Pluto has been added to the University of Arizona’s scale-model walking tour of the solar system, but will that be enough to mend the dwarf planet’s broken heart?

Not likely, according to a recent study by researchers at the U of A and elsewhere on the origins of Pluto’s distinctive heart-shaped impact scar.

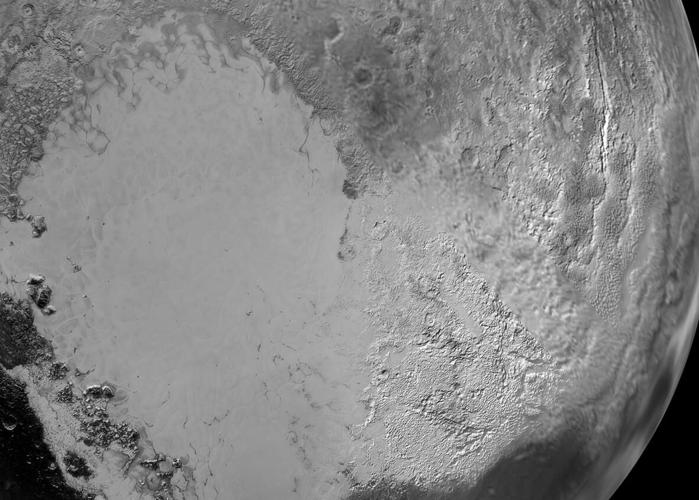

The so-called “heart of Pluto” was first discovered in 2015, when NASA’s New Horizons space probe beamed back the first close-up images of the distant, demoted dwarf planet.

Scientists have been trying to make sense of the surface feature’s unusual shape, composition and elevation ever since.

The heart — or at least the western half of it — has probably been there for billions of years, according to planetary scientist Adeene Denton, a postdoctoral researcher at the U of A’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory.

NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft captured this high-resolution enhanced color view of Pluto on July 14, 2015. The dwarf planet’s surface is dominated by a light, heart-shaped feature known as Tombaugh Regio in honor of astronomer Clyde Tombaugh, who discovered Pluto in 1930 while working at Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff.

Denton is one of the co-authors of a research paper that explores the possible origin of Pluto’s most prominent surface feature.

The entire heart is known as the Tombaugh Regio in honor of astronomer Clyde Tombaugh, who discovered Pluto in 1930 while working at Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff. The new paper focuses on the Sputnik Planitia, a teardrop-shaped basin that forms the heart’s left lobe.

Researchers from the U of A and the University of Bern in Switzerland used mathematical simulations to determine what sort of impact might have formed such a basin, which is roughly 1,240 miles long, 745 miles wide and more than two miles deep.

University of Arizona post-doctoral researcher and project lead Zarah Brown poses next to the newly installed Pluto sign along University Boulevard, just east of Euclid Avenue. The final entry in the U of A’s scale-model walking tour of the solar system was installed on May 23.

The most likely culprit was a ball of ice and rock larger than the state of Arizona that plowed into Pluto at a roughly 30-degree angle and a relatively low velocity.

A close-up image taken by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft shows a heart-shaped feature on the surface of Pluto that is the subject of a new study by researchers at the University of Arizona and elsewhere.

Denton said the collision most likely occurred early in the solar system’s history, “when things were a bit more chaotic.”

“The impact is, presumably, ancient,” she said. “But we can’t say for sure.”

The research team’s simulations also suggest that Pluto might not have a subsurface ocean as previously thought.

Their findings were published April 15 in the journal Nature Astronomy, with Bern research associate Harry Ballantyne as lead author and U of A professor Erik Asphaug and Bern’s Alexandre Emsenhuber and Martin Jutzi as co-authors, along with Denton.

Though Pluto was stripped of its planetary status by the International Astronomical Union in 2006, it was always part of the plans for the Arizona Scale Model Solar System.

The sprawling installation on the U of A campus was dreamed up by Zarah Brown, now a postdoctoral researcher, as a way to illustrate the vastness of the solar system while highlighting some of the university’s many contributions to planetary science.

The first 10 plaques representing the sun, the eight official planets and the asteroid belt were installed in August at distances carefully measured out across more than half a mile to reflect their relative positions in orbit.

But Pluto’s stupefying distance from the sun complicated things. To fit it in, even at 1:5 billion scale, Brown had to extend the model solar system another 670 feet into the commercial district beyond the western edge of campus.

Luckily, she said, the property in question, along University Boulevard just east of Euclid Avenue, is owned by the Marshall Foundation, which has a long history of supporting charitable causes and projects by U of A students.

“They agreed to host Pluto right away,” Brown said, but the actual installation was delayed by all the legal paperwork required for a property agreement between the foundation and the university.

A new Pluto plaque at the Main Gate Square shopping center on University Avenue rounds out the University of Arizona's scale model of the solar system. Even at 1:5 billion scale, the sun and Pluto are separated by almost three-quarters of a mile.

Meanwhile, Brown had a few detours of her own to navigate, including defending her Ph.D. dissertation on Saturn in November, graduating in December and welcoming her very own dwarf planet (otherwise known as a baby) in January.

As a result of all that, it took until May 23 for Pluto to finally take its rightful place at the outer limits of the model solar system — planet or not.

“The data that has come back from New Horizons just makes me love Pluto even more,” Brown said. “Science is thrilling because of the discoveries we can’t anticipate.

“Before New Horizons, Pluto was just a cluster of pixels. Now we have detailed images, and who in a million years would have guessed we would find this heart-shaped feature on its surface?”