“Not to know a rule in art and break it is bad art, but to know a rule and break it is good art. Only by knowing the rules and breaking them will one develop an individual style.”

— Ettore (Ted) DeGrazia

Did you ever wonder why anyone decides to write a biography of a particular person? What piques a writer’s curiosity enough to spend months or even years meticulously researching every detail of that person’s life?

I got at least one answer a few weeks ago while attending a Friday evening book review featuring authors James and Marilyn Johnson speaking on their recently published “DeGrazia: The Man and the Myths” (The University of Arizona Press, February 2014).

It seems that while browsing around the DeGrazia Gallery in the Sun's gift shop, 6300 N. Swan Road, in 2010, the Johnsons asked to see a biography of the artist. Turns out such a biography did not exist.

As Marilyn Johnson explained, “At that moment, a light bulb went off in my husband’s head.“

James Johnson was a professor emeritus of journalism at the University of Arizona. Marilyn Johnson had worked as a journalist. Here was fertile, untapped ground for the couple’s interest in researching and recounting people’s lives.

And recount they did that Friday night. I learned that this many-faceted, multitalented artist was so much more than a painter of angels and faceless children.

While doing a bit more research on my own, I began to see DeGrazia as an artistic maverick, with little regard for most people’s opinions.

The Tucson icon was born in 1909 to an Italian family in the mining town of Morenci, when Arizona was still a territory. Just as Arizona later came into its own as our 48th state, DeGrazia gradually developed as an artist.

When the Phelps Dodge mine closed in 1920, the elder DeGrazia moved his family back to Italy. After the mine reopened in 1925, the family returned to Morenci. By this time, son Ettore had forgotten how to speak English and had to go back to first grade as a 16-year-old.

One can only imagine the determination it took for the teenager to study in the same room with a class of 6-year-olds. That determination was to mark the rest of DeGrazia’s life.

One of his teachers had trouble pronouncing the name "Ettore," and started calling him Ted. The sobriquet stuck.

After graduating from high school at age 23, he worked for a time in the mines, but was never happy there — like many artists, DeGrazia needed sunlight.

In 1933, he hitched a ride to Tucson — with his trumpet and $15 — and enrolled at the UA, where he would earn two bachelor’s degrees and a master’s degree.

Marrying Alexandra Diamos in 1936, he later moved to Bisbee with her to manage one of his father-in-law’s movie theaters. A frustrated artist, DeGrazia set up his own studio, and spent every spare minute painting.

Back in Tucson in 1944, DeGrazia could not find enough buyers for his work, which was often on the serious side, with political overtones — like images of the Mexican Revolution and poor peasants.

So he decided to open his own gallery on the corner of East Prince Road and North Campbell Avenue. The landmark has since been torn down, and is now a gas station.

He often did not have enough money for canvas, and improvised on any material.

One day a man came into Rosita's Café next to the gallery and verbally attacked DeGrazia.

“You’re the guy who thinks you can paint on whatever you want, right? No rules, you just do whatever you want.”

The artist began painting a tortilla that was on the table (the tortilla is today on display in the Gallery of the Sun), and also autographed the man’s white shirt. “Now I have painted on everything,” he said.

DeGrazia started to get some coverage from Arizona Highways magazine, but he was still not popular with the masses, nor was he making a lot of money. People seemed drawn to his pictures of angels and children.

He kept the originals, but arranged for a separate company to put his iconic images, which many critics viewed as kitsch, on all manner of easily affordable objects, from coasters to refrigerator magnets.

This was in keeping with his desire to be an artist of the people, not just the wealthy.

Ironically, that decision made DeGrazia a multimillionaire who has been described as “the world’s most reproduced artist.”

According to James Johnson, becoming wealthy gave DeGrazia the chance to write and illustrate at least 15 books on Southwest history and culture, primarily of Native Americans, as well as concentrate on more serious artistic endeavors.

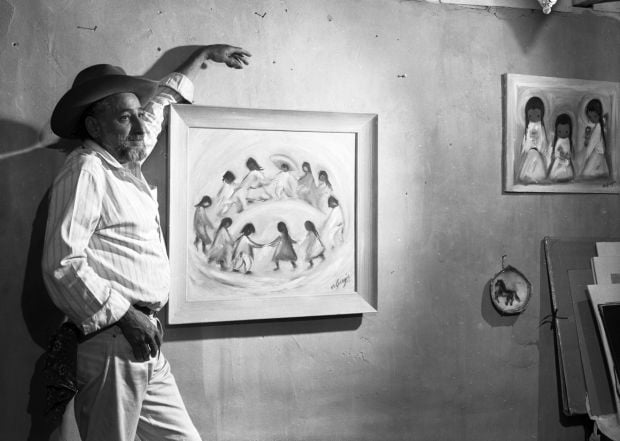

Always dressed in jeans, with a red handkerchief hanging out, flannel shirt, worn boots and hat, DeGrazia maintained the image of the eccentric artist. He wore this outfit even on television interviews and when accepting an award from the UA.

By 1950, DeGrazia felt central Tucson was getting too populated and bought 10 acres in the Pontatoc/Swan area. It was there that he built his mission (chapel) and later home, and little gallery, culminating with the main gallery, built in 1965. The area lacked running water, electricity and supplies. That suited him just fine.

DeGrazia struck pay dirt in 1960 when UNICEF put the image of “Los Niños” on its Christmas card collection. That year, more than 5 million boxes of cards bearing the image were sold around the world.

Perhaps the most stunning example of the artist’s sense of justice occurred in 1976.

Believing that the inheritance tax on artwork was unfair, he took 100 paintings, reputed to be worth $1.5 million, up to Superstition Mountain near Phoenix and burned them all. Who but DeGrazia could have thought of such an outrageous act that would bring him even more notoriety?

DeGrazia had his human frailties. Admittedly a poor father and husband, he also had a long relationship with educator Carol Locust while married to his second wife. They had a son, Domingo DeGrazia, a well-known musician and lawyer.

The elder DeGrazia died of prostate cancer in 1982.

When asked to sum up DeGrazia the man, Johnson referred to the master, who described himself as “not saint nor devil but both.”