“You know,” said social justice activist Marjorie King, “it’s not just me. There are hundreds of people — incredible, wonderful people — religious, secular, left, right — making a beautiful effort” to help out in Tucson. “I’m just one of many.”

This 71-year-old Tucson-raised international teacher, working for migrants and the homeless, sat on her patio and tried to deflect attention from herself.

She was one of the early leaders of the Casa Mariposa Detention Visitation Program. She took part in the Casa Mariposa project, aiding migrants, out of which grew the Casa Alitas Welcome Center. She now volunteers at Casa Alitas, staffs the welcome desk for the homeless at Grace St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, coordinates the church’s Migrant Ministry, sits on the church’s governing body, and is pursuing an outreach youth program. A member of the Episcopal Diocese of Arizona Borderlands Council, King supports the Casa de Misericordia migrant shelter in Nogales, Sonora.

As the Rev. Delle McCormick, retired pastor of Rincon Congregational Church, says, “Margie is an unstoppable force.” While most folks focus on one or two areas, King has a hand in everything.

Her career set her up for these retirement pursuits. Armed with a University of Arizona bachelor’s degree in history and Spanish, King headed eastward for graduate school. At Ohio State and Temple, she embraced Asian studies and the Chinese language and ended up teaching kids from elementary school to college in the U.S., Taiwan and China. She wrote a biography of China-born activist and writer Ida Pruitt that’s being re-issued in English and Chinese.

“They say women can have it all,” she quips, “and I tried.”

In 2011, when she retired from her final position, at Shantau University in Guangdong, China, she returned home.

So, how did she get from teaching Asian American Studies in Guangdong province to aiding asylum seekers in Southern Arizona?

She got a call. “Casa Mariposa needs a Chinese speaker,” she was told. Immigration and Customs Enforcement was dropping off asylum seekers at the Greyhound bus station downtown, and no one knew what to do with folks speaking Mandarin.

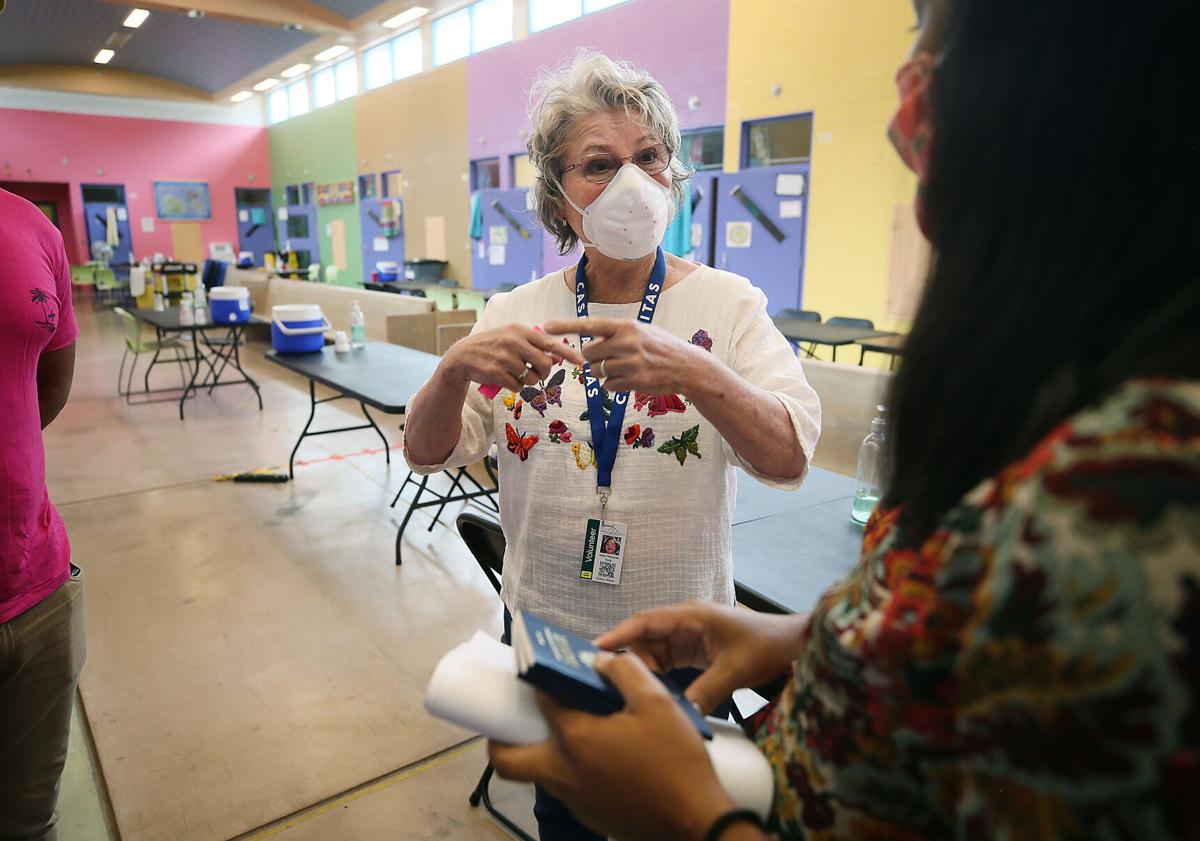

Marjorie King hands out snacks to children leaving the Casa Alitas Welcome Center. The retired educator has been volunteering in the migrant community here since 2012.

So, King joined Casa Mariposa migrant outreach.

That outreach stemmed from when locals saw that migrants were being released into the community with no provisions or assistance. Casa Mariposa volunteers began to meet them, assess their situations, and help them navigate travel schedules. If the migrants were not up for immediate travel, they were taken to a Casa Mariposa shelter to eat, rest and be provided fresh clothing and travel necessities.

King tells of two Chinese women who had slipped from the border wall, suffered leg and spinal fractures, were treated at a Tucson hospital and then discharged in wheelchairs without accommodations. King cared for them in her guesthouse until they were fit to travel.

She also tells of the day, just before Christmas, when some 20 men, women and children were stranded outside the shuttered Greyhound station because highways east were too icy for buses to travel. King took them home. Between her home and her guesthouse, she put them all up — including a newborn infant.

“I never had a more meaningful Christmas,” she says.

Local facilities and Casa Mariposa capabilities, however, got overwhelmed as the Border Patrol flooded Tucson and Phoenix with greater numbers of asylum seekers. On Memorial Day 2014, when ICE flew 400 migrants — mostly women and children — from Texas to Tucson, activists called in the press. That garnered national attention and got them help.

Catholic Community Services stepped in and formalized Casa Alitas.

These days in Casa Alitas, scores of “incredible, wonderful people” are at work. When families are delivered by ICE or the Border Patrol to Casa Alitas, volunteers greet them, help them connect with U.S. families, and explain travel arrangements. The migrants can rest, shower, care for children, and, if necessary, stay the night. They’re given clean clothing and travel bags containing food, water, toiletries, children’s necessities and blankets. They even get small toys for extended trips.

Recalling the controversy when Casa Alitas moved out of the Benedictine Monastery into the juvenile court center — when people complained the setting would be too much like detention — King says, “ they should really see it”: Casa Alitas is welcoming — clean, bright, colorful, full of art.

Another of King’s areas of concern — Tucson’s homeless — also raises local complaints: Why expend so many resources on migrants, they gripe, when there are so many Americans who are homeless and need help?

“But it’s not ‘either/or,’” King counters. “It’s ‘both/and’ — both migrants and the homeless.” Her church, Grace St. Paul, has an active homeless mission, with food, showers and social services. King says their population prefers this to other shelters. “People come because they feel respected here.”

As coordinator of migrant justice at Grace St. Paul, King facilitates and supports the projects of other social justice activists. She praises three parishioners’ work that relates to the church: McCormick, Nancy Meister, and Valarie James, for such efforts as connecting with migrants sheltered across the border, implementing prayer vigils, and creating an embroidery workshop for migrants in the Casa de Misericordia in Nogales, Sonora.

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed citizens can change the world,” wrote anthropologist Margaret Mead, “it’s the only thing that ever has.” Thoughtful, committed citizens, indeed.

So, why do this sort of work?

“As a young traveler,” King says, “I was disturbed by the poverty and suffering I saw.” As an academic, she saw their structural causes. “My earlier understanding enlarged to a profound personal experience of my common humanity with the most vulnerable and least powerful people among us.”

Those, and her faith’s “emphasis on helping the poor, the widow, the orphan, and the stranger” make for a pretty compelling driver.