A craggy border canyon in San Diego is difficult to monitor and too rough to handle much of a fence, so the federal government has come up with an idea — it will fill the 230-foot-deep chasm and get the dirt to do it by lopping off the tops of two nearby mesas.

By smoothing out Smuggler's Gulch with enough dirt to fill 70,000 dump trucks, the U.S. Border Patrol expects to be able to better patrol one of San Diego's weak spots.

Its 66 border miles already have 40 miles of fence reinforced with nine miles of double fencing, seismic sensors, stadium lights, helicopters, horseback patrols and cameras.

But the number of illegal entrants trying to cross there has jumped by 26 percent in the last five years, and authorities say they need more control.

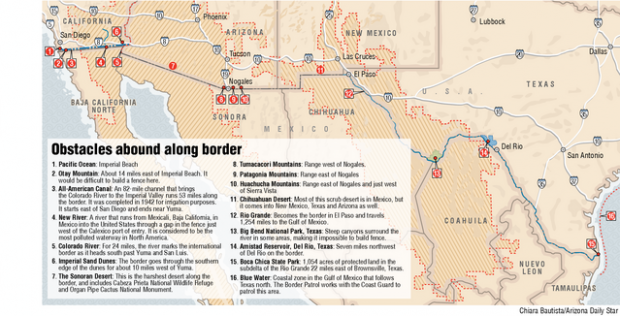

Altering the landscape is one way to secure the international line, a boundary that crosses miles of rugged canyons and more than a dozen mountain ranges, with peaks reaching 7,800 feet.

The terrain also includes an estuary, 24 miles of the Colorado River paralleled by the Salinity Canal, 53 miles of the All-American Canal, 1,254 miles of the Rio Grande, rolling sand dunes, vast stretches of desert and canyons as deep as 1,500 feet.

Without major changes like the ones the Smuggler's Gulch plan calls for, much of the U.S.-Mexican border cannot be fenced, a Star investigation found.

Of the border's nearly 2,000 miles, 85 — 4 percent — are fenced. Another 61 miles have shorter barriers that keep cars from passing but let people and wildlife through.

The U.S. House of Representatives wants to add 700 miles of double-layered border fencing. The Senate voted in May to build 370 miles of fence and nearly 500 miles of vehicle barriers, but decided last week to consider supporting the House's larger fence plan. President Bush has pledged 6,000 more agents by 2008.

Though rough terrain hinders agents' ability to patrol, reinforcing security with walls in rugged areas actually could help smugglers by providing an infrastructure — walls require roads to patrol them. Border fencing also would cost $2 billion to $5 billion or more and worries environmentalists concerned with water, wilderness preservation and animals.

"Parts of the lower Rio Grande are pretty wild. There are mountains that are really wild. There's the cost of equipment to consider," says Douglas S. Massey, a professor of sociology and public affairs at Princeton University who has studied international migration for nearly three decades.

"If you want to throw enough money at it, yes, you could do it," he says. "But you'd need to fill in 1,000-foot canyons, grade mountains. And a wall wouldn't be any good if you didn't have someone to patrol it."

From canyons to flatlands: Despite stadium lighting, rough terrain makes Smuggler's Gulch tough to patrol. The government plans to fill the 230-foot-deep canyon with dirt procured by leveling nearly mesas. Such forbidding terrain complicates plans for a border fence.

Smuggler's Gulch

As its name suggests, Smuggler's Gulch has a reputation for illegal activity — both human and drug smuggling.

In a recent daylight visit, the dark shapes of swiftly moving bodies are visible on the other side, hovering behind brush and rocks, waiting for the right moment. A corrugated steel fence across the gulch ends as the canyon rises into a small mountain to the east — where the fence becomes so low it appears easy to hop.

Before the federal government began cracking down on illegal immigration in the San Diego Sector in 1994 as part of Operation Gatekeeper, agents apprehended about a half million people each year — 1,370 per day. Now, sector apprehensions are nearly 400 per day.

But Smuggler's Gulch remains a problem because it's so difficult to patrol, though the government doesn't have specific statistics on illegal activity in the area, about two miles east of the Pacific Ocean.

"Under harsh weather conditions, it can take 10 or more minutes to get from one side of the canyon to the other," says Richard Kite, a spokesman for the San Diego Sector. The fill-in project, he says, will reduce response time significantly.

The federal government says added security is necessary to enforce U.S. laws and to prevent terrorists from entering the country. But the plan to change the topography in Smuggler's Gulch has strong opposition.

Nearby ranch owner Carol Kimzey worries the new mound of dirt will bring flooding to her home, while California legal aid lawyer Claudia Smith says the effort will push illegal entrants into deathtraps in more treacherous terrain east of San Diego. Environmentalists say the plan will destroy valuable wildlife habitat in the Tijuana Estuary, one of Southern California's last wetlands ecosystems and a nesting ground for more than 370 migratory and native bird species.

A 2005 Department of Homeland Security report says the gulch needs to be filled to "enhance both security of the border and the safety of U.S. personnel."

In September 2005, the agency's secretary, Michael Chertoff, said he'd use his power to move along the project in the name of national security, applying a waiver that led to the dismissal of a lawsuit filed by environmental groups, including the Sierra Club and the San Diego Audubon Society, which said the plan violates federal environmental-protection laws.

Though federal officials say they have no cost estimate on the gulch project, it's part of a $35 million plan to reinforce security in the San Diego Sector.

U.S. Rep. Duncan Hunter, a Republican from San Diego County and a vocal supporter of border fencing, places the costs of erecting the 700 miles of double fence in the House bill at $3.2 million per mile, or $2.2 billion for the whole project. Other border security measures could top $5 billion.

Hunter spokesman Joe Kasper says there could be "land adjustment" projects like Smuggler's Gulch in other spots on the border, although he couldn't be more specific. The House bill says that if an area's grade exceeds 10 percent, authorities may use other means to secure it.

Sixty-one percent of the San Diego Sector is fenced, with its major break at Otay Mountain in the Otay Mountain Wilderness area.

"At the mountain range, you simply don't need a fence. It's such harsh terrain it's difficult to walk, let alone drive," says Kite, the Border Patrol spokes-man. "There's no reason to disrupt the land when the land itself is a physical barrier."

Just an obelisk: In some places, such as just outside Calexico, Calif., the border is marked with just a stone, not a fence.

Calexico, Calif.

Seven miles of the 76-mile stretch in the Border Patrol's El Centro Sector are fenced, all of them around Calexico, Calif. The sector, between the Jacumba Mountains in the west and the Imperial Valley Sand Dunes to the east, is one of the most geographically diverse along the border. It includes a canal, an irrigation ditch, a north-flowing river, mountains, desert and sand dunes. In the summer, temperatures climb above 110 degrees.

Illegal entrants often try to get across the All-American Canal on "anything that floats," El Centro Border Patrol Agent Enrique Lozano says, adding that a lot of them don't know how to swim.

East of the Calexico port of entry, the All-American Canal is reinforced by an irrigation ditch that looks deceptively easy to cross. But its moldy sides are slippery and there's no vegetation to grab onto, making it nearly impossible to get out.

Last year, nine illegal entrants drowned in the El Centro Sector. Lozano says agents rescue about five people monthly.

"Any more infrastructure would help," he says. "A fence is a deterrent."

The fence of steel bars and mesh near the Calexico Port of Entry is 12 feet tall. During the day, when the port is bustling with noise and traffic, people on the Mexican side often use blowtorches and hacksaws to cut the slats, Lozano says, pointing to old bits of slag on the ground. Some use rope or homemade ladders to get over.

The Border Patrol also uses sonar technology in the area — tunnels have been found linking homes in Mexicali, Baja California and Calexico.

A gap exists in border fencing that cuts across north-south waterways on the border, including the New River in Calexico, which runs north from Mexico. The polluted river remains a common way for people to try to enter the United States.

Farther east, the Imperial Sand Dunes stretch across 10 miles of international border in sand that drifts like snow and eventually would bury any walls or fences built there.

Seven-strand: A weathered fence along the border stands west of the border towns of Naco, Ariz., and Naco, Sonora.

Arizona and New Mexico

Fencing the 24 border miles of Colorado River in Arizona would be difficult, too, says Chris Van Wagenen, spokes-man for the Border Patrol's Yuma Sector. He says the river shifts every few years.

East of the Yuma desert, the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge has 56 miles of international border, none with security fencing or barriers. Increased illegal traffic in the refuge has prompted officials there to ask for waist-high vehicle barriers.

Refuge manager Roger Di Rosa estimates building 40 miles of vehicle barriers will take two years and cost at least $30 million. There are no roads along the refuge border, so those would have to be built, too.

"Keep in mind, no single solution stands alone," Di Rosa says. "You cannot put up a vehicle barrier or a wall and walk away. It just doesn't work. You have to have what the Border Patrol calls force multipliers — barrier technology to monitor it, or else it will be breached."

East of Cabeza Prieta is Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, where 30 miles of vehicle barriers recently went up for $18 million. Rocky areas required a helicopter and heavy equipment to put them in.

The north-flowing San Pedro River west of Naco has a barbed-wire barrier across it, which needs constant repair because rainfall blows it out and it's easy to cut, says Bill Childress, manager of the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area, with about two miles of border. But a heavier fence likely would be blown out by high-velocity water during storms, he says.

Canyons, cliffs make border fence impossible: "We've got a huge ally in our geography here. I don't see how you could physically construct something here," said ranger Mark Spier of Big Bend National Park, part of which is across from the Mexican village of Boquillas.

Rio Grande

More than than half the U.S.-Mexican border — 1,254 miles — is in Texas, and less than 1 percent of it is fenced. The state's border fence consists of nearly 11 miles in El Paso and one mile behind Laredo Community College.

"We've got a big river, deep canyons. It would be a waste of time to put up a fence," says Bill Brooks, spokesman for the Border Patrol's Marfa Sector, which covers 510 border miles in West Texas.

The sector includes Big Bend National Park, an 801,000-acre federally protected area of rough terrain — 1,500-foot-deep canyons, mountains, sheer cliffs and a formidable river. Mountains there rise 7,800 feet.

"We've got a huge ally in our geography here," says Mark Spier, a Big Bend park ranger. "There are certain places where you can't go and there are certain places you can. It's like water: It's going to find its natural course, so that's where you put your dam."

The sector's 210-mile border with Mexico doesn't need a fence because of the Rio Grande, says spokesman Hilario Leal of the Border Patrol's Del Rio Sector in Texas. He also wonders if a fence would be possible — all the border land in the sector is privately owned, he says.

Ultimately, when it comes to sealing the border, national security should trump relatively modest environmental concerns, says Steven Camarota, research director for the Center for Immigration Studies, which supports a border wall.

"Most people realize that having fences on 4 percent of the border is not going to do it. If it makes sense to spend $400 billion a year on national defense, it would make sense to spend a few billion to secure the border," he says. "Obviously, not every place would need a physical man-made barrier. There's also personnel, aerial surveillance, sensors, a whole panoply of things you would need. We're at a point where we need a fence at every point where it's practical."