When Lulu Smith came to Arizona to teach in 1912, women teachers earned about $82 a month while men garnered around $118. “I came out to Phoenix to a $90-a-month teaching job,” Lulu said in a later interview, “and I thought I was sitting on top of the world.”

However, Arizona’s women teachers, who numbered 757 to 120 male teachers, were soon up in arms over the inequity in salaries. But instead of raising women’s pay, school boards lowered the men’s monthly amount, saving the districts an enormous amount of money. These were the conditions that Lulu encountered as she worked her way up the ladder of Arizona schools: from poorly paid teacher to principal to having a school named in her honor.

Lulu Smith was born in Lupus, Missouri, on Jan. 16, 1889. Within a month of her birth, her mother died, and at the age of 4, her father passed away. An aunt and uncle took her in.

The following year, Lulu and her new family headed by stagecoach to Amarillo, Texas, to run a cattle ranch. In 1902, they relocated to St. Louis, Missouri, where Lulu graduated from what is now the University of Central Missouri in Warrensburg in 1909. Her first teaching job was a few miles away in Eldon, Missouri. A year later, she relocated to Okmulgee, Oklahoma, just south of Tulsa, and taught for a few years before heading west in 1912.

In Phoenix Lulu taught at Adams School and later at Monroe School. Her courses of study included geography, spelling and composition.

By 1917, Lulu’s skills working with students attracted the attention of Flagstaff Normal School (now Northern Arizona University), and she was hired to educate aspiring teachers. But Phoenix missed their popular teacher, and in 1920 when Phoenix’s new Kenilworth Elementary School opened, she was enticed back to serve as principal. She remained principal for 15 years.

Kenilworth School is the oldest school in Maricopa County that is still in operation. Its buildings are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

During her years at Kenilworth, Lulu continued her own education. She received both her bachelor’s (1926) and master’s (1935) degrees from the University of Arizona.

She may have had an ulterior motive for spending so much time in Tucson. During her 2 years in Flagstaff, Lulu had met faculty member John F. Walker, who eventually became a professor at the University of Arizona. The couple stayed in touch, and in 1936, they married in Phoenix. It may not have been a long courtship, but it was a lasting one.

Lulu packed her bags and headed for Tucson with the assumption she would continue her teaching career. Unfortunately at that time, married women were precluded from teaching in the Tucson School District. Lulu could substitute teach but not hold a permanent position.

“Since I had both elementary and high school certificates,” she said, “I was shuttled around from school to school, teaching every grade from 1-C to senior high English.”

In 1943, Lulu acquired a position at Prince School in the Amphitheater School District, the only district in Tucson that allowed married women to teach full time. Lulu was finally back where she belonged — in front of a class of 4th grade students (her favorite grade). She remained at Prince until she retired in 1957.

A testament to her popularity was noted in 1954 when at the age of 65, Lulu was asked to stay on at Prince School even though teachers were expected to retire at that age. She was so well liked by the students, administrators offered to retain her as an active member of the faculty.

In 1963, Amphitheater built a new school on Roller Coaster Road in Northwest Tucson. While the road is known for its twists and turns, it now claimed not only a new school but a new concept in teaching. The school was named the Lulu Walker Elementary School.

Attending the dedication ceremony for the new school, Lulu felt “a tremendous mixture of humility and unworthiness” in having a school named in her honor. “After 40 years of teaching,” Lulu said, “I wouldn’t trade jobs with anybody.”

The Lulu Walker School was set up differently than other district schools at the time, although the team-teaching approach had been initiated about five years earlier.

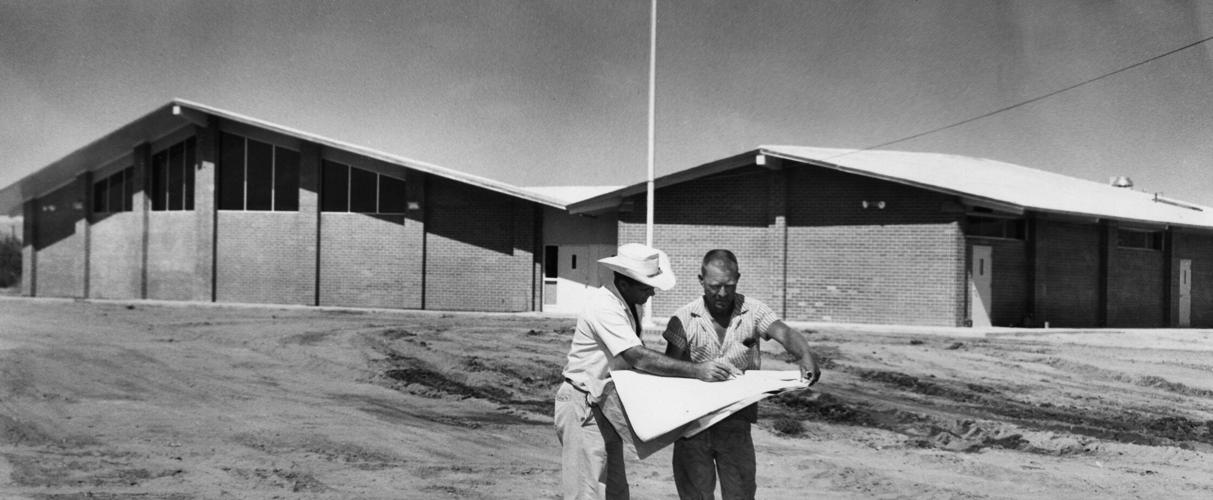

Construction officials go over the final details in October 1964 before the first phase of Walker Elementary School opens to students in the Amphitheater School District. The school was named for longtime district teacher, Lulu Walker.

Three hundred and twenty students attended classes in one of five large rooms with each of these learning centers having 3 or 4 groups working on different subjects. Each child progressed at their own pace. Teachers requested the time they needed for their classes and were not restricted to a specific time allotment.

Fascinated with this new perception on teaching. Lulu inspected the large classrooms. She had always tried to put herself in the child’s position and was concerned how young first-graders would react to male teachers, a relatively new development in schools. She was pleased to report she found no problems with either the unique teaching concept or the male teachers.

“No matter what kind of building you have or what ‘method’ you follow,” Lulu said, “your first responsibility as a teacher is always to do the very best you can for every child in your charge. This never changes.”

The Lulu Walker School team teaching method attracted educators and administrators from around the world. According to one newspaper report: “Visitors have come to look at the Walker program from seven foreign countries, 24 states outside of Arizona and 21 cities outside of Tucson. Most of them have been favorably impressed.”

After John Walker died in 1953, Lulu remained in their homestead near the university until 1970 when she moved to LaVerne, California. She died June 23, 1986, at the age of 97.

She never wavered in her desire to make a difference in the education of every child who sat in front of her and once remarked that she “wouldn’t trade jobs with anybody. If I had my life to live over, I’d still be a teacher.”