If A-10s stop flying from Davis-Monthan Air Force Base and no new flying mission takes their place, Tucson would say goodbye to 2,000 or more pilots, maintenance airmen and women and support staff — and roughly $187 million a year.

If the base’s fleet of 14 EC-130 electronic-warfare planes is halved next year as the Air Force proposes, that would cost our economy another $62 million.

And those estimates are probably low because the base uses a conservative annual economic-impact model, says Alberta Charney, senior research economist with the University of Arizona’s Eller College of Management.

Deep cuts at D-M would deal the economy a serious blow at a vulnerable time, and potentially curtail growth for years to come, economists say.

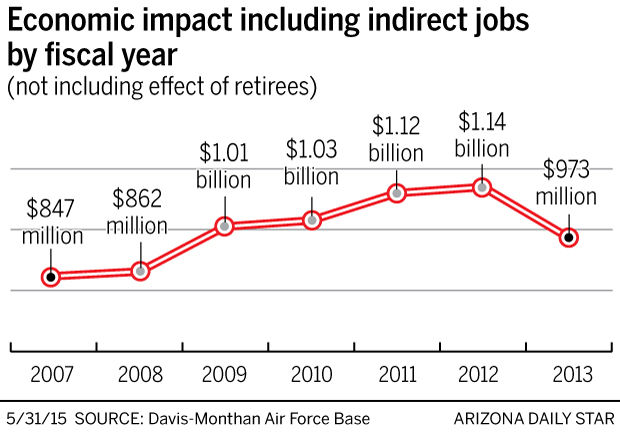

D-M employs about 9,000 military and civilian personnel. It pumps nearly $1 billion annually into the economy, with another $500 million coming from an estimated 19,000 military retirees who live near the base.

The economy wouldn’t collapse without D-M. The base's estimated economic impact represented about 3 percent of Tucson’s $35 billion annual gross domestic product in 2013.

But its closure would ripple across the economy, biting into the bottom lines of businesses, potentially lowering home values and increasing unemployment.

“It’s not just military and defense, but there is an ultimate impact on other related industries, as well as on businesses like auto dealers,” says David Godlewski, chairman of the Southern Arizona Defense Alliance.

LOCAL IMPACT

D-M supports some local businesses directly. For example, it spent $232 million in 2013 on construction, services and materials, equipment and supplies, much of it sourced locally.

Subcontractor Jason Wissinger with Babby-Henkel Building Specialties places ceiling tiles inside the Aircraft Maintenance and Regeneration Group’s hangar at Davis-Monthan.

Some of the base’s economic impact is less direct but just as significant.

At certain apartment complexes near D-M, military tenants make up 20 percent of total renters, says Omar Mireles, executive vice president of HSL Properties, one of Tucson’s biggest apartment owners. About 75 percent of D-M’s roughly 7,500 military personnel live off base, and many of them rent.

Deep cuts at D-M would likely have a commensurate effect on rental rates and even home values, Mireles says: “The impact of D-M to the economy cannot be overstated.”

HSL manages 8,400 rental units in the Tucson area and employs more than 800 people. Mireles’ boss, Humberto Lopez, is a member of the DM50, whose goal is to support and protect the base.

Thoroughbred Nissan in Tucson, 2009.

Similarly, Thoroughbred Nissan, on East 22nd Street about a mile from D-M’s main gates, has operated for about 45 years, selling Datsuns to D-M airmen during the Vietnam War.

General manager Johnny Lohrman says airmen make up a significant chunk of sales and service, noting that Nissan offers discounts to military members.

“We do a lot of business with airmen from D-M and (soldiers from) Fort Huachuca,” he says.

On any given day, you’re also likely to see D-M airmen in their camouflage uniforms eating at local restaurants such as El Sur, which has two locations near base gates.

Isela Mejia, who owns the restaurants with her husband, Omar, says customers from the base comprise up to 30 percent of their clientele.

“It’s really important to our business,” she says. Closure or deep cuts at D-M “would definitely impact not only our business but lots of other local businesses.”

MILITARY RETIREES

D-M’s presence has fostered a large military retiree community that represents an important economic bloc. The roughly 19,000 former D-M airmen and others who live in Tucson draw some $500 million in retirement pay annually.

The retirees — many of whom became familiar with Tucson while being stationed here — are able to take advantage of base amenities and services, including shopping and restaurants, health care, a golf course and various personal services. Military retirees have access to base facilities no matter the branch of the armed forces they served.

If not for the base, many would leave: An Air Force report during a round of base closures in the early 1990s estimated that up to 10 percent of local military retirees would move if D-M closed.