BISBEE

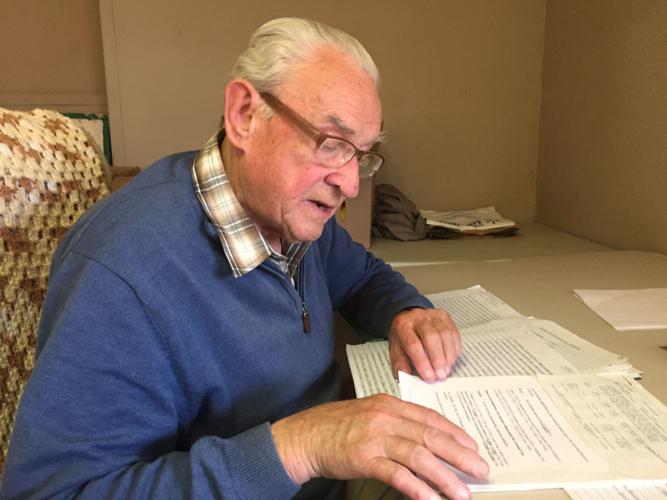

The bed Thomas Buck sleeps on is much like the ones he endured for 12 years in state prison: A thin mattress on loose springs, a bunkmate on a bed above.

Buck desperately wants to move to Texas to live, for the first time, with the woman he calls his soul mate. But instead he must make a Bisbee homeless shelter his home because, despite serving his entire term and foregoing early release, the state is keeping him under community supervision in Arizona for 17 months.

For him, overcoming that stretch feels like jumping across a canyon: Buck is 84 years old.

“If I was 30 years old, 17 months wouldn’t be too long. But for an 84-year-old man, 17 months could be a lifetime,” he said. “I’m stuck here till May 20 of 2017.”

Buck believes he was treated unfairly. He was misled, he says, by prison counselors who told him in 2014 that if he served out his entire 10-year term, rather than taking early release, he would not have to do community supervision — commonly known as parole — and could leave the state. Prisoners call that “killing your number.”

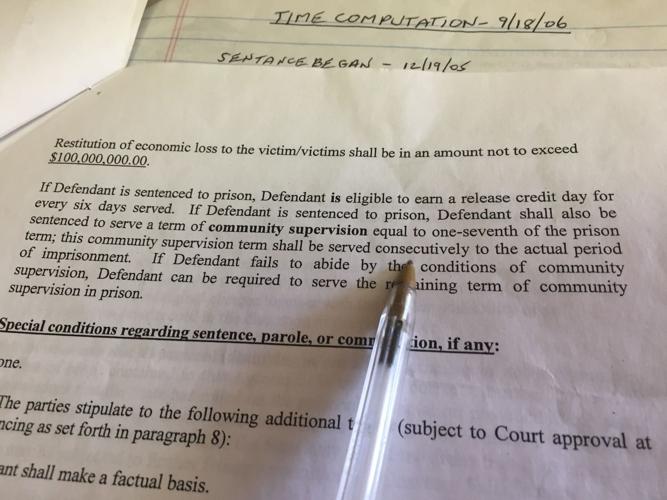

If a prison employee really gave such bad advice, that’s a problem. But my research suggests the real problem is broader than one octogenarian’s case. Not only must a non-violent criminal like Buck serve 85 percent of his term under Arizona’s excessive truth-in-sentencing laws, but he also must do court-ordered community service after the entire length of the original prison term is up, Arizona Department of Corrections spokesman Andrew Wilder told me, citing the statutes that seem to prove him right.

In other words, a person with a 10-year sentence may get out after serving 8½ years of his prison term, spend the remaining 1½ years under prison-required community supervision, and only then go on to the original term of supervision that the judge ordered, as required by state law. Statutes dictate that term as one day of supervision for every seven days of the original prison term.

For someone in Buck’s situation, that feels like a life sentence.

Buck grew up in Montreal but moved to Texas as a young man. He married an American woman, became a citizen and spent years in a variety of businesses — banking, shoes, restaurants. He was living in Texas in 1980 when he met Patty Huffman and began an affair with her.

The relationship would prove to be the root of Buck’s problems, as well as a dream come true.

“We go through life and most of us don’t have the luck to find that exact, perfect match,” he said.

Unfortunately, that exact, perfect match was not his wife, whom Buck remained married to for the rest of her life, for decades after she first found out about the affair, he said. She died while he was in prison.

In 1989, Buck and his wife moved to Dewey, Ariz., and went into business with their son Todd, running a local chain of markets. In 1994, Buck said, he transferred ownership of the store to his son and began taking Social Security. That transfer turned Buck’s unethical behavior into a crime.

The whole time the family owned the stores, Buck was secretly taking money from the stores. He was sending it to support Huffman in Texas, who was beginning to have health problems and was living on Social Security disability payments. That wasn’t illegal as long as he owned the store, but when his son was owner, it became a crime.

In 2003, Todd Buck figured it out, called the police and had his father arrested. Convicted of theft, Buck was sentenced to 2½ years in prison. But that was just an appetizer to the multi-course meal of prison life Buck was about to consume.

In 2006, Buck was indicted on similar theft charges, all stemming from the same pattern of sending store money to his mistress, just from an earlier period. Yavapai County’s justice system decided not only that it was a separate crime, but that his earlier conviction amounted to a prior offense and therefore worthy of harsher punishment. In July 2006, Buck got a 10-year sentence.

During that second sentence, Todd died. To ensure I understood a victim’s perspective, I spoke Friday with another family member, but she declined to speak for inclusion in this column and asked not to be named.

That 10-year sentence was a long time for a 74-year-old man, as Buck was on the date of his second sentencing. What’s amazing when you speak to him now, 10 hard years later, is his agility and mental sharpness. He showed me around the cramped, temporary shelter where he is living, excited about all the donations collected from area supermarkets to put in food baskets for the needy who show up for dinner at the Bisbee Coalition for the Homeless in the Tin Town neighborhood.

“You want to get a laugh?” he asked, pointing me into a narrow doorway where there was a tiny bathroom. “Go ahead and look at that toilet and tell me if you could use that toilet very well. If I ever catch the architect who designed that, I’m going to string him up.”

Buck laughed as he said this, but becomes stern when he talks about prison. He doesn’t excuse his crimes or even gripe about the long sentence he was given. In fact, he prefers not to talk about life in prison at all.

“I’ve left that in the past,” he said. What he can’t ignore is what he learned being on the inside.

“I am absolutely appalled at the criminal justice system,” he said.

The discovery that shocked him most is the fact that it is an industry, trafficking in human lives for profit. This is something that as an ordinary Arizona man, involved in business and everyday pursuits, he was never exposed to. Now it motivates him.

He didn’t know about the private prisons guaranteed enough inmates to make a profit, about the 15-minute phone calls that cost $5, about the cheap prison food and services that the state pays for dearly. He was ignorant of the fact that inmates are paid 50 cents per hour for work they do outside prison, while the prison system collects the legal minimum wage for their work.

He considers the whole thing a racket. And now he sees his precious remaining days being stolen by the same syndicate.

I called but never heard back from Buck’s public defender in Yavapai County on whether she thought he was being treated correctly. Two experienced criminal-defense attorneys I consulted in Tucson had not heard of the kind of treatment Buck was receiving and also were under the belief that if he served out his term, instead of taking early release at 85 percent of his sentence, he’d be free to go.

The chief deputy county attorney in Yavapai County, Dennis McGrane, told me that understanding was incorrect.

“To use prison parlance, there is no way to ‘kill that number’ in prison,” he said. “If you look at it from a public-safety standpoint, they want to ensure there’s a transition period between prison and total freedom.”

There is a system for transferring inmates from supervision in one state to supervision in another, but Buck doesn’t meet the requirements for mandatory transfers between states because he doesn’t have family with whom he could live in Texas. What he hasn’t taken advantage of, Wilder told me, is a system of discretionary transfers, where the inmate requests that another state take him under its supervision voluntarily.

That may solve Buck’s problem in the end, but that doesn’t solve the broader problem of criminal justice in Arizona that his case brings up. At 85 percent, the mandatory prison time for even non-violent offenders is extraordinarily long compared to almost every other state. And these little-known laws keep the state’s claws in some inmates long after they’ve shown they are making it on the outside, keeping them from getting on with their lives.

In Buck’s case, they are keeping apart a pair of star-crossed lovers who just want the chance to finally be together for a little while.

“I bet I have a thousand letters from him, and he’s got a thousand from me,” Patty Huffman told me from the home in Wylie, Texas where she wants Buck to come live.

“It seems like more than half of my life I’ve waited on him,” she said. “It just seems like a dream that will never happen.”