South-sider Linda Robles describes her last decade as a procession of family illness. She says she’s lost a daughter to lupus and seen the illness strike two of her other seven children. She’s had a daughter and a grandson born with a cleft lip. Last year, her ex-husband was diagnosed with a cancerous kidney tumor.

Now, Robles is on the front line of an impending legal conflict over whether contaminated water has caused these and many other ailments that she and other residents say are occurring there. Robles, who has lived in that area for most of her 55 years, is organizing an effort to gather hundreds of written legal claims alleging that water contamination is causing illness in the area — claims that could ultimately lead to a lawsuit.

Such claims and litigation are nothing new on the south side, where groundwater has been known to be tainted with cancer-causing trichloroethylene since 1981. In the 1990s, two separate groups of lawsuits involving hundreds of residents alleged that TCE in the area’s drinking water triggered massive illnesses, including cancer, lupus, central nervous disorders and birth defects.

In both cases, the residents won financial settlements from Hughes Aircraft Co. and other parties held liable for dumping TCE into the ground as long ago as the late 1940s.

This time, residents are targeting a different compound — 1,4 dioxane. Like TCE, 1,4 dioxane was used as an industrial solvent in the airport area. However, it wasn’t known to exist in the area’s groundwater until 2002. It is considered a probable carcinogen by the Environmental Protection Agency, but efforts didn’t begin to remove it from Tucson groundwater until 2014. By contrast, the removal of TCE from the aquifer began in the late 1980s.

At a community meeting last Monday, hundreds of residents packed a south-side ballroom to hear Robles and an attorney who won well over $100 million in various TCE legal settlements, Richard Gonzales, discuss the past and possible future legal cases. Afterward, dozens stood in line to pick up claim forms. Gonzales, who said he knows little about the current dioxane issue, offered the residents some good cheer when he said, “Nobody gave us a chance, but we won.”

Later, Gonzales, now semi-retired at age 67, said he would offer legal help to Robles and others working on a new case, although he doesn’t plan to formally represent them. Robles says her plan is to sue Raytheon Missile Systems, which merged with Hughes Aircraft in the late 1990s. Because no litigation has been filed, Raytheon has no comment, company spokesman John Patterson said.

But a potential dioxane case is fraught with complexities that didn’t exist in the TCE case and could present obstacles to residents, say Gonzales and another legal experts.

First, residents must prove dioxane caused their illnesses above and beyond any effects from the TCE. “It’s the same as a person getting rear ended twice on two different dates,” Gonzales says. “How do you differentiate your back pain from the first accident versus the second accident?”

Second, residents would have to prove that they’ve been drinking contaminated water in recent years.

It was widely known and heavily publicized that the TCE had polluted 11 Tucson city wells back in the early 1980s. But today, Tucson Water officials insist that generally, no contaminated water has been served to south-side residents since 1981, when those wells were closed.

Robles and other south-siders who have taken out claim forms distrust the city’s assurances. Because of the complexities of Tucson Water’s system of treating, blending and delivering water, Robles is convinced dioxane-tainted water has been served to them.

But the residents know their case must transcend simple mistrust. Robles said she’s already gathered about 400 claim forms from people saying they have various cancers they believe came from the drinking water, and, working with a doctor, she plans to conduct a detailed health study.

In the past two weeks, the residents got potentially good news from state authorities. On April 3, Arizona Department of Environmental Quality official William Ellett emailed Robles that the department has asked the Arizona Department of Health Services to “look into doing a health consultation for TCE and 1-4 dioxane” concerning pollution near Tucson International Airport, and examining the pollution’s possible association with cancer and lupus.

Late Friday, state Health Department spokeswoman Holly Ward said the department is working with Pima County health and environmental officials to determine the best next step.

One possibility would be to bring in the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) to get a better picture of the broader health issues and pathways residents have to exposure of the chemicals, Ward said. The agency, part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, performs public health assessments of toxic waste sites and of contamination-related health impacts.

“We’re discussing with Pima County DEQ and the county department of public health to determine what data do we have and what data do we need,” Ward said. “Do we have enough data to make an assessment, or do we need to bring in ATSDR?”

MAP DOTTED WITH CANCER

Linda Robles recounts her family health issues as she sits in her studio apartment near South Sixth Avenue and West 29th Street. On a wall next to her is a map of the area’s TCE pollution plume from the 1980s, given to her by Rose Marie Augustine, then and now chair of Tucsonans for a Clean Environment, who led much of the effort to get groundwater cleaned back then and is advising Robles today. The map is full of pins showing where cancer cases turned up.

Robles started with 2003, when Tiana Shosie, her daughter by an earlier marriage, was diagnosed with lupus after going to the hospital. “Her kidneys were not functioning,” Robles says now.

She died four years later at age 19 — “she was a beautiful daughter, I miss her dearly,” Robles says.

A year later, Robles’ daughter Clarissa started showing many of the same symptoms, Robles recalls. “She was diagnosed at a very bad state of Class 4 lupus. She had kidney failure. ... She was very weak. She was very scared. Two years ago, she was told she was going to die in three months if she didn’t do the chemo. She did do the chemo, so thank God she is still here,” Robles said.

In 2009, her son Joseph was suffering “horrific” rashes; he was diagnosed with lupus, Robles says. In 2013, her year-old granddaughter Adrina began spells of vomiting, dizziness, rashes and having hair fall out — she was diagnosed with kidney nephritis, Robles says.

And in 2016, her ex-husband Joe, with whom Robles had lived for many years in the Midvale Park area west of Interstate 19, had surgeons remove a large kidney tumor that was later found to be cancerous, Robles says. He has since recovered, but Robles’ 5-year-old niece Mia Flores, who also lives in Midvale, was diagnosed with inoperable brain cancer last December, Robles says. Mia’s teachers at Hollinger Elementary School wrote her mother a letter saying the girl was “doing a lot of baby talking in the classroom and was losing her speech and vision due to the tumor,” Robles says.

It was her granddaughter’s 2012 illness that caused Robles to say “no more,” and begin studying water issues at a public library at the El Pueblo Neighborhood Center. She started attending meetings of the Unified Community Advisory Board, a group of citizens, companies and agencies held potentially responsible for the pollution that is now overseeing the TCE cleanup.

Attending meetings and reading various public documents on the ongoing dioxane contamination got her more concerned, and she started holding public meetings and mobilizing residents to sign the claim forms. She is having the forms sent to the Justice Department because Raytheon is an Air Force contractor.

Two longtime south-siders who picked up the claim forms are Angela Martinez and her aunt, Sharon Flowers. Martinez’s grandmother and Flowers’ mother, the late Marie Sosa, was an early plaintiff in the TCE lawsuits in the 1980s and ’90s.

Sosa also worked for Hughes Aircraft in the 1970s and ’80s, and was later diagnosed with breast cancer and lupus, and had both her breasts removed. A close friend and ally of Rose Marie Augustine of Tucsonans for a Clean Environment, Sosa died in 2012.

Flowers, Martinez, Augustine and Sosa all have lived and Flowers still lives in the Mission Manor area near 12th Avenue and Drexel Road, all within the TCE-dioxane plume area.

Flowers, now 59, also was a plaintiff in the first TCE lawsuit back in the 1980s. Back then, she had thyroid cancer that metastasized to her lymph nodes, and surgeons had to remove muscles on the left side of her throat, she says. A non-malignant tumor “the size of a football” was removed from her stomach in 2012. Today, Flowers says she’s in such constant pain that she can’t work.

Martinez, who turns 37 on April 28, says she drank the water in that area off and on for 21 years. The water had a “yellow tinge to it and tasted funny — I grew up not liking the water very much,” she said.

At 26, she says, she started having irregular menstrual cycles. A biopsy found cancer cells in her cervix. Two-thirds of it was removed. She was told by doctors that she had only a 30 percent chance of having kids, but she has since given birth to three daughters, including the 3-month-old Angela.

She’s also had Graves disease, an autoimmune disease that causes the thyroid gland to be overactive; her thyroid was removed in 2014, she says. Both her parents and a grandfather also had their thyroid glands removed, but when her family conducted a genealogical family history, “No one else in our family had thyroid problems,” Martinez said.

“Me, personally, why I’m involved is for my daughters. They drank this water. I’m not so focused on how it affects me. I’m focused on let’s get this thing cleaned up. My kids deserve a fighting chance,” Martinez said.

LINK TO CANCER NOT CLEAR

One challenge residents face in linking their health problems to dioxane is that it has different health effects and behaves differently from TCE, says a Vermont-based lawyer who also worked on the TCE case. Tony Roisman represented 250 south-siders who got legal settlements over TCE contamination in the 1990s.

Roisman worked with Tucson attorney Sheldon Lazarow against Hughes and two other plane manufacturing firms operating in the Tucson International Airport area. Their settlement award was sealed by the judge, Lazarow says.

Roisman recently settled another legal case elsewhere involving dioxane.

Compared to TCE, he finds dioxane a less well-recognized human carcinogen. The federal government classifies TCE as a known cancer-causing agent and dioxane as a probable carcinogen, Roisman notes.

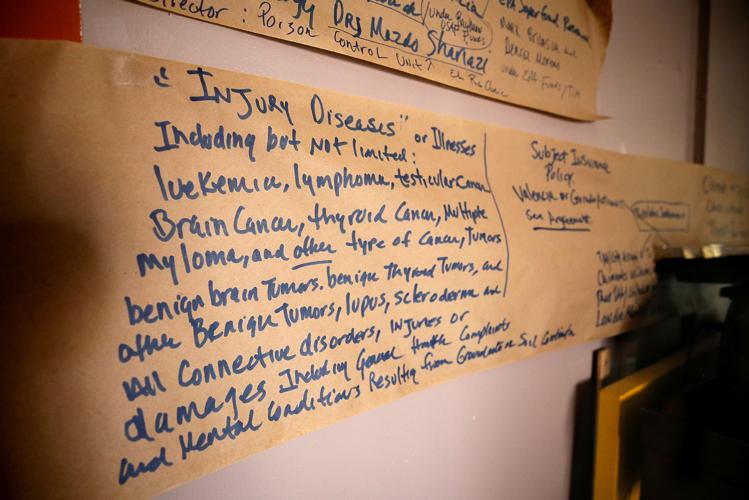

Also, dioxane’s cancer-causing properties are generally limited to the liver and kidneys, he says (it’s also been linked to gall bladder cancers, according to the EPA). TCE has been linked to those cancers and leukemia, lymphoma and multiple myeloma, plus auto-immune disease, Roisman says.

The case against dioxane as a carcinogen is based only on animal studies, whereas TCE has been shown to cause cancer in both human and animal studies, he says.

“Getting experts to testify that dioxane will give people cancers won’t be easy,” Roisman says.

Finally, the compounds’ properties are very different, according to Roisman. TCE typically clings to the soil. Dioxane “clings to nothing,” he says.

“If you drop one gallon of dioxane into the soil on day 1, by day 2, that gallon is gone. ... TCE could be tracked back. For dioxane, that’s a lot harder to do because it’s very mobile. It’s harder to show that people get exposure.”

A challenge that Roisman and Lazarow faced was proving that the south-side residents were actually drinking TCE-tainted water. That’s because contaminated groundwater wasn’t the only groundwater served on the south side, he recalls. The area had a “whole network” of public and private wells.

The lawyers had an engineering professor track the sources of drinking water. He found that of 16,000 people who signed up for the litigation, “only 1,000 had water from a contaminated well,” Roisman said. After going through medical records to find people with cancers traceable to TCE, the number of plaintiffs was whittled to 250, he says.

WATER CLEANUP

For dioxane, the story is somewhat different.

After its discovery in 2002, Tucson Water first blended it with clean drinking water from the Avra Valley to reduce the dioxane content. The Tucson Airport Remediation (TARP) air-stripping project that has cleaned TCE from the water couldn’t pull out the dioxane.

During that time, it was in the TARP-treated water at levels of about 1.5 parts per billion, compared to a recommended EPA standard of 3 parts per billion. But in the early 2010s, EPA knocked down the recommended limit to 0.35 parts per billion. That forced Tucson Water to build a new plant, open since January 2014, to treat dioxane to levels below what equipment can detect — 0.1 part per billion.

Today, Tucson Water Administrator Jeff Biggs says that the TARP water has been delivered to about 60,000 customers living downtown, on the north side and on the west side along Silverbell Road north to El Camino del Cerro.

“TARP water was never delivered to south-side residents,” Biggs said.

But a Tucson Water map shows a small slice of the area between 22nd and 29th streets west of South Sixth Avenue getting that water. Told of that, Biggs said the department’s position is actually that no TARP water has been served to the area of the original TCE pollution plume. Its northern edge lies just north of Irvington Road.

“We just need to be more clear when we talk about that,” Biggs said.