For traditional worshippers in a remote Tohono O'odham village, the 25-mile trip to a sacred site across the border is about to turn into a trek of more than 70 miles.

The U.S. Border Patrol plans to seal Menager's Dam Gate, a cattle crossing Ali Jegk, Ariz. residents such as Ofelia Rivas have used all their lives to reach a ceremonial site in Quitovac, Mexico, and to visit tribal members who live south of the border.

The tribe asked the Border Patrol for a vehicle barrier to stop the cars and trucks that illegally barrel through the open gate at all hours. The decision, tribal officials say, was unfortunate but necessary to protect public safety.

Standing along the international line directly behind her home, Rivas, 50, points to wooden stakes painted pink and marked with green tape, demarcating roads the U.S. government uses to monitor the area. One stake is steps from the gravesite of a migrant woman and her young daughter that Rivas and her relatives have tended since the 1960s. On All Souls' Day, Rivas sets places for them at her dinner table.

N0 MORE CROSSING: This broken-down truck was to be driven illegally across Menager's Dam Gate on the Tohono O'odham Reservation in 2006. At the tribe's request, a vehicle barrier will go up later this year.

For the nearly 12 million people who live along the U.S.-Mexican border, the line is an unnatural divider, splitting cultures that are otherwise alike. Sealing the border would forever divide communities and tribes whose strong cross-border ties are integral to their identities, a Star investigation found.

In border towns such as San Luis and Nogales, Ariz.; Calexico, Calif.; and Sunland Park, N.M., Spanish is as common as English. Families and friends travel back and forth, especially American youths lured by the music and discothèques in the bigger cities on the Mexican side.

When barriers go up, travel time can stretch from minutes to hours. But border fencing doesn't close legal immigration channels and therefore shouldn't be viewed as culturally divisive, says Joe Kasper, an aide to U.S. Rep. Duncan Hunter, R-Calif., a longtime advocate of border fencing.

For five generations, Monica Rubio's family has lived in Jacumba, Calif. Rubio, with daughter Christina, left, and niece Marivel Gallego, used to be able to walk across the border and visit relatives in Jacumé, Mexico. She no longer can do so.

Jacumba

From his ranch house just east of Jacumba, Calif., 58-year-old Raúl Gallego can see his parents' house in Jacumé, Mexico, across the rolling green hills.

He and his wife, Monica, 50, used to walk 20 minutes or drive 10 minutes across the border two or three times a week. After his parents died, he and his wife continued to make weekly trips to check on their house.

But in the post-Sept. 11 world, border security trumps convenience and tradition. Border Patrol agents no longer allow crossings at Jacumba. The Gallegos and others who came and went there now must drive 40 miles west to the Tecate Port of Entry. It takes an hour and 15 minutes to get there and up to four hours to get back, they say.

"It's just made everything different," Raúl Gallego says. "It hasn't done anything good for the community."

Jacumé residents used to walk two miles to the Mountain Sage Market in Jacumba each morning for fresh food unavailable in Mexico, such as bread, milk and eggs, says Norma Jean Espinoza, the market's owner.

On Halloween, the Mexican children would trick-or-treat in Jacumba. Jacumbans would go to Mexico for the rodeo or barbecues. Many lived on one side and worked on the other. Even more than other sister cities on the border, Jacumba and Jacumé were joined at the hip.

Their separation has been painful. Some families still have their picnics. Those who live in Mexico sit on one side of the shoulder-high fence. Those who live in the United States sit on the other.

At first, Border Patrol agents who knew the residents of the town of 500 would let the older women cross to buy food, locals say. But, eventually, they stopped that, too. They added corrugated-steel fencing and erected vehicle barriers.

"I don't think it was necessary to stop the Mexicans from coming over here, but I do believe in border security," says Jacumba resident and World War II veteran Norman Blackwood, 76. "It isn't so much the Mexicans I worry about — it's people from other countries."

Separated: For two years, Nelly Arrizon, left, has seen her 23-year-old son, Roger, only through the border fence between her side in Calexico, Calif., and his side in Mexicali, Mexico. More fencing and stricter security represents an inconvenience for many border communities whose residents are used to a short, direct route between towns in the U.S. and in Mexico.

Sister cities

Visit any of the sister cities along the border and as day turns to night, the same thing happens. The Mexican side lights up, the American side quiets and the most audible sound north of the border is festive music from the south.

That's true in San Ysidro, Calif., across the border from Tijuana. Growing up there, Monica Hernandez remembers Friendship Park, the westernmost tip of the international line, which was dedicated by first lady Pat Nixon in 1971.

San Diego's Save Our Heritage Organisation tells how, after a tree planting and a formal ceremony, Nixon ordered a section of the barbed-wire border fence cut, saying she hoped the barrier would not be up for too long. Then she embraced and kissed the Mexican children clamoring for her attention.

The park's name changed to Border Field State Park at the onset of Operation Gatekeeper in the early 1990s, when the U.S. government began its border-tightening strategy in the San Diego Sector, which now includes 40 miles of fencing.

The biggest influence has been psychological, says Hernandez, 31, who works for Casa Familiar, a nonprofit agency that focuses on community development and family services for Latinos.

During the 1990s, military trucks, helicopters and tractors moved into the area around San Ysidro, a 4,700-resident enclave of San Diego. It took longer to get through the border to her native Tijuana for family get-togethers, even more so after Sept. 11.

"In San Ysidro, 60 percent of the community lives at or below the poverty level. So the fence has created an underground economy — smugglers in human trafficking and drug trafficking. Our community has changed," she says. "People should look really closely at what is happening here to see what's going to happen on the rest of the border."

REMEMBERING THE PAST: A broken wooden cross lies on a grave Ofelia Rivas tends on the Tohono O'odham Nation. A few feet away, stakes, painted pink and strung with green ribbon and barbed wire, mark the border. "It would be difficult for us to support a wall or a big fence," O'odham Chairwoman Vivian Juan-Saunders says, citing sensitive archaeological sites and the need of Mexican O'odham for transborder crossings.

Tribes

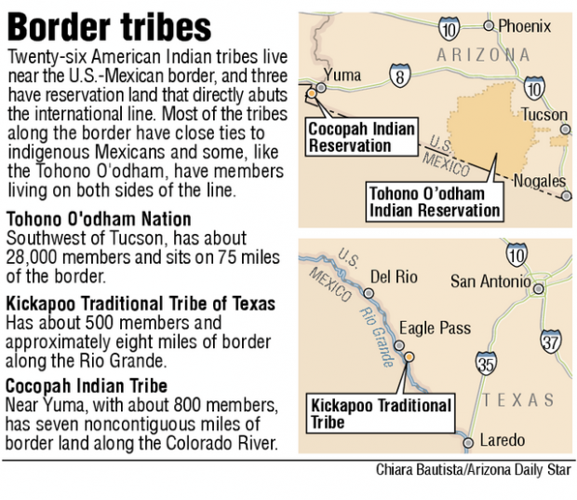

The Tohono O'odham Reservation has 75 miles of international border. It's one of three American Indian nations that sit along the international line — the others are the Cocopah Tribe, near Yuma, and the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas, near Eagle Pass. Another 23 U.S. tribes have members in the border area and often members in Mexico as well.

Indigenous people emphasize that tribal lands existed long before the border split them.

"The Earth is where God put us since time immemorial. But suddenly you can't go visit your cousin anymore," says Louis Guassac, executive director of the Kumeyaay Border Task Force in California, which advocates more open borders for the 3,500 members of the Kumeyaay Nation who live on both sides of the international line.

Four years ago, the tribe obtained renewable travel visas for several hundred of its members in Mexico to help them cross back and forth to visit friends and families. The program was modeled on one the Tohono O'odham Nation began in 1999 when it obtained renewable travel visas, known as laser visas, for 104 of its members in Mexico, giving preference to those who must visit the United States for health reasons.

The Tohono O'odham Nation has been trying to obtain U.S. citizenship for its approximately 1,400 Mexican members, similar to an arrangement the Texas Kickapoo made for a limited number of its members in the early 1980s. So far, the tribe has been unsuccessful, but talks continue, Chairwoman Vivian Juan-Saunders says.

While she stresses that most residents near Menager's Dam Gate favor the vehicle barrier for safety reasons, the tribe would oppose something more solid. Several other border cattle crossings on the reservation will remain open.

"Based on what I believe and what I've heard from our people, it would be difficult for us to support a wall or a big fence, considering the O'odham in Mexico need transborder crossings," she says. "We know there are sensitive archaeological sites along the 75-mile stretch."

Ali Jegk resident Margaret Garcia, 68, used to sleep on her porch in the hot summer, but moved inside because of Border Patrol searchlights. She's bothered by the high-speed chases and worries about her relatives in Mexico who need to travel to Sells for diabetes treatments. Like other village residents, she also worries about young tribal members who are lured by the big money of drug trafficking.

Because she was born at home and doesn't have a government-issued birth certificate, Garcia has no passport. That means in less than two years, when the government will require passports for everyone entering the country, she may not be able to visit friends and relatives in Mexico at all, she says.

Garcia and her neighbor Ofelia Rivas are two of about 25 O'odham who drive across Menager's Dam to Quitovac for an annual rebirth ceremony in July. In March, about the same number of people take a two-day spirit walk to the site as part of a ritual to bless the land.

The tribe's 2.8 million-acre reservation — the size of Connecticut — has other cattle crossings on the border that will remain open, but Rivas says they are on rough roads that are too far east of Ali Jegk to be used to go to Quitovac.

"We're going to have to behave like the illegal immigrants, sneak around so that we can get to our ceremony," Garcia says in O'odham.

Either that, or they'll have to drive from their village to the nearest official port of entry at Lukeville to get to Quitovac, a trip that's about triple the distance of their regular route.