Serving as a missionary within Hopi and Navajo communities for over 50 years, Katherine Ruth Beard became the driving force behind providing housing, food, clothing and the gospel to Northern Arizona’s Native population. The Flagstaff Indian Bible Church that she helped establish still exists today.

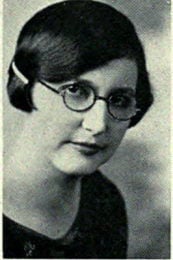

Never a strong child, Katherine once admitted, “My birth was not such a joyful occasion, for it seemed to be the climax which caused a further break in my mother’s health.” At the time she was born on May 7, 1908, in Wellington, Kansas, her mother was suffering from tuberculosis and died when Katherine was still quite young. Her father, John, died while she was in high school. She and her two older siblings (Loren and Helen) received a small inheritance that allowed Katherine to attend a teachers’ college.

After about a year, she transferred to Northwestern Bible and Missionary Training School in Minnesota. When her funds ran out, she worked in the school kitchen and took jobs in town as a maid and nanny. She graduated in 1930.

Two years later, Katherine arrived in Winslow, Arizona, with one suitcase, no place to live, very little money, and a driving ambition to minister to the Hopi and Navajo people.

She initially worked on the Hopi mesas of Pollaca and Oraibi, but Katherine was soon traipsing over unmarked trails from one hogan to another to tend to Navajo families. If she could not borrow a horse to ride out into the desert, she walked. Cars were useless on sandy trails that often disappeared without warning.

The Navajos called the petite woman with unstoppable energy “Asdzan Yazzie” or “Little Lady,” or sometimes “Little Lady with the Black Book.”

With Bible in hand, she particularly enjoyed teaching children. “How they loved the Bible stories I would tell them,” she said, “and they enjoyed the little games we played. Of course, they always were looking for that sweet gift I had, for each time I tried to carry a few bits of candy with me.”

With a donation of five acres of land to start a mission, Katherine became the driving force in establishing the Navajo Gospel Mission. She worked at the mission for 16 years. “We always had the coffee pot hot on the stove,” she said. “There is something about fellowship around a cup of coffee which is universal, and it was true among the Navajos.”

She remained respectful of their customs and beliefs, never dismissing a medicine man’s prognosis or remedy but working alongside him to elicit a cure or comfort the dying.

Donations of clothing started arriving at the mission but the Navajos refused to accept the charity unless the missionaries would take something in return. Their contributions of freshly butchered lambs and piles of firewood sustained the mission during the frigid winter months.

However, living in the basement of the small mission building, as well as walking miles to find the next hogan, Katherine’s health eventually sent her back east to recover.

Returning to Arizona, she settled in Flagstaff and ran a small storefront outstation for the Navajo Gospel Mission.

At the beginning of World War II, Native people from a variety of tribes flocked into Flagstaff, many of them to join the Army or to work at the Sixth Army Ammunition Depot that lay just outside of town. With most facilities only available to Anglos, the city asked Katherine to open a center to administer to the needs of the Native population. They offered her no salary but she accepted the challenge anyway.

“Of course, I would have gospel services and Bible studies in the center every day,” she said, “and I could deal directly with the Navajos in their own tongue (she had learned to speak Navajo from visiting the hogans). I couldn’t do that with the other tribes, but most of them (especially the Hopis) could understand English pretty well.”

Katherine started the first Indian church within the confines of the Sixth Army Ammunition Depot and throughout World War II as well as the Korean Conflict, she provided religious services to all Native people at the Depot, estimated to be a population of about 1,500. The Army eventually donated a parcel of land and erected the Little Indian Bible Church with the provision that Katherine remain in charge of the facility.

In 1948, Katherine, along with other benefactors, established the Flagstaff Mission to the Navajos, although many tribes participated in the services including Hopi, Apache, Creek, Hualapai and Havasupai. She continued to ride out into the desert to visit and pray with isolated families.

She acquired land north of Flagstaff and built a chapel closer to the reservation. Today, the Flagstaff Mission runs numerous outpost churches.

In 1956, Katherine held the first large Christmas party for the Native population. Gifts poured in from across the country and Katherine had to find room for hundreds of pounds of meat, truckloads of vegetables, tons of baby food, blankets, and clothing for all ages.

These gatherings became an annual event and attracted the attention of dozens of charities.

Age did not slow Katherine down, and she never gave up her work on the reservation. As long as she was able, she traveled across the desert seeking remote dwellings, bringing her ministry wherever it was wanted and needed. When asked how she found these often secluded homes, Katherine replied, “Just follow any track across the desert. It will lead to a hogan, or to more than one. The people are there, but you have to go out and find them.”

In 1967, supporters and friends presented Katherine with a small organ for her 35 years of service. And in 1981, North- western College named Katherine Alumnus of the Year and awarded her its Distinguished Alumni Award.

Katherine died on April 21, 1998, just days before her 90th birthday. For a child who started out weak and frail, Katherine weathered life with a gusto and fortitude with whom few would dare to compete.

How well do you know Arizona? Here is another quiz to test your knowledge on Arizona history and facts. Video by Pascal Albright / Arizona Daily Star