Growing up in downtown Tucson and the south side, Bertha Sanchez was an irregular visitor to the Santa Cruz River in the days that it carried water. Matt Perri, who grew up in Menlo Park west of the river, saw it several times a week.

Today, their reactions to the prospect of water running downriver again are also different, with Sanchez receptive to the idea and Perri turned off by it.

Sanchez, born in 1932, spent her childhood on Alameda Street downtown, and moved with her family to the south side at age 14. She remembers crossing over the river as a child with her family, seeing it as attractive and fun to look at: “Sometimes it would be slow-running, all of a sudden it would be fast-running, but I never went in. I guess I was afraid of the water.”

Living on the south side in the 1940s and ’50s, she recalled, “My dad had an old car; he would take us just to go visit and see if there was any water. Sometimes there was water. Sometimes there wasn’t.”

She also has a vivid memory of the river from October 1983, when the river’s worst flood in modern history delayed her grandaughter’s baptism for two days. By then she was living in Menlo, and her daughter and her 4-month-old granddaughter were living on the southeast side, planning to drive on Oct. 1 to have the child baptized at St. Margaret’s Catholic Church on Grande Avenue. But the river was overflowing at Congress Street and they couldn’t get over via the bridge. So they had to come two days later after the floodwaters receded.

Perri, like Sanchez now in his 80s, moved to Menlo in 1946 with his family when he was 9, and when “it was pretty much in the country at the time,” he recalled.

When Perri was 12, he would walk his family’s two goats — one of each sex — down to the river a few times a week to feed off its low-lying grasses, and occasionally saw water there, he said.

“When the river flowed; it flowed for a couple of days. It would be quite an event. People would go out and have picnics down there. They would bring their families.

“Since there was no river bank, it would flow without any boundaries. We would see big waves of water flow. You could hear the frogs at night.”

He also remembers walking to the river, seeing ponds and occasionally watching ducks fly by. He had a slingshot rifle, and he would do target practice down there, shooting at “birds, rabbits, anything.”

Perri, now a real estate broker, left Tucson in 1961 and returned in 1980. That year, he watched city work crews start dredging, digging and grading the river to line it with soil cement to protect its banks from erosion.

Its purpose was flood control to make possible the future development of the long-planned, long-delayed Rio Nuevo west-side redevelopment project, a project that Bertha Sanchez dismisses as “Rio Nada, because there’s really nothing there (on the west side).”

“They were cutting down the trees. I saw them up in the trees, with chainsaw; cutting branches and stumps that would hit the ground, hit sandy bottom,” recalled Perri, who had unsuccessfully fought the soil cement project when proposed. “It would break my heart. I went berserk challenging them to no avail, seeing them cut all these cottonwood trees.”

He acknowledged the cement lining probably saved his neighborhood from flooding in the same October 1983 deluge that delayed Sanchez’s granddaughter’s baptism. But he doesn’t think the city has made the most of the river as a recreational opportunity.

“A river is the heart of any city. Usually rivers are enjoyed and appreciated and without channeling them, like they did here,” he said. “It still is an eyesore. The city, with all the money and time, it has never done anything to improve the river scene at all.”

Today, Sanchez doesn’t miss the river water, since she never spent much time in it. But she’s open to the idea of releasing reclaimed water, saying, “Everything is so dry in that area. I’d probably go and stick my feet in there now.”

Perri dismisses the city’s plan as tokenism.

“It’s not a very sincere gesture. The excess water that’s already being dumped upriver, they want to bring it down over here, to try to make this eyesore a little bit wetter or greener,” he said. “It’s sad, a lost opportunity. It doesn’t look like a river anymore; it looks like a big trench, just a big ditch that goes through the neighborhood.”

30+ historic photos of the Santa Cruz River through Tucson

Waterfalls on the Santa Cruz River in 1889 near Sentinel Peak in Tucson.

Girls in Santa Cruz River,1889-1890.

A bridge over the Santa Cruz River near Sentinel Peak in Tucson washed out during flooding in 1915.

Santa Cruz River at St. Mary's Road bridge in 1931.

The Santa Cruz River flows north as seen from Sentinel Peak in Tucson in the early 1900's.

El Convento along the Santa Cruz River, ca. 1910.

Flooding of the Santa Cruz River, Tucson, in September, 1926, from “Letters from Tucson, 1925-1927” by Ethel Stiffler.

Flooding of the Santa Cruz River, Tucson, in September, 1926, from “Letters from Tucson, 1925-1927” by Ethel Stiffler.

Aerial view of the Santa Cruz River as it winds its way through Pima County north of Cortaro Road in 1953. The county was considering a bridge at several locations, but had to contend with the ever-changing course of the river.

The Tucson Citizen wrote in 1970, "The Santa Cruz River is a garbage dump" and "even marijuana grows in it." City leaders were pushing to upgrade and beautify the channel. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was studying the possibility.

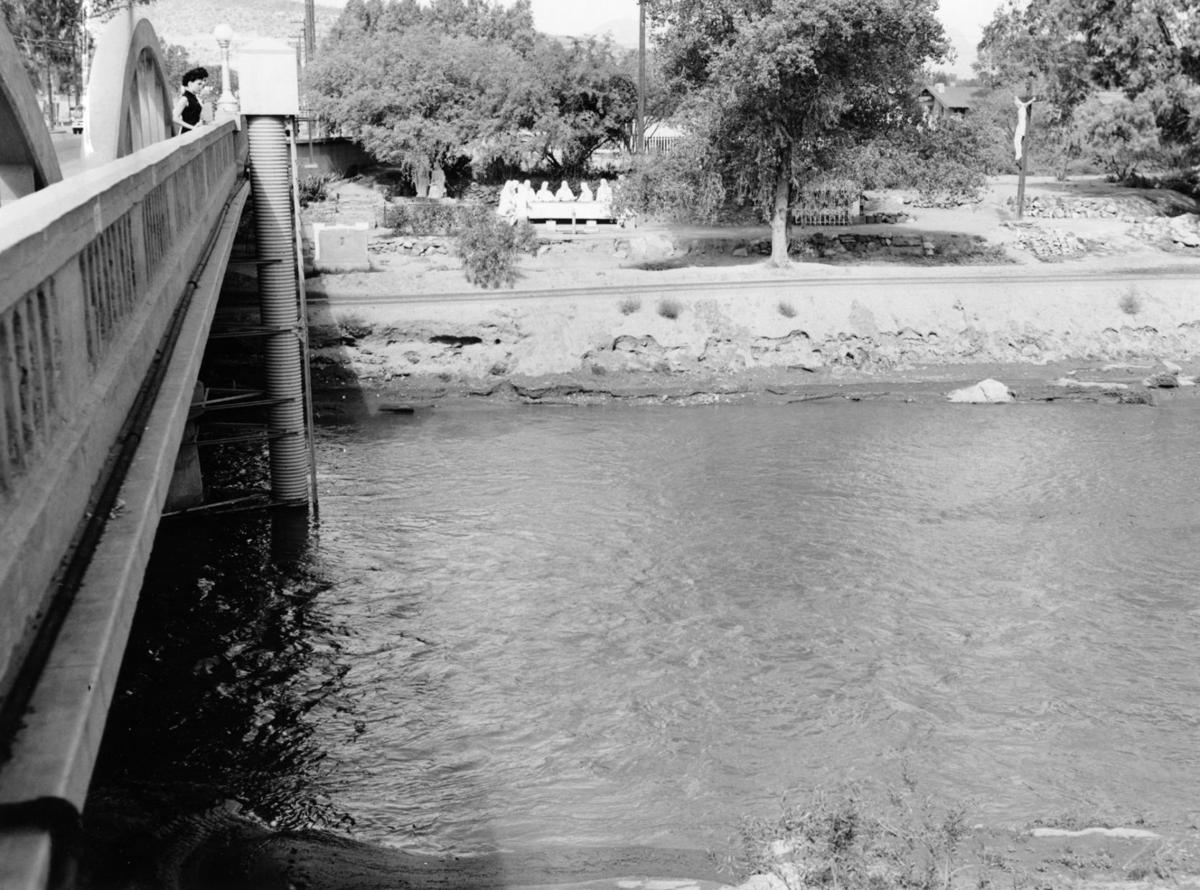

The Santa Cruz River flowing under the Congress Street bridge in August, 1952. The Garden of Gesthemane is in the background.

By July 24, 1970 the old bridge on West Congress over the Santa Cruz River had to go and be replaced by a new bridge.

By July 24, 1970 the figures from Felix Lucero's Last Supper had been on the west side of the Santa Cruz River for more than 20 years. City authorities had decided to leave it in place while a new bridge on West Congress Street was to be replaced.

Volunteers from the Tucson Jaycees and Junior Chamber of Commerce finish restoration of the statues and grounds of the Garden of Gethsemane along the Santa Cruz River in May, 1964. The statues were ravaged by vandals and weather. The city parks and recreation department worked with the volunteers. Artist Felix Lucero began sculpture project in 1938 and finished it nine years later.

Drought in June, 1974, turned the Santa Cruz riverbed into crunchy chunks of dried mud.

The Santa Cruz River flowing under Silverlake Road in August, 1970.

Children play in the Santa Cruz River near Speedway Blvd in August, 1970.

The Santa Cruz riverbed at Congress Street in November, 1967.

After years of waiting, crews began clearing debris and channeling the Santa Cruz River in November, 1977, and constructing what would become a 14-mile river park. The Speedway Blvd. bridge is in the background.

After years of waiting, crews began clearing debris and channeling the Santa Cruz River in November, 1977, and constructing what would become a 14-mile river park.

The Santa Cruz River looks peaceful flowing underneath Speedway Road after days of flooding in October, 1977.

Adalberto Ballesteros rides along the Santa Cruz River west of downtown Tucson in 1980.

The Santa Cruz River looking north from Valencia Road in July, 1974.

Junked cars and trash spill into the Santa Cruz River, looking south, just south of Grant Road in July, 1974.

Road graders scrape the Santa Cruz River channel between Speedway and Grant roads during bank stabilization construction in May, 1991.

Water surges in the Santa Cruz River at the St. Mary’s Road bridge on Oct. 2, 1983.

Flooding in Marana after the Santa Cruz River overflowed its banks in Oct. 1983.

A bridge on the Santa Cruz River northwest of Tucson washed out during flooding in October 1983.

Residents watch the surging Santa Cruz River rush past West St. Mary's Road on January 19, 1993.

Tucson firefighters are standing by and waiting for two kids floating in the Santa Cruz River on some type of object during flooding in July, 1996.

As the Tucson Modern Streetcar rumbles across the Luis G. Gutierrez Bridge, water flows bank to bank along the Santa Cruz River after a morning monsoon storm on July 15, 2014.

Johnny Dearmore skips a rock in the Santa Cruz River as reclaimed water is released into the channel at 29th Street as part of the Santa Cruz River Heritage Project on June 24, 2019. The release of effluent is the city’s first effort to restore a fraction of the river’s flow since groundwater pumping dried it up in the 1940s.

The Santa Cruz River flows Friday morning July 23, 2021 after an overnight monsoon storm passed over in Tucson, Ariz.

Betsy Grube, center, with Arizona Game and Fish Department, releases longfin dace fish into the Santa Cruz River at Starr Pass Boulevard on March 23, 2022, as Mark Hart, right, takes a video and Michael Bogan, a professor in aquatic ecology at the University of Arizona, picks up more fish to release. The 600 fish were captured from Cienega Creek in Vail.