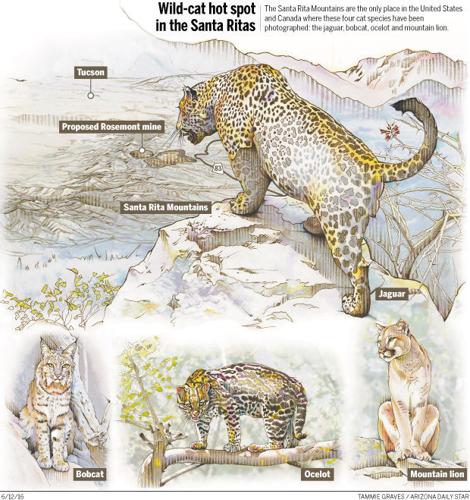

The Santa Rita mountain range, known globally for its birds and arduous hikes, now has another distinction — it’s the only place in the U.S. and Canada where four wild cat species are known to have lived.

This discovery came to light in a new study tracing the paths of jaguars and ocelots across Southern Arizona, particularly in the Santa Ritas. The federally financed three-year study by University of Arizona researchers placed remote cameras at 250 sites across 16 mountain ranges.

At two sites in the northern Santa Ritas, photos captured a jaguar and an ocelot, both endangered species, as well as the much more common bobcat and mountain lion. Both times, all four species were photographed within a 24-hour period, the researchers said.

“It’s very unusual. We had that happen two times on a single camera,” said Melanie Culver, the study’s principal investigator. “Texas has the ocelot. They don’t have the jaguar. In the northern U.S. and Canada they have the lynx, but no ocelot or jaguar. Arizona is really unique. Southern Arizona is really unique.”

Added Susan Malusa, the study’s project manager, “You cannot find four cats anywhere north of Mexico in North America.”

Having the four species shot together within 24 hours is about as close as you can get to having them in the same photo, Culver said.

“You are not going to get jaguars and pumas posing together,” Culver said. “The only way that will happen is if one is trying to kill the other one.”

Their comments came during a wide-ranging interview, in which they also stressed what they see as the biological importance of the lone male jaguar caught in photos and videos 118 times in the Santa Ritas from fall 2012 to June 2015. From June to October, another nine jaguar photos were shot there by remote cameras managed by “citizen science” volunteers after the federal money ran out.

Since then, the animal has dropped out of sight, triggering speculation that he may have ventured back into Mexico.

The researchers also discussed the value of species, such as the Santa Ritas jaguar and the ocelot, that live on the edge of their range. Three ocelots were spotted during the study: one in the Santa Ritas and two in the Huachuca Mountains. One of the Huachuca ocelots also was photographed in the Patagonia Mountains by a private citizen during the study period.

In their conversation with the Star, Culver and Malusa discussed how jaguars and ocelots get around the existing U.S.-Mexico border wall and warned that their passage into the U.S. could be virtually cut off if Donald Trump’s plan to build a continuous wall becomes a reality. They didn’t take a stand on the proposed Rosemont Mine, which would lie near both sites where the four cat species were photographed. But Culver said that, in general, she’d like to see the Santa Ritas’ habitat protected.

The $1 million study, which the Star obtained in draft form through the federal Freedom of Information Act, was financed with $771,000 from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. It was one of several DHS-funded projects aimed at mitigating impacts of the existing border wall. The rest of the money came from the University of Arizona, Culver said.

The study was published June 10 by the U.S. Geological Survey, Culver’s employer. Malusa is a UA research associate.

Here are excerpts from the Star’s conversation with the two researchers:

Q. What makes the Santa Ritas so attractive to large cats?

Culver: It’s their ruggedness and remoteness.

Malusa: It is very rich in prey and has perennial water available virtually all year long.

Q. What about the habitat?

Malusa: The greater part of our detections have been in Madrean evergreen woodland (originating in the Sierra Madre in Sonora and dominated by evergreen oak, juniper and sometimes pine).

Q. How much prey?

A. The study found that of 25 individual species and groups of species photographed by the Santa Ritas’ cameras — the most found in any of the 16 mountain ranges — all but the jaguar itself represented potential jaguar prey.

Q. Before people developed so much of the natural environment, could all four cat species have been photographed in more places?

Malusa: One hundred years ago, when many species were more common and jaguars ranged up to the Grand Canyon, it wasn’t so rare to see four cats. But these days, with many species having much smaller ranges, it’s very unusual.

Q. How can this research help with conservation of these two species?

Culver: It gives us a better idea of the habitat they are using in Arizona, their activity patterns in Arizona and the extent of their range in Arizona.

Q. Can you cite an example?

Culver: There was one instance where one ocelot was going from the Huachucas to the Patagonias and back. That’s pretty significant. It’s a larger area than we expect an ocelot to roam through.

Q. Why does that matter?

Culver: It gives us the incentive to look further into the corridors (that they move through). Because we know without protected corridors we won’t continue to see these animals. Particularly in the case of the ocelot, if those corridors aren’t there, they are not going to be able to use these most northern habitats. The same would be true for the jaguar.

Q. The federal government has built 124 miles of fences and 183 miles of vehicle barriers along Arizona’s 378 miles of Mexican border. Along the entire, 2,000-mile U.S.-Mexico border, the feds have built 652 miles of fences, walls and vehicle barriers. How do the jaguars and ocelots in Mexico get through the barriers?

Culver: In the more rugged areas, the canyons and mountains, what they’ve done is either there’s no wall and they just have towers and night-vision goggles, or they have vehicle barriers, Normandy-style fences that are crosshatched. Those are the areas where large carnivores can still get through.

Q. Donald Trump wants to build a wall along the entire U.S.-Mexican border to ensure that immigrants can’t cross the border illegally. How would that affect jaguar and ocelot movement into the southwestern U.S.?

Malusa: They need movement corridors. There needs to be connectivity. The wall would cause further fragmentation and reduce connectivity. … The animals’ range doesn’t end at a political boundary, at the international boundary. It’s going to stop everything.

Q. When your report came out a few weeks ago, the Center for Biological Diversity said the presence of jaguars, ocelots and species diversity in the Santa Ritas shows that this habitat should be protected. Do you agree?

Culver: I think that area of Southern Arizona has been managed in a way for hundreds of years that has maintained high-quality habitat. Without it, there’s no way these jaguars and ocelots would be able to come up there and make a living at what they do. That is really a credit to the stakeholders that live in that area, the managers and the agencies.

Q. So what should we do now?

A. I would recommend that we continue doing the same thing we’ve been doing for the next 100 years: Keep that habitat in as good a shape as it is today, and not let it get further degraded.

Q. Do you think the information your study gathered justifies opponents’ calls not to put the mine there?

Culver: I think it depends on the footprint of the mine and how that footprint affects the sites that we’ve detected and the habitat overall. I don’t think that exact question is something that we have looked at. That was not an objective of this study.

Malusa; It definitely would change things, undoubtedly. We can’t really look into the future and say exactly how it would change but it would change things.

Q. Switching gears, were you surprised the jaguar stayed in the Santa Ritas so long?

Culver: Pleasantly surprised. You never know what to expect. You could go there for three years and never detect jaguar at all. We consider ourselves very fortunate.

Q. This and the four other jaguars documented in this region since 1996 have been lone adult males. Do these occurrences have any biological importance?

Culver: A lone male animal can be the harbinger of a future population and future breeding. Nonbreeding males, males that strike out in a different direction, they are colonizing new habitat. You get enough nonbreeding resident males and eventually females follow behind. Research on tigers in India has shown this.

Q. But the late scientist Peter Warshall wrote in a 2012 paper that it could take a very long time, at least 45 to 70 years, for female jaguars to come up to the United States from Mexico because female jaguars stay relatively close to their mothers and expand very slowly over time.

Culver: Based on what I know about female movements, they are much more tied to their natal area. It takes a major female to strike out on a long distance. If the Sonoran population is not at its carrying capacity, they never will.

Q. These five jaguars have lived on the northern fringe of the jaguar’s range, the periphery. Does that mean they don’t matter much?

Culver: A peripheral animal does have biological importance. In peripheral populations, you often get unique genetic variation and unique forms of genes. They’re a little different than individuals at the center of the range.

Q. How are they different?

Culver: The forms on the edge, they are likely to be adapted to those different habitats out on the edge, particularly in the northern edge where the climate is more arid. They may be more adapted to conditions like drought and other climate conditions that could happen with future climate change. I would never understate the importance of a peripheral population, from a genetic adaptation standpoint.

Q. Alan Rabinowitz, the noted jaguar biologist, has spent a career trying to save jaguars in Central and South America, but he doesn’t believe the Southwest’s and northern Mexico’s jaguar population is worth the attention it’s getting from some conservationists. He has said that the money and other resources being spent on jaguars here would be better spent elsewhere in areas where the population is abundant but still needs help. Do you agree?

Culver: I respect Rabinowitz very much, but that’s one thing he says I don’t agree with. I have some data on the genetics, the genotypes of the Sonoran jaguars. Pieces of their maternal genomes show that they are just as unique as any jaguar population in every other geographic region — Panama, Venezuela, Costa Rica.

Q. Your report says that in the past 15 years, U.S. jaguar discoveries have returned to occurring at nearly the same intervals as before 1973, after having crashed from 1973 to 2000. Does this make you optimistic for their future in this country?

Culver: Sure, I’m always an optimist. But it all depends on Mexico, and how healthy the population in Mexico is, and that the jaguar corridors in the U.S. and Mexico remain intact. … You can’t separate the jaguars in Southern Arizona and Mexico. They’re all one population.