When Ed and Margo Diego decided to invest in a four-bedroom fixer-upper near Randolph Golf Course earlier this year, they combed through the neighborhood’s property restrictions to find out what kind of renovations they would be allowed to make.

What they discovered instead was an ugly relic from the past.

Included in the covenants, conditions and restrictions sent to them by their real estate agent was a rule — long since outlawed, yet still part of the 76-year-old document — prohibiting the home from being owned or occupied by “any person of African or Negroid descent.”

Ed Diego is Hispanic by way of Puerto Rico. His wife is African American. Both of them felt targeted by what they read.

“It didn’t come with any warning,” said Diego, an electrical engineer for Raytheon. “We both took a gasp. We were like, ‘There’s no way this is real.’”

Legally, it isn’t. Race-based housing restrictions were ruled unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1948 and explicitly outlawed as part of the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

But throughout the first half of the 20th century, discriminatory covenants were written into the founding documents of countless subdivisions nationwide, Tucson included.

In a startling number of cases, those racist old rules are still on the books. And more than 50 years after they were rendered illegal for good, they continue to show up in the piles of documents people like the Diegos are required to sign when they buy a home.

“For certainly any person, but especially for people of color, I think that can be a particularly traumatizing experience,” said Jason Jurjevich, a professor and population geographer at the University of Arizona.

Jurjevich is leading a new research initiative aimed at identifying Tucson neighborhoods that still have racist restrictions buried in their covenants, conditions and restrictions, also known as CC&Rs.

Initially at least, the Mapping Racist Convenants project will focus on subdivisions established between 1930 and 1951, a period of rapid growth in Tucson when race-based housing discrimination was so commonplace it was featured as a selling point in newspaper ads for new developments.

By next summer, the project team hopes to unveil an interactive online map that will allow Tucsonans to not only see if their neighborhood was once restricted by race but read the actual documents, “which they might or might not remember signing,” Jurjevich said.

Hard to find

The researchers have their work cut out for them.

Jurjevich said some 1,500 subdivisions were created in Tucson between 1912, when Arizona became a state, and 1950. Finding which ones excluded people based on race will involve working closely with the Pima County Recorder’s Office to scour through thousands of old paper records preserved on microfiche.

In that way, he said, racist covenants pose a much greater challenge to researchers than the discriminatory housing practice known as redlining, which produced actual maps showing neighborhoods that were denied loans or insurance based on their ethnic makeup.

By contrast, “racist CCRs are buried in archival records that are often not digitized,” Jurjevich said, “which is why I think there’s only been a handful of projects across the country” like this one.

The effort here will build on work started in early 2021 by UA Librarian Emerita Chris Kollen, who was inspired by other such mapping projects in Colorado, Minnesota, Washington state and Washington, D.C.

She said she spent a great deal of time at the county recorder’s office, where she eventually unearthed about 30 examples of racist covenants from spools of digitized microfilm she said is not indexed very well.

The documents are “not easy to find,” said Kollen, who is now part of the project team. “I only went through a very small percentage.”

It’s far too early to say for sure, but Jurjevich thinks there could be hundreds of subdivisions in Tucson with discriminatory restrictions tied to them.

“Our early research suggests that African Americans and Asian Americans were targeted in particular. And there was also language that generally excluded anybody who was not white,” he said. “We’re also finding that there were covenants that excluded Jewish individuals and covenants that excluded women from owning property. I think there’s a lot more that we potentially will be adding to the story.”

Montecito Street at Alvernon Way in Tucson. Ed Diego and his wife were looking to buy a home on the street.

‘A dead letter’

So why do these old rules still linger, decades after they were cast off by Congress and the courts?

“Nobody really wants these things, but they’re hard to get rid of,” said Carol Rose, a professor emerita of law at both the UA and Yale University.

In 2013, Rose co-authored a book with Richard R.W. Brooks called “Saving the Neighborhood: Racially Restrictive Covenants, Law, and Social Norms.”

She said CC&Rs amount to private contracts among the property owners of a given area, so they’re largely out of the purview of local governments. In most cases, there are processes in place to alter or remove certain covenants, but “it’s complicated to do, so people don’t bother,” she said.

That appears to be especially true of discriminatory covenants, which have been widely left in place because they have already been rendered meaningless under the law.

“It’s an affront, but it’s an affront that doesn’t have any teeth,” Rose explained. “They’re a dead letter. They are in people’s CC&Rs and deeds, but they are non-enforceable.”

They can still inflict emotional damage, though, as Jurjevich learned personally about a year ago.

He and his husband, Charles Walker, bought a house in Encanto Park, a subdivision of the Miramonte neighborhood near Broadway and Country Club Road.

As part of the closing process, their real estate agent sent them the property restrictions along with a warning: “She said, ‘I want to let you know that they’re racist,’” Jurjevich recalled. “My husband is African American, and she wanted us to know that we were going to need to technically sign off on these things.”

The list of rules recorded in 1947 specifically targeted people of “African or Asiatic descent” and anyone else “not of the White or Caucasian race,” prohibiting them from living in the subdivision unless they were employed there as domestic servants.

Like other CC&Rs from that time, the Encanto Park rules allowed for changes to be made with written consent from at least 75% of homeowners. The one exception was the restriction on race, which “shall be perpetual,” the document stated.

When Jurjevich pointed all this out to the title company, “they basically said, ‘Just sign the document, because that covenant is illegal,’” he said.

He and his husband went through with the purchase anyway because they weren’t in a position to walk away from it, Jurjevich said, but it left him wondering just how common an issue this might be.

“How many other couples are having to go through this situation where they have to sign a set of CCRs that contain this language that they’re opposed to?” the geographer said.

“The personal nature of the experience, combined with my academic interest in thinking about the larger arc of institutional discrimination for people of color in this country, sort of set me on this path to formalize this research project.”

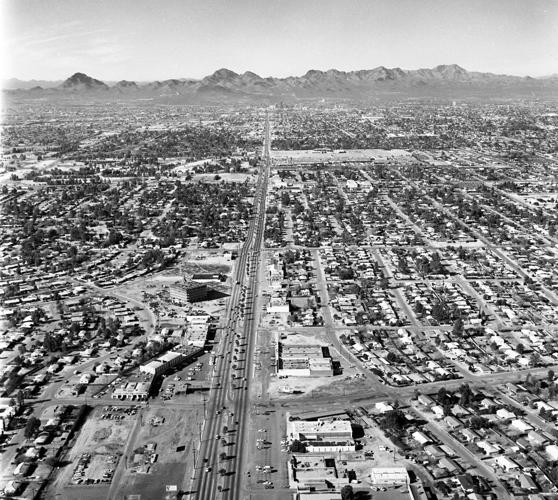

Broadway Road looking west from Swan Road, Tucson, in 1968. The wide Venice Stravenue (a Tucson street invention) is the street visible in foreground. The Midstar Plaza is at left. The mid-rise office building at 4400 E. Broadway is under construction at left.

Hard to believe

The work is being funded by the University Libraries’ Digital Borderlands program through a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Jurjevich and company are planning an official launch of the project in mid-November with an informational event on the UA campus hosted by the African American Museum of Southern Arizona.

The fledgling museum is a collaborator on the mapping initiative, along with the Tucson Chinese Cultural Center, the Tucson Jewish Museum & Holocaust Center, the Southwest Fair Housing Council and the city of Tucson’s Housing and Community Development Department.

African American Museum co-founder and executive director Beverely Elliott said her role so far has been to connect researchers with people in the Black community who have experienced housing discrimination in Tucson in the past.

She didn’t have to look very hard. “The first five people I reached out to said, ‘Yeah, that happened to us,’” she said.

Elliott and her husband, UA basketball legend Bob Elliott, have experienced it, too.

In the late 1970s, when he was still playing in the NBA, the Elliotts decided to buy a condo in a new development near Prince Road and Campbell Avenue, only to discover that the property had decades-old racist restrictions tied to its deed.

“I was just stunned to find out those things were still going on in the ‘70s,” Elliott said. “The homebuilders helped us with it. They were instrumental in letting us know that wasn’t going to hold water.”

But discrimination certainly didn’t end with the outlawing of racist housing restrictions. For decades after that, Elliott said, people of color still found themselves being discouraged — sometimes subtly, sometimes openly — from living in certain parts of town.

“That has happened to a few African American friends that we’ve known, and sadly it has stopped people from wanting to live here,” she said.

In this 1929 photo, Hi Corbett Field, bottom, can be seen with the newly developed Colonia Solana and El Encanto Estates to the north. To the east of El Encanto is the El Conquistador Hotel and its water tower across the street.

Change is coming

Jurjevich hopes the Mapping Racist Covenants project will serve as a catalyst for change.

He said similar efforts in Washington state and Minnesota have led to legislation that makes it easier for neighborhood associations and individuals to withdraw from racist covenants or eliminate the language altogether.

Rose said California has also taken action on the issue, and she expects more states to follow suit in the coming years. Right now, she said, the respected Uniform Law Commission is working on a model statute for state legislatures to adopt to streamline the process.

In a possible hint of just how widespread the problem might be in Tucson, the Diegos recently discovered that the racist CC&Rs they received in June were actually sent to them in error. The house they were trying to buy was in the San Gabriel subdivision, across Alvernon Way from Randolph Park, but the covenants they got instead came from El Cortez Heights, a neighborhood near First Avenue and Grant Road.

As it turns out, though, San Gabriel also has discriminatory restrictions written into its CC&Rs from 1935. Only the wording is different.

The Diego family eventually ended up buying a much larger house on five acres of desert off Valencia Road, in a part of Drexel Heights with no homeowners association. The place needs some work, but it has “a lot more potential,” Diego said.

It was built in 1968, the same year as the Fair Housing Act. The family might never have found it if not for the nasty surprise that turned up in the paperwork for the other house they wanted to buy.

“I guess it was a lucky break,” Diego said.