Many mountain ranges near Tucson have significantly contributed to Arizona’s mining history. These include the Sierrita, Silver Bell, Patagonia and Santa Rita Mountains, which have a similar geological origin.

They were formed by a volcanic caldera cycle involving the creation of volcanic peaks from underground magma chambers and distributed by basin and range detachment faulting.

The rugged and remote Sierrita Mountains have been mined for centuries by Spanish explorers and missionaries for silver-lead deposits and more extensively for copper in the mid-20th century at operations, including the Mission Mine Complex and the Twin Buttes open pit mine. Geologically the Sierrita Mountains consist of an intrusive granitic core surrounded by metamorphic rock.

The Senator Morgan Mine workings seen in 2012.

The Sierritas are one of the few localities in Arizona that host aquamarine found in quartz veins in granite. The mountains encompass 60 square miles measuring 12 miles north to south and up to six miles wide. Aquamarine, a gem variety of beryl, has been documented from the Palo Verde and Bella Donna claims. The location of these claims remains unknown as they have never been patented.

Other mines in and nearby the Sierrita Mountains include the Copper Glance Mine in the Twin Buttes Mining district, which had its own railroad spur for ore transport; along with the Senator Morgan Mine, worked for copper since the late 1870s.

Operated by the Twin Buttes Mining & Smelting Co., established in 1903, the Senator Morgan Mine was leased to Bush-Baxter from 1906 and 1913. It was extensively developed and stopped with a shaft depth of 900 feet and a production of 152,000 tons of copper ore valued in conjunction with silver extracted at over $2 million. Scheelite, an ore of tungsten (WO3), was later found in quartz deposits along with lime and silicified sandstone.

A small cabinet size sample of jackstraw cerussite from the Flux Mine in the Patagonia Mountains.

In 1942, Maurice d’ Autremont and David Richards leased the property from Charles M. Taylor, who discovered scheelite in disseminated quartz veins using a fluorescent lamp the prior year. They shipped more than 100 tons of ore to the Jacobs tungsten mill, northwest of the intersection of Speedway and Silverbell, 2 miles west of downtown Tucson, for testing. Low-grade values at 1.25% and faulted conditions in the geology necessitated greater mining costs, hindering ore production, and no further work was done after 1943.

The Silver Bell Mountains west of Tucson host the large Silver Bell Open Pit Mine. The formation of Silver Bell’s copper deposits dates back 75 million years. They were created by intense volcanic activity, causing the accumulation of thick layers of volcanic debris and magma chambers to form at great depths below the surface. As the magma solidified, copper-rich fluids were ejected and channeled to the surface along a fault zone spread out along a network of fractures, forming the current deposition of copper minerals.

Mining in the area is extensive and began with the discovery of high-grade oxidized copper ore at the Old Boot Mine in 1865. The arrival of the Southern Pacific Railroad 15 miles to the southwest in 1881 heightened development, with a 30-ton-per-day furnace built onsite by the Huachuca Mining and Smelting Co.

A decade later, the Silver Bell Mining Co. erected a small Tucson smelter that refined the mine site’s ore for several years.

By 1903, the Imperial Copper Co. was organized by E.B. Gage and W.F. Staunton, along with the Development Co. of America or DCA, created in 1901 to finance and oversee a network of mining and railroad operations in Arizona by magnate Frank M. Murphy.

A small cabinet size sample of azurite from the Exchange Mine nearby Helvetia in the Santa Rita Mountains.

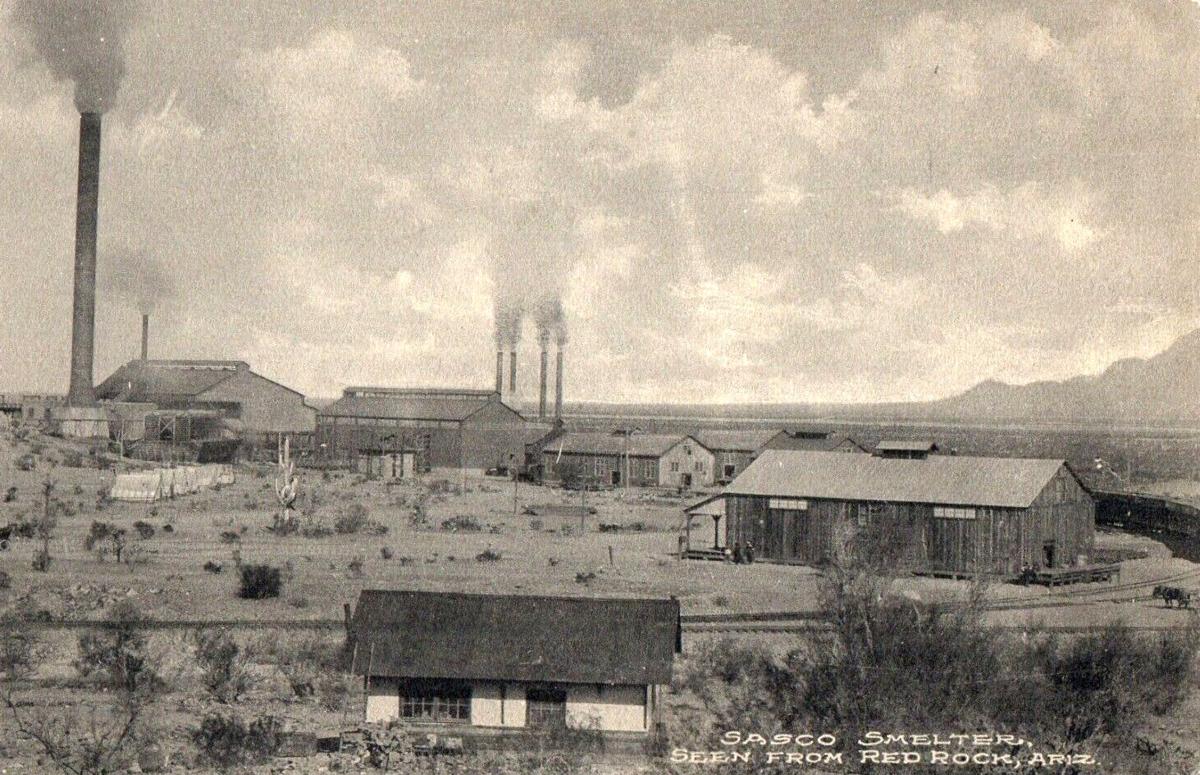

Soon established, the Silver Bell townsite reached a population of around 1,000. And by 1909, the Southern Arizona Smelter Co. (SASCO) established the company town of Sasco and a smelter west of Red Rock to process the ores of the Silver Bell Mine. The town and smelter were short-lived due to the bankruptcy of DCA involving its mining operations in Tombstone, the Spanish flu pandemic, and falling copper prices.

Dropping copper prices also forced ASARCO to suspend operations at the nearby Silverbell Mine. The mine was developed by ASARCO in 1951, including two ore bodies, El Tiro Pit and Oxide Pit, separated by two and one-half miles. Copper production continues to the present.

The Helvetia Mining district, 30 miles southeast of Tucson in the northern end of the Santa Rita Mountains, includes more than 50 mines and prospects worked sporadically since discovery in the 1870s.

By 1899, the mining camp of Helvetia was one of the largest in Pima County, with more than 300 miners on the payroll of the Helvetia Copper Co. and development occurring at the Copper World, Exchange, Heavy Weight, Isle Royal, Narragansett and Omega mines.

Thumbnail size sample of aquamarine, muscovite and quartz from the Sierrita Mountains.

Despite extensive development, including an 8,000-foot narrow gauge railroad connecting the mines in the Helvetia district to a 175-ton smelter, the mines themselves never produced significant profit, though at one time, they were on the map to receive a branch railroad from the Southern Pacific. Today, the mines are of interest among mineral collectors for the specimens they produced.

The Flux Mine in the Harshaw Mining district, four miles south of Patagonia, was a steady producer of lead and zinc from 1884 to 1963. The mine was first discovered in the 1850s and was owned and optioned with greatest production (over $3 million in period dollars) since 1940 under ASARCO.

In 1919 a 6,200-foot-long aerial rope tramway connected the mine to the 100-ton daily capacity gravity-flotation concentrating mill capable of processing lead carbonates. The operation was financed by the Flux Syndicate and lasted only several years due to high operational costs. Four thousand tons of ore and tailings were milled, producing 14 carloads of lead and silver concentrates at period markets for $16,000.

Geologically, the mine consists of rhyolite porphyry and related volcanic sedimentary deposits. The mine reached the 750-foot level, including more than 6,000 feet of tunnels, shafts, drifts, crosscuts and stopes, after which it became too low grade to profit from the metals market. The lead concentrates were shipped by rail to the El Paso smelter, and the zinc concentrates were shipped to the Amarillo smelter.

Thumbnail size sample of fluorite with galena from the Silver Bell Mine.

Fluorite drill core sample from the Silver Bell Mine.

Micromount size sample of garnet from the Silver Bell Mountains.

Small cabinet size sample of pyrite on alaskite matrix from the North Silver Bell Pit in the Silverbell Bell Mountains.

A glass mine insulator such as this one patented in 1894 by Hemingray was commonly used to prevent electric current loss of transmission in mining operations during the early 1900s including those at Silver Bell. A threaded hole through the middle allowed a malleable iron pin to drain excess water frequently encountered inside mines preventing freezing and short circuiting the attached electrical lines.

A thumbnail sample of malachite after azurite/calcite from the Omega Mine in the Santa Rita Mountains.

A thumbnail size sample of the lead and manganese mineral coronadite named after the Spanish Explorer Francisco Vasquez de Coronado from the Glove Mine located in the Tyndall Mining District on the southwestern flank of the Santa Rita Mountains.

A distant view of the Senator Morgan Mine with the Twin Buttes Mine tailings in the background circa 2012.

Get your morning recap of today's local news and read the full stories here: tucne.ws/morning