The discovery of a breeding, northern Sonora ocelot population just south of the border is a good sign for binational wildlife conservation — and a reminder of the planned border wall’s potential to block wildlife migration, say researchers who worked on a new study of the ocelots.

This northernmost known breeding population of endangered ocelot was detected on a conservation-oriented ranch lying amidst mountainous terrain, some 30 miles south of the border, says the new study. It was published Monday in PeerJ, a scientific journal.

Using remote cameras, researchers got photos of 18 ocelots over an eight-year period. They included eight males, five females and five of undetermined gender.

The endangered ocelots were photographed in separate research efforts, from 2007 through 2011 and from 2015 through 2018. A female with a kitten, of unknown sex and probably younger than 2, were photographed in February 2011, documenting the breeding activity, the study said.

Their presence makes this area a likely source of the five ocelots who have been photographed in southern Arizona mountains over the past decade, the study said. Understanding these cats’ behavior will improve ocelot conservation on both sides of the border, the study said.

“I think it’s important that we see them all as one population instead of trying to see them as Arizona and Sonoran populations. They’re all the same, all in the Sky Islands,” said Sergio Avila, a Tucson biologist who worked on the new study. “I would not divide them.”

Having a breeding population of endangered ocelots this far north is “pretty exciting,” added Jim Rorabaugh, a retired U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist and the study’s lead researcher.

“That’s not to say this breeding population doesn’t go farther north,” since the oak woodland terrain and other vegetation at the cattle ranch continues north through the Sierra Los Pintos range southeast of Nogales, Rorabaugh said. Similar vegetation extends across the Santa Cruz River to the Sierra San Antonio, lying near the U.S. border at the southern end of the Patagonia Mountains in Arizona, he said.

Border wall a threat

But the border wall also threatens the study’s ocelot and other mammal crossings into the U.S., the researchers say. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security has planned a 26-mile section of wall almost directly north of the ranch, which lies southeast of Nogales.

But it hasn’t yet obtained the money needed to build it. It’s now building three other stretches of wall in Arizona: south of Yuma, in the Lukeville area (about 150 miles southwest of Tucson) and near the Douglas-Agua Prieta area.

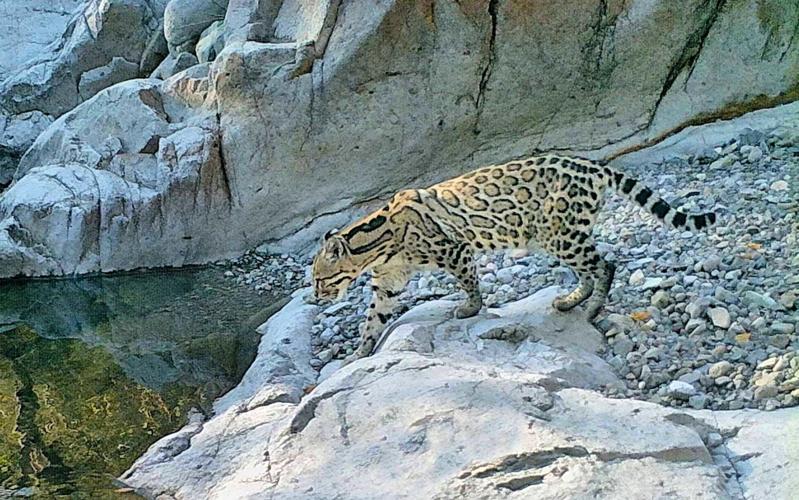

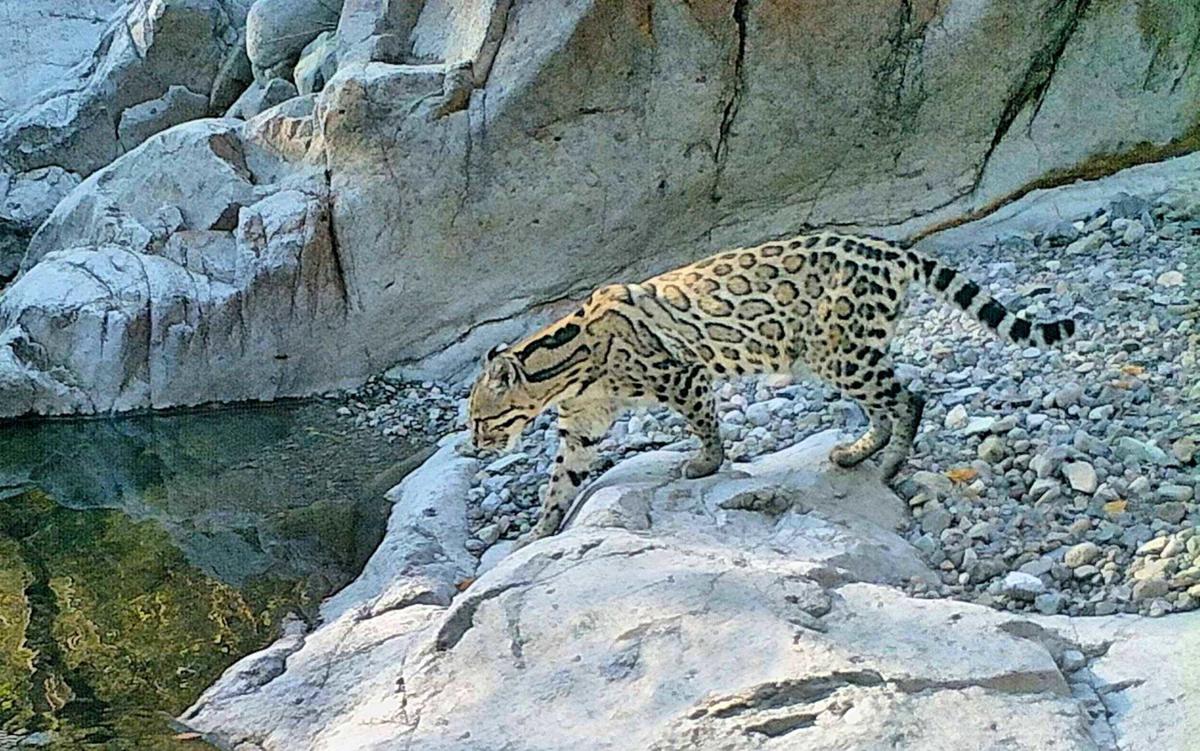

A new ocelot study identified 18 ocelots, mostly males, at Rancho El Aribabi, a conservation ranch located in Sonora, Mexico, just south of the U.S. border.

The latter stretch of construction is happening near where a still-unpublished study photographed male and female ocelots over the past five years. That study found about the same number of ocelots as the other study did, said Jan Schipper, who worked on both studies as director of the Phoenix Zoo’s field conservation research.

While both males and females were photographed, that study’s researchers found no evidence they were reproducing,

“You assume it because there were males and females but you can’t prove it,” said Schipper.

As for the wall, Rorabaugh asked, “Could they physically pass through a wall with bollards (posts) that are 4 inches apart? Maybe an ocelot could squeeze through; but would they?”

Wall construction will bring disturbances such as vehicles, paved road and other signs of human presence, “and one thing that was pretty clear from our study is that ocelots are pretty sensitive to various kinds of human disturbance,” Rorabaugh said.

“They also don’t like open areas, and where they clear around the wall, that would be a deterrent as well. They are pretty nocturnal, and if there are lights along the wall that’s probably not going to be very good for an ocelot either.”

Border walls threaten all wildlife species in this region, added Avila. He helped run the first four years of camera trapping as Mexican program coordinator for the Tucson-based Sky Island Alliance.

“And it’s not only the wall. It’s the destruction of habitat, impacts on public lands, opening roads and checkpoints, construction materials and construction trucks,” said Avila, now local outdoors program coordinator for the Sierra Club’s Southwest region.

Ranch a wildlife magnet

The ocelots in the new study were found at Rancho El Aribabi, a 30,000-acre ranch that has been a magnet for birdwatchers and other wildlife lovers for at least a decade. The area studied is where Carlos Robles Elias, heir to a longtime ranching family, manages about one-third of the ranch for conservation.

He fences off riverfront riparian areas from cattle and rotates cows in and out of pastures to allow resting, Rorabaugh said. During the first round of ocelot camera trapping, Elias limited cattle numbers to 150 or fewer at times and briefly had the ranch cattle-free until economic pressures prompted him to resume grazing.

In 2011, the Mexican government designated sections of Aribabi where ocelots have been found as a Protected Natural Area. That’s the highest level of environmental protection possible on private lands in that country. Two jaguars have also been photographed there. Conservationists call Aribabi a “core reserve” for northern Mexico.

The study’s cameras mostly photographed ocelots in and around riparian areas. The cats favored a cottonwood-laden, perennial stretch of the Rio Cocospera that resembles the San Pedro River in Southern Arizona, and a major arroyo in the Sierra Azul mountains.

Generally, the ocelots were sensitive to human activity, avoiding a major paved road on the ranch, any sign of human habitation and areas of heavy cattle use, Rorabaugh said.

From April into early July, before the monsoon rains start, cattle tend to “just park” at water sources, hanging there for hours at a time, Rorabaugh said.

“They are fouling it, drinking it down — we didn’t have any ocelots coming into places like that,” Rorabaugh said.

In an email, Elias praised Rorabaugh’s work on the study as “extraordinary.” Saying that governments aren’t doing enough to protect important species such as ocelots, he added, “Fortunately we already have a serious organization that is collaborating strongly to help us protect the place. Together, micro and tiny cells of this world, we do better things than governments.”

Conservation commitment

This discovery adds to a long list of ocelot population findings that has brought the number of records of Sonora ocelots to 174, said Tom Van Devender, a Tucson biologist who is heading up yet another ocelot study. His research has documented ocelot records dating back to the 1930s and found that ocelots are widespread across eastern Sonora.

A new ocelot study identified 18 male and female ocelots at Rancho El Aribabi, a conservation ranch located in Sonora, Mexico, just south of the U.S. border.

“It’s a tropical animal, it’s coming from the south, and goes down as far south as South America,” he said. “It’s much more common in tropical vegetation farther south. The ones Jim Rorabaugh has are moving up north.”

Also, the ocelot discovery at Aribabi shows that many private landowners in Mexico are committed to conservation, when Mexico has no public land, Avila added.

He cited the Tucson-based conservation group Northern Jaguar Project’s success at working with neighboring Sonoran ranchers, far south of Aribabi, to protect jaguars. He cited the recovery of streams and washes at the privately owned Cuenca Los Ojos ranch south of Agua Prieta where ocelots were discovered in the still unpublished study.

He also cited the Los Fresnos conservation area, at the San Pedro’s headwaters, that’s owned by the Mexican conservation group Naturalia.

“This study in the borderlands has nothing to do with the stories we’re told about Mexico, nothing to do with violence, with danger, with bad people,” said Avila. “These landowners are people who are thinking beyond themselves and their own profits.”

A female ocelot called Coontail shown on Sept. 18, 2017 in Arroyo Tinaja, which is a tributary drainage off the Rio Cocospera in Sonora, Mexico, just south of the U.S. border. Video courtesy Jim Rorabaugh

17 photos of wildlife babies in Southern Arizona

33 photos of wildlife babies in Southern Arizona

Backyard bobcats

Updated

David Burford snapped some photos of a mama bobcat and her three kittens in the backyard of his Oro Valley home.

Backyard bobcats

Updated

David Burford snapped some photos of a mama bobcat and her three kittens in the backyard of his Oro Valley home.

Southern Arizona Wildlife Babies

Updated

Steve and Sandy Sutherland caught this fawn outside their far east-side home. Mark Hart, spokesman for the Arizona Game and Fish Department, says the animal could be a mule deer.

Southern Arizona Wildlife Babies

Updated

Bobcat kitten on the wall

Mom with her 3 owlets

Updated

Great horned owl in midtown with her 3 baby owlets

Quail Chicks

Updated

One week old quail chicks run with their mother at amazing speed even in 100+ Tucson temperatures.

Southern Arizona Wildlife Babies

Updated

Bobcat kittens in a tree

Southern Arizona Wildlife Babies

Updated

Linda Wallace-Gray took this photo this spring at her home in the Tucson Mountains. "This female javelina had twins although only one is in this picture. If you look closely this baby was just born as it still has its cord. ÊShe is a very attentive and caring mother. ÊThe herd comes by regularly and are very fun to watch." Submitted by Linda Wallace-Gray.

Southern Arizona Wildlife Babies

Updated

Mom and Baby Mourning Dove

Southern Arizona Wildlife Babies

Updated

Bobcat kitten in a tree

Mama and baby

Updated

A female Bobcat and her cub rested in the shade of a shrub for an hour or so, in a patio yard in Green Valley, AZ

Southern Arizona Wildlife Babies

Updated

Carrie Robin took this photo Tuesday, April 24, 2018.

Southern Arizona Wildlife Babies

Updated

This is one of 14 quail that I rescued after opening my front door and seeing a bobcat, on our front patio, eating the mother who sat on her eggs for weeks...that night I came home and 9 were hatched. I fed them then took them and the remaining eggs to the wildlife sanctuary...with one hatching in the car on the way!!! Just thought it was cute!!! and this baby is not even 24 hours old!!!! look how big already!!!

Southern Arizona snakes

Updated

A tiny baby snake the size of a quarter

Southern Arizona Wildlife Babies

Updated

Bobcat kitten on the ground

Southern Arizona Wildlife Babies

Updated

Came home from a short trip to find this mama raising her family in our courtyard right outside front door! She had triplets but one of the babies got stuck in our gate and died. She was fiercely protective of her remaining two and put them in the tree every morning as she hunted. They spent the heat of the day sleeping and playing in the cool, right at our front door!

Southern Arizona Wildlife Babies

Updated

Bobcat kitten napping on our porch

Southern Arizona Wildlife Babies

Updated

Baby Javelina with mom

Southern Arizona Wildlife Babies

Updated

Baby bunny taking refuge behind flower pot.

Wildlife, babies, Mexico

Updated

Ocelot pair near Divisaderos, Sonora

Wildlife, babies, Mexico

Updated

Ocelot pair near Divisaderos, Sonora

Wildlife, babies, Mexico

Updated

Puma kitten near Nácori Chico, Sonora

Wildlife, babies, Mexico

Updated

A pair of pumas near Divisaderos, Sonora

Wildlife, babies, Mexico

Updated

A pair of pumas near Divisaderos, Sonora

Wildlife, babies, Mexico

Updated

A Panthera near Granados, Sonora

Wildlife, babies, Mexico

Updated

A Panthera near Granados, Sonora

Wildlife, babies, Mexico

Updated

White-tailed deer and fawn near Divisaderos, Sonora

Wildlife, babies, Mexico

Updated

White-tailed deer and fawn in Sonora

Wildlife, babies, Mexico

Updated

White-tailed deer and fawn in Sonora

Wildlife, babies, Mexico

Updated

White-tailed deer in Sonora

Wildlife, babies, Mexico

Updated

White-tailed deer near Divisaderos, Sonora

Wildlife, babies, Mexico

Updated

White-tailed deer near Divisaderos, Sonora

Wildlife, babies, Mexico

Updated

Coatis near Divisaderos, Sonora