Born in Harmony, New York, in 1869, Anna Ploss never knew her birth mother. She was eventually sent to live with George and Julie Durkee on their New York farm. It was George’s younger brother, Eugene, who founded Durkee Spices and Durkee Famous Foods, but Anna would surpass Eugene’s business acumen by becoming one of the most prosperous women miners in the country.

The Durkees supposedly adopted Anna when she was about 6 years old, although no adoption records have been found. Yet it was around this time that Anna began using the last name of Durkee.

Anna had a keen mind for figures from an early age. When she was 16, she bought just over an acre of land from her father’s second wife, then leased the land back to the woman for $1 a year.

At age 18, she started teaching, but by 1897, she was in Minneapolis working in a dry goods store. She also worked as a stenographer and at the local library. In 1900, Anna became an insurance agent for New York Life Insurance Company and went on to work for the Pennsylvania Mutual Life Insurance Company.

By 1903, she was business manager of the South Dewey Mining Company of South Dakota that ran the Dewey Tunnel site at the Thunder Mountain gold mine in the Black Hills.

When she was approached to sell copper stock for the Portage Mountain Mining Company, Anna negotiated a deal allowing her to receive 33.3% commission on each of her sales. Unfortunately, she neglected to obtain a signed contract from the company president, which would come to haunt her in later years.

In 1906, she was sent to Alaska to sell stock. There she met the supervisor of the not very successful Alaska Garnet Mining and Manufacturing Company that overlooked the Stikine River in Southeast Alaska.

“I looked it over,” Anna said, “liked it, went back home and interested 15 of my women friends. We pooled the required $10,000 and bought the mine, which was supposed to contain a small, blanket deposit. A survey revealed that our newly acquired property was literally a mountain of garnets.”

This was the first mining company in the world to have only women for officers. As Anna explained, if they allowed one man as an officer or director, he would immediately become “masterful” (her word) and believe it was his duty and privilege to dominate. She was also concerned that men who are honest with their fellow men are seldom the same with women.

Several years later, she proudly boasted, “It is pretty generally believed that a bunch of women can’t get along together for any length of time without a lot of friction, but I want to say most emphatically that it isn’t so. Fifteen of us have been closely associated for eight years now, and never once have we had any insurrections in a board meeting — we’ve gone through some pretty strenuous times too.”

While she was setting up the Garnet Mining Company, Anna filed charges against the Portage Mountain Mining Company for her stock commissions of $77,000. She won her case but only received $6,500.

The Alaska Garnet Mining Company, a $1 million corporation, produced enough deep, burgundy-colored garnets that Anna supposedly sent them to Minneapolis, where they were turned into jewelry.

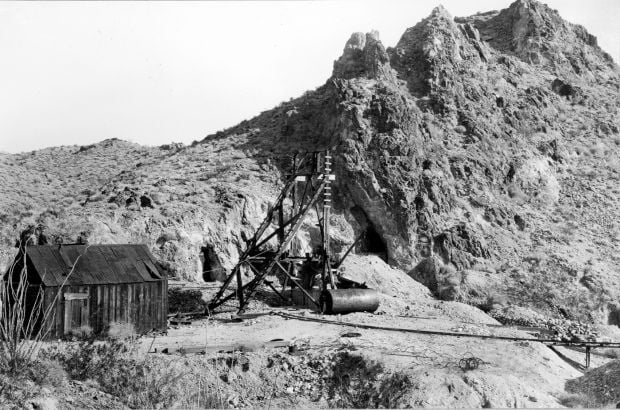

A mine in the Oatman area.

The company also sold loose garnets at the 1909 Alaska-Pacific-Yukon Exposition in Seattle and the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco. Anna shipped a large quantity of garnets to England, where they were coveted and sold briskly to jewelry makers.

Anna soon learned that the by-product from garnet waste was just as valuable, if not more so, than the gems themselves. By grinding the waste product to a certain mesh, then putting it through a special machine in what she called a secret process, the waste garnets made a separating powder or parting compound for use in foundations.

Realizing she had found a gold mine in garnet waste, Anna immediately filed for a patent on her process.

In 1915, Anna left Alaska and eventually ended up in Northern Arizona, where, for many years, the Navajo people had used what were called ant hill garnets as bullets, believing the blood red color would ensure a fatal wound.

Anna went looking for these garnets and incorporated the Dardanelles Mining Company near the Oatman/Chloride area in 1916, along with the Comstock Parallel Mining Company. She filed on at least 14 properties in the San Francisco Mining District, and by 1922, she had 20 mining properties in Arizona, including a prosperous gold and silver mine in Mohave County.

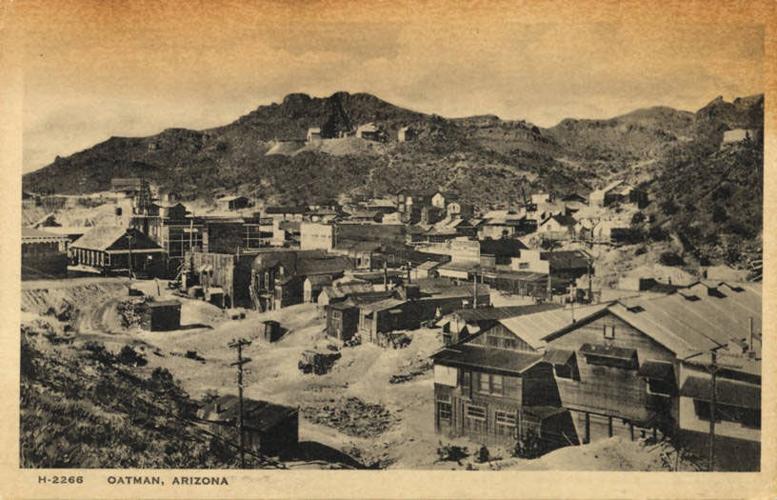

Postcard view of Oatman, Arizona and the surrounding mountains.

She was considered the largest individual mine owner in Oatman and had great hopes for the area.

“Oatman is the greatest camp in the world,” she proclaimed. “And it will come into its own in the early fall. The big capitalists are ready to make things go with a rush as soon as the weather moderates. Many of the greatest mining engineers in the world have made favorable reports on the district and it needs only the investment of capital for development purposes to open a great many mines in the Oatman district. Eastern capital is being interested and the outlook for the winter is excellent.”

All the while, she continued to control the Alaska Garnet Company. And by now, she had even added a few men to her business operations.

In a 1922 interview, Anna was asked what quality brought her the success she enjoyed. “I really do not yet consider myself a ‘success,’" she said. “I am still dreaming of things. … But I have felt that there is in me somewhat of the spirit of the pioneer, and perhaps that is one reason for the measure of progress which I have experienced.”

Anna died in 1948 at the age of 79 and is buried in Hartsdale, New York.