The final days of 2025 left wildlife lovers seeing spots.

Remote camera footage released during the last two weeks of the year showed two different endangered ocelots roaming the mountains of Southern Arizona, including an especially unusual sighting in the Santa Rita range south of Tucson.

That rare spotted cat was featured in a photo released on Dec. 23 by the University of Arizona Wild Cat Research and Conservation Center, which operates roughly 100 wildlife cameras from the Baboquivari Mountains on the Tohono O’odham Nation to southwestern New Mexico.

Researcher Susan Malusa, director of the nonprofit center, said the lone picture, captured by one of those motion-activated cameras in late July, represents just the second confirmed ocelot sighting in the Santa Ritas since the late 1800s.

“It’s just standing there perfectly for the camera. It’s a nice image,” Maulsa said. “We’re very excited about this detection.”

An endangered ocelot wanders through the Santa Rita Mountains south of Tucson in a wildlife camera photo captured in late July and released on Dec. 23 by the University of Arizona Wild Cat Research and Conservation Center.

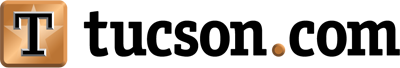

Based on an analysis of the cat’s spots and other distinctive markings, experts believe it is the same, well-traveled male ocelot that was caught on remote cameras twice in 2024 — first in June in the Atascosa Mountains west of Nogales by researchers from the Phoenix Zoo, then in July in the Whetstone Mountains by the Center for Biological Diversity.

A comparison of markings shows the same wild ocelot caught on camera in the Atascosa Mountains and the Whetstone Mountains of Southern Arizona in 2024. That same cat was photographed again in July of 2025 in the Santa Rita Mountains.

Those mountain ranges are roughly 50 miles apart, with such barriers in between as Interstate 19, the Union Pacific Railroad tracks and Arizona Highway 83.

The ocelot eventually made its way to the Santa Ritas, where Malusa said it wandered through an area the center has been monitoring for years in a remote canyon close to available water. For the cat’s protection, she declined to reveal the specific location.

A new 'boss?'

Malusa said the center’s dedicated team of volunteer researchers is now checking other cameras in the Santa Ritas and elsewhere in hopes of finding other images of the ocelot and maybe some clues about its route between mountain ranges.

“That’s part of the work, right? Where are the most likely spots for these (travel) corridors,” she said.

They also plan to return to the site where the cat was photographed in search of scat that can be used to analyze the animal’s diet and genetics.

The detection comes 12 years after the only other ocelot sighting on record for the Santa Ritas. That individual was documented by the center seven times from 2013 to 2014 and hasn’t been seen since.

The other recent footage of an ocelot was recorded in the Huachuca Mountains on Oct. 23 and released on Dec. 28 by Vail wildlife videographer Jason Miller.

An ocelot's eyes reflect the light from a remote trail camera in a screenshot from a video captured on Oct. 23 in the Huachuca Mountains by Vail wildlife videographer Jason Miller.

It shows a different cat slinking out of the dark and into a forest clearing, its eyes lit up by the light from the motion-activated camera.

At first glance, Miller figured it must be Li’l Jefe, an ocelot that has been living in the Huachucas — and showing up on trail cameras — for so long that conservationists gave it a nickname in 2019.

“I thought it was Li’l Jefe, because that’s the only (ocelot) I’ve ever captured and that’s the only one known about in the Huachucas,” he said. “But this isn’t Li’l Jefe. This one is brand new.”

Second big score

Russ McSpadden from the Center for Biological Diversity thinks so, too.

“I’m looking at images lined up for pelage spot analysis. It’s clear the Miller video shows a cat that is unique,” said McSpadden, a Southwest conservation advocate for the Tucson-based environmental advocacy group.

He couldn’t say for sure whether this animal has been previously detected in Mexico or by other groups with cameras in the Huachuca Mountains, including U.S. Customs and Border Protection. “But based on publicly available information, this does appear to be a previously unknown ocelot,” he said.

That would make this just the seventh different ocelot documented in Arizona since 2009.

“That’s awesome,” said Miller, who now operates about 20 remote cameras at locations across Southern Arizona, half of them in the Huachucas.

He released his potentially historic, 15-second clip on his YouTube channel, Jason Miller Outdoors, as part of a collection of recent sightings that included mountain lions, deer, turkeys, coatis and a bear trying to bathe in a small springpool.

Miller previously made headlines a year ago, when he was the first to publicize images of an endangered jaguar that had not been documented in Arizona before.

Miller said his recent ocelot video was captured at the exact same location as his jaguar footage from Dec. 20, 2023.

“This has happened to me twice now,” he said. “I’m not complaining.”

Vail videographer Jason Miller used a remote camera to capture this 2023 image of an ocelot nicknamed Li'l Jefe that has been roaming in the Huachuca Mountains for at least a dozen years. Now Miller has caught a different ocelot on camera in the same range.

But as excited as Miller is about the possibility of a new ocelot roaming the Huachucas, he said it makes him worry about the elder statesman of the mountain range about 90 miles southeast of Tucson.

“Does this mean Li’l Jefe isn’t around anymore?” said Miller, who last caught the old cat on camera in 2023. “And if he is, is this (new) cat going to compete with him?”

Bittersweet sight

McSpadden has bigger concerns. He said ongoing border wall construction and major mine developments in several Southern Arizona mountain ranges threaten to drive ocelots and jaguars out of the state for good.

He points to recent video of border wall contractors blasting hillsides in Coronado National Memorial, where the international boundary crosses the southern slope of the Huachucas, so they can erect 30-foot-tall, steel-bollard barriers through federally designated jaguar habitat and a key wildlife corridor for ocelots.

“Spotted cats keep showing up in Arizona thanks to decades of conservation efforts. That’s proof positive that the sky islands are critical habitat for these intrepid, elegant felines,” McSpadden said. “But if animals that require vast, intact, cross-border landscapes can still move through here, our responsibility is to do more than marvel. We must not be the generation that breaks the last usable paths for jaguars and ocelots with monumental border walls and massive mines.”

An image captured in March by a Customs and Border Patrol remote camera shows a jaguar roaming the Huachuca Mountains. The Center for Biological Diversity got the photo through a public records request, but efforts to enhance the image enough to identify the jaguar by its distinctive spots were unsuccessful.

Ocelots are roughly the same size as bobcats, with rounded ears, longer noses and sleeker bodies.

Fewer than 100 are thought to remain in the U.S., nearly all of them at the southern tip of Texas. They have been protected under the Endangered Species Act since 1982.

Southern Arizona lies at the northernmost edge of the cat’s native range, which includes much of Mexico, Central and South America.

Malusa described them as “very, very hard to monitor,” because they are so much smaller and more elusive than Arizona’s other famously rare spotted cat. “A jaguar will be a bit more bold when it moves across the landscape,” she said.

All of the ocelots recorded in Arizona over the past 15 years have been males, Malusa said. These lone wanderers are probably dispersing northward from populations in Sonora, Mexico, in search of new territory, just as their much-larger, jaguar cousins occasionally seem to do.

“We’re aware of a breeding population (of ocelots) fairly close to the border in Mexico,” she said.

The animals wouldn’t be here if they weren’t finding what they need to survive. “The presence of these cats reflects the broader ecosystem health and connectivity,” Malusa said.

That’s why McSpadden described these latest sightings as “bittersweet.”

“We may be the last Arizonans to share mountains where jaguars and ocelots still roam,” he said. “I think history will judge us as selfish, small-minded and short-sighted if we fail to protect this rare, wild freedom.”