For some children, their classroom might be in their neighborhood public school. For others, it might be on a private or charter school campus — or even in front of a computer screen or on a museum visit with a parent.

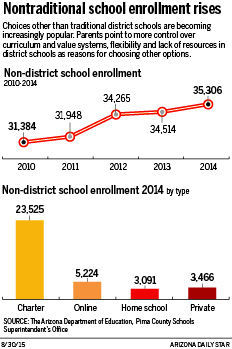

Two of every 10 students in Pima County are enrolled in nontraditional schools, a category that includes charter, private, online and home schools. The number of students choosing nontraditional options is growing each year — and some education experts say that could be to the detriment of traditional district schools.

Sharon Schisel used to send her kids to district schools but says she witnessed inappropriate behavior there, including bullying, and the values she taught at home were “constantly being undone” at school.

She enrolled her oldest son in an online school after he finished fifth grade. The family enjoyed the additional time together and her son was doing well academically, so she moved her other children to online schools as well.

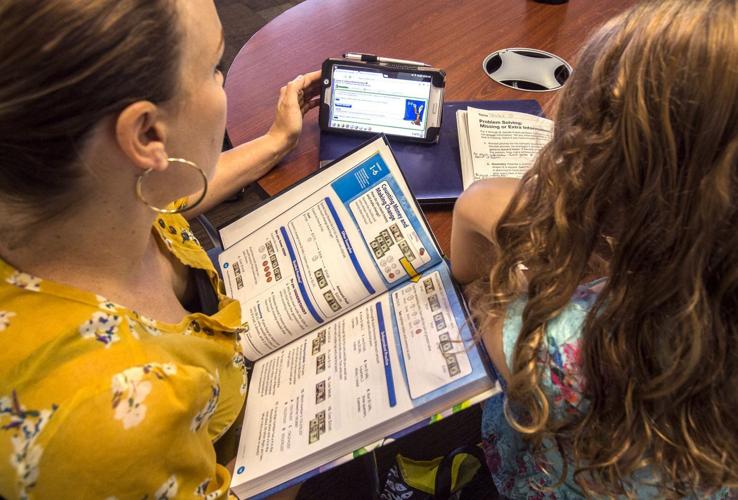

One recent Monday morning, Skarlet Schisel, a fourth-grader and the third child of the Schisel family, works in the study room of an east-side library. She flips through the pages of a math textbook while her mother scrolls a Web page on her tablet, checking on her daughter’s progress.

Skarlet attends Arizona Connections Academy, which provides her with a desktop computer, textbooks, workbooks and a certified teacher who oversees her learning.

“I love the flexibility,” Sharon said. “There’s a lot of freedom.”

Parents like Schisel who chose nontraditional education options cite the lack of resources and conflicting values taught at district schools, a desire to have more control over learning content and flexibility as reasons for switching.

Their numbers are growing: At least 35,000 of the roughly 160,000 school-age children in Pima County were enrolled in charter, online and private schools or were home-schooled in 2014, compared to about 31,000 in 2010, data from the Arizona Department of Education and the Pima County Schools Superintendent’s Office show.

The number could actually be far greater: It doesn’t include students enrolled in district-sponsored charter or online schools or those attending online schools registered outside of Pima County.

Not surprisingly, as nontraditional enrollment grows, public school enrollment declines. District schools in Pima County lost about 5,000 students between 2010 and 2014 while the area’s population of school-age kids stayed roughly the same.

The increasing popularity of nontraditional options is forcing districts to adapt, said Ricardo Hernandez, chief financial officer at the Pima County Schools Superintendent’s Office. Sometimes that means downsizing or closing schools.

“You’re going to see the morphing of school districts,” he said. “They’re going to have to take a look at why are people so entranced.”

Not “just another kid”

“Choice” was a recurring theme in parents’ reasons for choosing a non-district school, whether it was choice based on flexibility in schedule, control over curriculum or dissatisfaction with district schools.

Tamara Boudou, who home-schools her 9-year-old son, said policies at district schools drove her away — particularly their heavy emphasis on Common Core and standardized testing.

“I think that the kids can learn a lot more in a different environment,” Boudou said.

After looking at all possible options, she concluded that she wanted all of her child’s learning to be more intentional.

Both Schisel, the online school parent, and Boudou supplement their children’s learning by organizing group activities and field trips with friends in similar situations.

Boudou is part of a group called the Northwest Tucson Homeschoolers, which shares resources and organizes group classes, including PE and arts.

Amy Ferber, whose two daughters attend Sonoran Science Academy, a charter school, said the district school her daughter attended for first grade did not seem to support the child’s aptitude. There, first-graders and kindergarteners were combined in one classroom.

“It just wasn’t enough for me,” she said. “My daughter had done so well in kindergarten and then it was just a huge step back for us educationally.”

Another concern for Ferber was the size of the school and the classes. She felt her child was not getting the attention she needed at her former district school.

At Sonoran Science Academy, “My kids don’t feel like just another kid,” she said.

Gaining POPULARITY

The popularity of online and charter schools has been surging since the late 1990s.

Only eight states in the United States offered full-time online learning in 2002, said Susan Patrick, president and CEO of the International Association for K-12 Online Learning. Today there are 31, including Arizona.

Traditional schools have caught on to online learning as well, Patrick said. Pima County districts that offer some type of online option include Ajo, Amphitheater, Flowing Wells, Marana, Sunnyside, Tucson Unified and Vail.

“The big idea is that today, in the 21st century, we can use technology to support these new learning models that empower our teachers and meet students’ needs,” Patrick said.

Charter schools have multiplied by the dozens in Arizona since a state law authorizing them was passed in 1994, said Eileen Sigmund, president and CEO of the Arizona Charter Schools Association. In the 2015-2016 school year, 22 new charter schools opened in the state.

“Families and students are looking for choice and finding it in charters,” she said. Even among charters, there is a range of options, including Montessori schools and STEM — science, technology, engineering and mathematics — schools.

Trend could plateau

Growth in online and charter enrollment may plateau in the coming years.

Patrick, of the online learning association, said she predicts full-time online school enrollment will cap at 10 percent of the population of school-age children.

“The reasons are socioeconomic,” she said. “Many families have both parents working. The custodial role that brick-and-mortar schools play is really important for those families that don’t have anybody at home.”

Only so many people can afford to have a parent oversee the learning process for full-time online students, she added.

For charters, a federal grant that provided start-up assistance has gone away, which should slow the opening of new schools, said Sigmund, of the charter schools association.

Hernandez, of the Pima County Schools Superintendent’s Office, said he expects enrollment at non-district schools will continue to grow as parents learn more about their choices. But at some point, he said, it will level off.

A statewide teacher shortage affects all types of schools, he said. And in the future, charters looking to open new locations will run into space issues.

Public DISTRICTS ADAPT

District schools are scrambling to retain students as more seek other options.

When Legacy Traditional School, a charter, opened in Marana, the Marana Unified School District lost some 400 students, said Doug Wilson, the district’s superintendent. Some ended up coming back to the district.

Each student accounts for about $5,000 in funding, he said. If the district were to lose 100 students, that means about $500,000 lost.

In order not to expand class sizes or cut other vital functions of schools, the district had to get creative, he said.

“We have become a really efficient school district,” he said, pointing to how the district saved about $500,000 in utility bills.

And last year, when Leman Academy of Excellence, another charter school, announced its opening, the district responded with a marketing campaign that highlighted what the district’s schools could offer versus charter schools. Marana Unified lost about 150 students to Leman, he said.

“I respect the fact that the parents have a choice,” he said. “The only thing we can control is the quality of education we can provide.”

Charter and district schools, both of which are state-funded public schools, draw from the same funding pot, even though charters enjoy more autonomy in instructional methods, and funding mechanisms are different for each type.

Neighborhood schools are often the heart of their communities, said Ann-Eve Pedersen, president of the Arizona Education Network, which advocates for public school education.

“We all live together,” she said. “We work together. We need our children — who are going to be our future leaders — to understand other groups of people and not just understand themselves.”