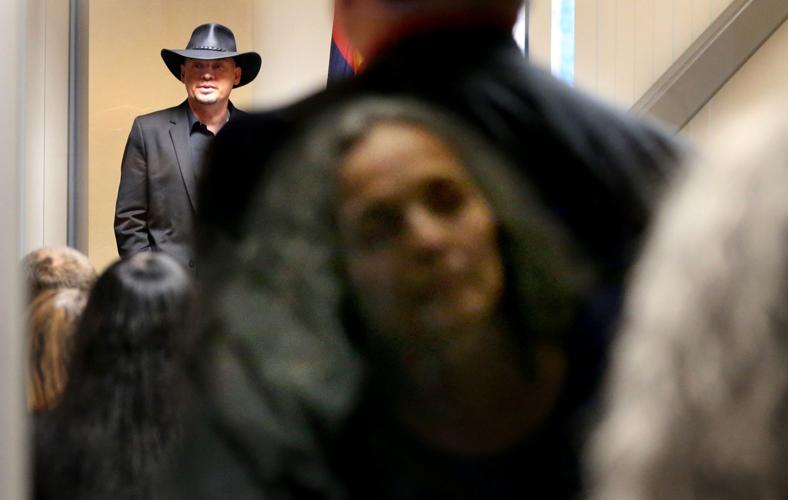

On Thursday, dozens of students wearing T-shirts with “U.S. Murder Patrol” on their chests silently lined the hallway outside a meeting of the UA chapter of the College Republicans at the Student Union. On their backs, they pinned the names of people killed by Border Patrol agents or who died in custody.

Inside the meeting of about 30 students, Art Del Cueto, a Border Patrol agent and head of the local union chapter of the National Border Patrol Council, said the protesters from the March 19 incident stifled productive communication.

“Are you ever going to get a question out if I’m just talking over you and keep yelling?” Del Cueto said.

When asked how students could engage with each other in light of the ongoing controversy, Del Cueto said, “I think you’d have to talk more to the individuals on the outside (of the meeting room) than the individuals on the inside because I haven’t seen any of these individuals chastise or hold up signs and attack anyone on the outside.”

Also on Thursday, dozens of Arizona State University students marched in support of the UA students cited by police and protested the presence of border agents on their campus at a career fair, the Arizona Republic reported.

In response, UA officials are planning to hold a series of campus discussions about free speech.

“Following the publicity surrounding protests against the Border Patrol for being on campus, students, faculty, staff and others on both sides of the issue have been targeted with hateful emails, social media posts and, most concerning, threats from external organizations and people who are not part of the University,” UA President Robert C. Robbins wrote Wednesday in a letter to the campus community.

Meanwhile, the story of the confrontation appeared in The New York Times, the Washington Post, the Chronicle of Higher Education, even the British newspaper The Guardian. It also has appeared in dozens of online conservative and far-right news outlets.

In their statement, Bustamante and Moreno said they “have recently become national news items simply because we would like to be able to study on a campus that prioritizes the safety of its students.”

They noted the UA sits on the traditional lands of the Tohono O’odham and the university recently was designated as a Hispanic-serving institution.

Activist Isabel Garcia is reflected in the glass as she looks into a closed meeting of the UA College Republicans involving a talk by local Border Patrol union chapter leader Art Del Cueto, background. Students lined the hallway outside the meeting.

“The presence of Border Patrol on campus is harmful to students for many reasons,” they wrote. Agents “perpetuate violence upon and criminalize Brown, Black and Indigenous communities.”

They wrote that “families have been taken from their homes, on routine stops, and on the street.” Border Patrol agents also have “shot and killed people and children with impunity, crimes that have gone unpunished. The criminalization of these communities is solidified by Border Patrol’s presence on our campus.”

It was “alarming” that the UA “seems to be responding to pressure” from Del Cueto, who called for the UA to investigate the students shortly after the video went viral, they wrote.

Del Cueto’s talk to the College Republicans was billed as a broad discussion of border security, rather than a response to the campus controversy. After speaking generally about the national conversation regarding border security, he fielded questions from students for nearly an hour.

One student noted a certain level of distrust that comes from police unions protecting corrupt officers and asked how the Border Patrol oversees agents. Del Cueto said he defends agents, but “I do not condone bad behavior.” With egregious actions, he sometimes tells agents “you’ve got to take your licks” or “their best bet is to retire.”

A student from Laredo, Texas, which is also on the U.S.-Mexico border, asked whether hostility toward agents comes from people who do not live on the border.

Del Cueto said Texas is “completely different than it is here.” In Texas, local residents support agents and he doesn’t have to worry about restaurant employees spitting in his food. When he is in uniform in Arizona, he only eats at restaurants where he can watch his food be prepared.

A student asked if the Border Patrol had an official policy when it comes to destroying humanitarian aid, such as videos of agents destroying water jugs left for illegal immigrants crossing in the desert. Del Cueto said agents who were caught destroying aid supplies were “severely disciplined.”

The same student asked about criminal charges brought against aid volunteers in Tucson’s federal court, saying the “charges seemed a little bit ridiculous” and asking how aid volunteers can “make sure they can do their activism without breaking the law.” Del Cueto said he learned about the cases in his capacity as a law enforcement officer and couldn’t comment.

Amid the campus controversy, Del Cueto encouraged students to engage with each other one-on-one, rather than in groups or when people have an “entourage.”

“Following the publicity surrounding protests against the Border Patrol for being on campus, students, faculty, staff and others on both sides of the issue have been targeted with hateful emails, social media posts

and, most concerning, threats from external organizations.” UA President Robert C. Robbins, in a letter to the campus community