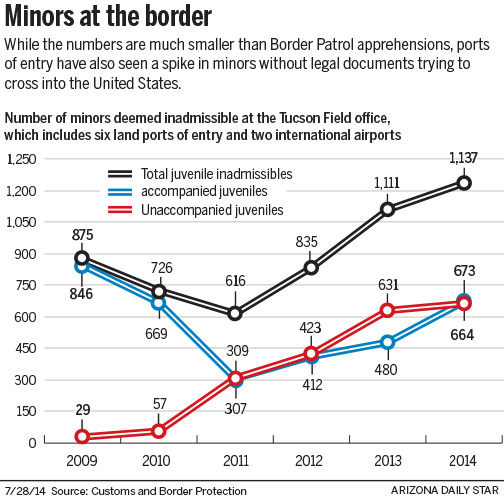

Although the thousands of unaccompanied minors apprehended by the Border Patrol continues to be a focus of concern, the number of children turning themselves in at the ports of entry has also spiked.

The number of unaccompanied juveniles deemed inadmissible by the Tucson Office of Field Operations, which includes six land ports of entry and two international airports, has jumped from 29 minors in fiscal 2009 to 664 so far this fiscal year (as of June 18), Customs and Border Protection data show.

“I’m not surprised the numbers are going up at the ports because of the way the unaccompanied minors are turning themselves in quite openly between the ports in South Texas,” said Adam Isacson, a senior associate at the nonprofit Washington Office on Latin America.

“They are not having to chase them through the scrub as they cross the river,” he said, “Border Patrol vehicles are up there and they walk up to them.”

The share of those presenting themselves through the ports of entry is still small though, compared to those who cross in between the ports. So far this fiscal year, the Border Patrol in the Tucson sector has apprehended more than 6,500 unaccompanied juveniles.

Nationwide, more than 57,000 Mexican and Central American children and youth traveling without parents or legal guardians have been apprehended by the Border Patrol so far this fiscal year. Most of them turned themselves in.

The agency has also caught more than 55,000 parents traveling with their children, but it has not provided a breakdown of how many of those are minors. Many of them are coming through South Texas, especially the Rio Grande Valley.

“We have two modes of entry: One is between the borders that is responsibility of Border Patrol,” said Gil Kerlikowske, Customs and Border Protection commissioner in a story that aired on Federal News Radio last week.

“But then we’ve had young children walking up to the bridges, walking to the ports of entry where our Customs and Border Protection officers — officers in blue uniforms — actually encounter them,” he said. “That also has required a great deal of humanitarian outreach by all of these people.”

The total extent of how many are actually coming through the ports of entry is not known. The Arizona Daily Star asked for the total number of inadmissibles broken down by gender for the Tucson area and South Texas a month ago, but CBP has not made the data available nor provided an explanation as to why it hasn’t responded to the request. An interview request with a CBP official was also denied.

Inadmissables can include people who don’t have legal documents when they present themselves at the border, have previously lied, have a communicable disease or illness or are considered to be a terrorist, said Maurice Goldman, a local immigration attorney.

In an internal CBP report from May obtained by the Star, Central American unaccompanied minors and families detained at the Rio Grande Valley asked why they didn’t surrender at a port of entry, said they had been told by others — including the smugglers — that officials wouldn’t give them a permit at the ports of entry and that they would be sent back home.

The report also said that Gulf Cartel associates and smugglers were discouraging the use of ports of entry by families traveling together as it would result in loss of income.

But some of the women recently dropped off at the Tucson bus station with their children have said the smuggler told them to present themselves at the port of entry, many of them through Douglas.

And the Guatemalan Consulate in Phoenix is recording a larger number of minors and women with their children turning themselves in at the ports of entry in the Tucson area, said Jimena Díaz, consul of Guatemala in Phoenix.

“They mostly say their parents are here and they sent for them,” she said in reference to the children. They also cite the increasing violence in their country.

The consulate interviewed 166 unaccompanied children who presented themselves at a port of entry in Texas or Arizona in April. The number jumped to 206 in May, and in the first three weeks of June they had 164 — making the largest share of all the children and youth interviewed. Those over 18 continue to cross through the desert, Díaz said.

Being taken into custody is almost seen as the right way to do it for the unaccompanied minors and women traveling with their children, said Isacson.

Although Mexicans make up about 30 percent of those deemed inadmissible at ports of entry nationwide, officials at the Mexican Consulate in Nogales, who deal with the issue of unaccompanied minors at ports of entry, said they have seen a decrease of minors coming through.

They don’t know why, except that migration of Mexicans through Nogales has gone down, they said.

Generally, Mexican children under 14 years old come through the port of entry, while older teens cross through the desert, said Adriana Alvarez, who works in the area of protection at the consulate.

“In the case of Mexican children, the families don’t want to risk their lives by crossing them through the desert,” she said. “So they have someone cross them using someone else’s documents or hiding in vehicles.”

People coming through the ports of entry sometimes claim a fear to return to their home country.

Mexican nationals who don’t have a credible fear of returning to their country can in some cases be promptly returned, but the process for Central Americans is more complex because immigration officials have to coordinate the travel documents with their governments and schedule the flight.

“And if it’s an unaccompanied child, we have international standards we have to live up to,” said Isacson. “They are treated almost like refugees, at least at first.”

Under a 2008 anti-trafficking law, children who are apprehended need to be screened to make sure they are not being trafficked or have a credible fear of returning to their home country.

When they come from countries that do not border the United States, the process usually includes being sent to a shelter run by the Office of Refugee Resettlement, where they are reunited with their parents or relatives in the U.S. while their legal immigration case is resolved — which can take years.

Mexican children under 14 years of age who present themselves at a port of entry are processed through the 2008 law and only released to their parent or legal guardian, Alvarez said, but older juveniles and those apprehended by the Border Patrol can be sent back to Mexico that same day.

The number of people coming through will depend on how well the administration’s message gets out that people will be deported if they turn themselves in, he said.

“As knowledge expands and spreads that there is in fact no special dispensation for women and children,” he said, “people may keep coming. But they will try to avoid detection and go deeper into the desert unless they have a well-documented claim.”