Editor’s note: This is Chapter 2 in a 3-part series. Head here to read Chapter 1, The Crash, and Chapter 3, Blame.

Doctors at Tucson’s only top-level trauma center had just minutes to figure out which one of Norma Santos Trujillo’s many injuries was most likely to kill her first.

Dr. Terence O’Keeffe and more than 20 members of his staff were waiting for Norma in Trauma Bay 6 of Banner-University Medical Center Tucson at 7:41 p.m. on April 19 when she arrived by ambulance.

Norma, a 32-year-old mother, athlete, artist and medical assistant, was a “trauma red” — a designation reserved for the sickest patients coming into the emergency department.

She had lost her right leg, was in shock from blood loss, and the impact of the crash had disconnected her skull from the bone and ligaments of her spine.

Her pelvis and vertebra had fractures. She was bleeding between her skull and the membrane covering her brain. Her left leg was still attached, but barely. It would need to be amputated. Her left ear had been sliced off, and one of her kidneys had stopped working.

The hospital was throwing all its available resources at Norma, who had been pinned between a car and an SUV. The crash happened on Tucson’s south side as Norma helped a stranded motorist — a stranger — to push his stalled SUV.

The car hit her with such force that it severed her legs above the knees and then pushed her onto the road and trapped her underneath the vehicle, severely burning her chest, her right hand, arm and shoulder.

“If we hadn’t been careful and had just yanked her head around, we would have killed her,” said O’Keeffe, who is the hospital’s interim trauma chief.

Trauma doctors are accustomed to seeing people who have been horribly injured in vehicle crashes. But getting a patient who had both legs cut off in a trauma remains rare, O’Keeffe said.

“It would happen once every couple of years at most,” he said. “In the nine years I’ve been here, this has happened less than five times. And we see 4,500 trauma patients per year.”

“Last-ditch attempt”

Using an algorithm called ATLS — Advanced Trauma Life Support — trauma doctors looked at three key factors known as the ABCs: airway, breathing and circulation. For Norma, circulation was the biggest problem. All the blood she had lost was what would kill her first, the trauma team determined.

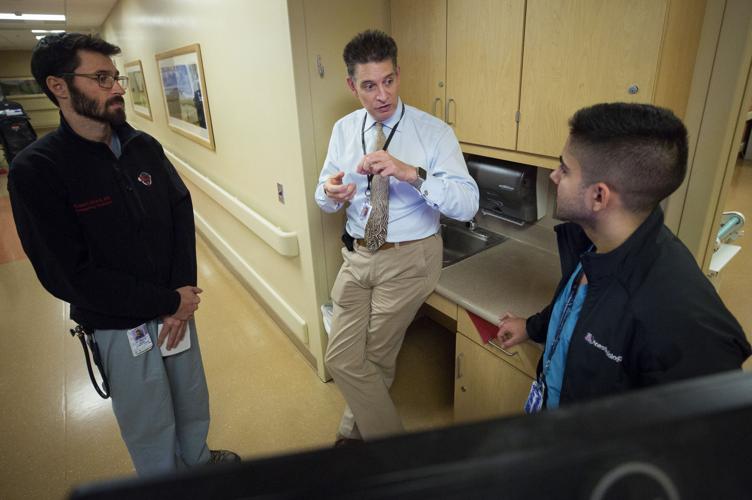

Dr. Terence O’Keeffe, center, talking with medical residents Russell Means, left, and Kayuen Farshed, had to decide how to first treat Norma on April 19.

“In her case, she was talking. She was breathing, but she was clearly in hemorrhagic shock from all the blood that she had lost,” O’Keeffe said.

The hospital activated its “massive transfusion protocol,” which is for people who have lost excessive amounts of blood and is employed for fewer than 5 percent of patients at the trauma center, O’Keeffe said.

O’Keeffe knew it was important to get Norma into the operating room, and to put her on a breathing machine. But first he focused on getting all available blood products plus fluids to get “volume” into her before putting her under anesthesia.

“The other thing I focused on was to make sure the tourniquets were arresting the bleeding on her thighs,” he said.

“And then I immediately picked up my phone and called the orthopedic doctors and said there is a lady here who was very severely injured, and we are going to take her to the operating room, but she needs to have her legs more formally amputated.”

She was in the operating room within 11 minutes of arriving.

“She wasn’t going to get a definitive operation at that time. We were just going to control the bleeding, control the contamination and then get her up to the ICU and get her to do better,” O’Keeffe said.

While orthopedic surgeons Dr. Jason Wild and Dr. Christina Boulton were completing the amputations of Norma’s legs, including cleaning dirt out of the wounds, Norma’s heart stopped.

She “coded” — went into cardiopulmonary arrest — three times while still on the operating table.

“We tried really hard. She arrested on the table. There wasn’t much we didn’t throw at her,” O’Keeffe said.

“She started having real difficulty breathing, probably related to the blood we transfused, or maybe from her initial injury.”

He speculated that the burns on Norma’s chest could have constricted her breathing.

“Her lungs started to fill up with fluid — frothy, pink fluid. It was because of that, and the fact that she was hypoxic (deprived of oxygen) that she arrested,” he said.

Doctors resuscitated Norma using chest compressions and medication. By the third time she arrested, O’Keeffe decided to use what he calls a “last-ditch” attempt.

“I was very determined she wasn’t going to die on us there and then,” he said.

“When patients have high pressures in their lungs, one of the things you can do to help that is to open their abdomen. It gives the lungs more room to expand and can actually help the patient ventilate.”

Whether it was opening up the abdomen, or something else, Norma improved.

“To code three times, your chances of survival are low. That is a miracle right there,” O’Keeffe said.

Devastated

In a waiting room at the hospital, Norma’s large extended family gathered, made a large circle and prayed.

“I have never seen my parents this devastated,” said Norma’s eldest sister, Nayelly Santos, 40.

Norma’s brother Carlo, 37, had been at home watching sports on television that night when his father called.

“I thought it was a regular car accident. I did not know how tragic it was until I got to the hospital,” said Carlo, a construction worker. “I started yelling, cussing and screaming. My world changed.”

Carlo didn’t sleep for 24 hours — “the most horrible, longest 24 hours of my life,” he said.

Norma bears a scar on the back of her neck where plates, titanium rods and screws were put in place to reattach her spine to her skull.

Norma’s husband, Michael Trujillo, didn’t sleep, either. He can only remember short moments from the first couple of days, when every surgery felt like another bad thing was about to happen and that he’d have to prepare for the worst, again and again.

“For a long time I was thinking my kids aren’t going to have a mom. What am I going to do? What are they going to do?” he said. “It felt like you’d see in a movie. I didn’t understand how this could happen to the kids, to me and to my family.”

In most patients, the type of spine injuries Norma suffered “aren’t compatible with life,” said Dr. Shyam Shridharani, an orthopedic spine surgeon who operated on Norma three days after the crash.

Shridharani said he had a lot of conversations with the ICU team before going ahead with a high-risk surgery to reattach Norma’s spinal column to her skull with plates, two titanium rods and screws. Although the surgery could kill her, so could her injury, he said.

“Multiple doctors said there was a very high chance she would not survive in those first few days,” Shridharani said. “We all agreed we were going to do everything for her, which is what her family wanted.”

Doctors told Michael his wife was at risk for outcomes ranging from quadriplegia to death. If she lived, no one knew whether she’d have cognitive deficits, either. Everything was one day at a time. He often felt like all he did was sign consent forms.

“I haven’t had very many people who have arrested that many times on the operating table who I’ve brought back with full neurological recovery, especially considering everything else that is going on,” O’Keeffe said of Norma. “You may not get enough blood flow to your brain so you can get brain damage. … If this had been a 60- or 70- or 80-year-old they would have never survived.”

Wendy Miller, a physical medicine and rehabilitation doctor, examines the burns on Norma’s arm as her husband, Michael, watches during a home visit.

In addition to her leg and neck surgeries, Norma had deep third-degree burns to her right arm, shoulder and abdomen area that required grafts from skin that surgeons took from her back.

She required screws to fix her broken pelvis and lost one of her kidneys.

“It was mind boggling,” Michael said. “She fought through a lot.”

“I need you”

Norma’s health was covered by Michael’s University of Arizona insurance plan with UnitedHealthcare. But Michael had no idea how much would be covered, and how much money the family would have to pay out of pocket. They’d never had to use their insurance for hospital stays, other than when they had their children.

A friend set up a GoFundMe Account. Norma’s sister Nayelly organized two car washes to raise money. Some of Michael’s co-workers donated their sick leave so that Michael wouldn’t have to worry about missing work, and they also took up a collection of $1,000.

Michael’s family, Norma’s parents and a large group of her siblings and their spouses — plus her 17 nieces and nephews — all pitched in. They brought home-cooked meals to the hospital, brought Michael changes of clothes and took care of Michael and Norma’s children.

“Michael is one tough dude. He’s more man than I would have ever thought,” said Carlo, his brother-in-law.

As Norma recovered in the hospital, her children — 10-year-old Josslyn and 3-year-old twins Kaleb and Dean — made gifts with encouraging words.

“It was this crazy, beautiful family,” Michael said. “Everyone was so concerned. We’ve always been that way as a family, but we weren’t getting together as much as before. Her whole family was taking care of me.”

Relatives also brought the three Trujillo children — 10-year-old Josslyn and 3-year-old twins Kaleb and Dean — to the hospital.

Michael debated what to say to his kids, especially Dean and Kaleb.

“I remember the boys saying, ‘Why are you crying, Daddy?’” Michael said.

Josslyn was quiet and didn’t ask many questions. Michael did his best to hide his emotions from Kaleb and Dean. Finally he told them “Mommy had been hurt by a car” but that she’d be OK.

“Don’t worry,” he assured them.

In reality, Michael was terrified. During the first week, Norma’s eyes opened but she showed no sign of recognizing anyone and wasn’t moving on her own. Michael wasn’t sure she could hear or understand him, but he sat by her bed and held her hand.

“If you pull through, I just need you to fight and live. I will do everything else,” Michael told her. “I know you can do this. I promise you a great life. I need you.”

Then Josslyn saw her mom move her hand. No one believed her at first, but then Norma did it again.

“Not today, Satan”

Norma began blinking her eyes once for “no” and twice for “yes.”

She recognized family members, moved her arms and tried to pull out her breathing tube because she wanted to talk.

As soon as she seemed aware, Michael told Norma that doctors couldn’t save her legs. Norma, though woozy from medication and surgeries and unable to talk, understood. She cried when he told her, but Michael said he was the one who shed the most tears about it.

Michael began recording videos of Josslyn and the twins and showing them to Norma. She was the most active when she saw those videos. Her eyes would get big, and she’d squeeze Michael’s hand.

As children, Nayelly, Norma and their other sister, Reyna, used to listen to Whitney Houston’s “Greatest Love of All.” As Nayelly played it in the hospital room, tears rolled down Norma’s cheeks.

“The guy upstairs knows you have a good heart,” Nayelly told her. “You got a second chance at life.”

Norma’s 16-year-old niece Vanessa Marin had been with her the night of the crash. She couldn’t bring herself to visit Norma in the hospital for a week and didn’t go back to Desert View High School, where she was in her junior year, until May 1.

“I feel like I should help,” was one of the last things Norma said to her niece, Vanessa Marin, before stepping out of the car to help a couple push their stalled SUV out of the road.

She was having trouble sleeping and told her mother they could no longer drive through the Campbell and Irvington intersection.

“At the hospital they told us not to cry in front of her. I told her, I loved her and kissed her on the forehead,” Vanessa said of visiting Norma for the first time.

“I was fine when I was in there, and I said, ‘She does look good,’ but outside the ICU I broke out crying.”

As each day passed, Norma made progress. Notes from her multiple surgeries and procedures began to show a pattern: “Patient tolerated the procedure well with no immediate complications.”

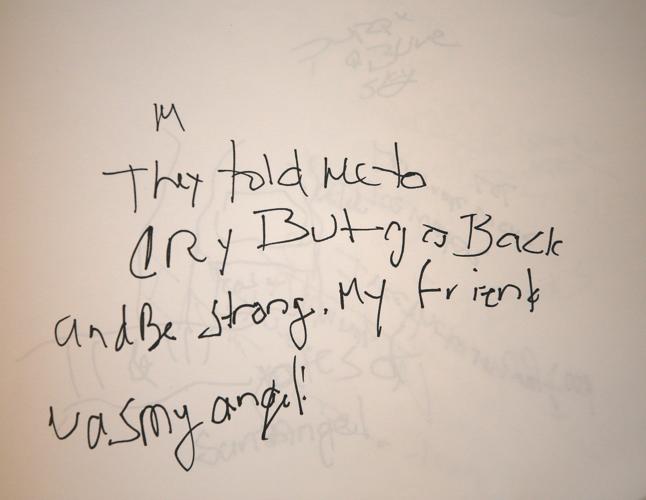

With her vital signs improving, Norma’s family gave her a sketchpad — she loves to draw and once worked as an art instructor. She used the pad to shakily write out messages to her family.

“I saw heaven and my grandpa and two friends. They didn’t let me in,” she wrote in one message. “No keys. Not today,” she wrote.

Norma used a sketchpad to communicate for a couple of weeks and wrote, “They told me to cry but go back and be strong. My friend was my angel.”

One of Norma’s brothers gave her a shirt that said: “Not today, Satan.” She loved it. She wrote that she was grateful to get a second chance at life.

“We know every person is an individual, so it’s hard to predict,” said Dr. Arpana Jain, the surgeon who treated Norma’s burns and leg wounds. “But she beat a lot of odds.”

Nunca Te Rindas

Michael kept friends and family updated on Norma’s progress by text message and social media. She had good and bad days.

When health providers changed the dressings on her burns, it felt like they were tearing off her skin. The pain, she said, was excruciating.

She was devastated to learn her burns destroyed the tattoo on her inner right arm depicting three birds, representing each of her children.

However, she was thrilled that the tattoo she got on her left upper back the night before the crash was still intact. It says “Nunca Te Rindas,” which means “never give up.”

Her grandfather often said “nunca te rindas” to Norma when she was a child. She was so much smaller than her siblings and often struggled to keep up.

Norma suffered third-degree burns on her upper body and along her right arm when she was pinned under the car.

Norma didn’t remember anything about the crash, but family members had been filling her in. On one occasion, she wrote Vanessa a note saying she wished she never got out of the car to help push the SUV.

By the end of May, still in the hospital, she was able to breathe on her own. Her trademark high-pitched voice had become a low whisper, but she was able to speak.

“One time I did completely lose it. I cried for two hours. Nothing specific triggered it,” said Michael, who lost 20 pounds as he kept vigil at the hospital. “I was terrified to sleep or leave.”

Though she didn’t remember the crash, Norma did recall that about a month before it happened, she had moved out of the house she shared with Michael and her children. She knew there was a chance their marriage wouldn’t survive.

“This is your opportunity to leave,” she told Michael one day in the hospital, shortly after her breathing tube was removed.

“No,” he replied.

“You are crazy,” she said.

Around that time, Norma had to go in for another surgery. Her skin graft had become infected, extending her hospital stay.

“Her injuries — everything together — made her body very weak in terms of overall fighting infection,” Jain said. “Her wounds suffered multiple bouts of infection.”

Though the infection was worrisome, Michael was feeling hopeful. He noticed that when Jain talked about the surgery, she said, “once she gets through this surgery” rather than “if she gets through this surgery,” which he had been so accustomed to hearing.

Norma was going to live.

Josslyn’s videos, which Michael played for her almost every day, became increasingly spirited.

“You are the glue of this family, Mom. You are so beautiful,” Josslyn said in one video.

“You are my Wednesday, my hump day, keeping all our days together,” she said in another.

Willpower

Doctors, nurses and others at Banner-University Medical Center Tucson were buoyed by Norma’s progress and by the fact that she could be treated locally. Five years ago she would have most likely been transferred to Phoenix due to the lack of a Tucson program for serious burns at that time.

Since 2012, the hospital had hired two specialized burn surgeons, including Jain, and had built its program to a point where very few burn patients need to go to Phoenix for care anymore.

Also, the proximity of the crash to Banner-UMC may have saved Norma’s life. Had the crash happened in a rural area miles away, she likely would not have survived, O’Keeffe said.

“This is exactly why trauma systems exist. It is to save young, fit, healthy people who can then go on to get back to work and contribute,” he said.

Norma works on her upper body strength during a rehab session with Janelle Borg, a physical therapist, at HealthSouth Rehabilitation Institute of Tucson.

But Norma’s doctors say it wasn’t just her care that got her through. Her family support was tremendous. Moreover, Norma was healthy before the crash. She often went for runs to relieve stress and has always been avid about fitness.

Her body was healing itself. Her left ear, which had been sliced off and sewn back on, was black for weeks. Toward the end of her hospitalization, it turned pink.

Other than losing a kidney she suffered no internal organ damage, and except for some chipped teeth, her face looked exactly the same. Her head bleed had been controlled, and though she was forgetful, she did not seem to have any cognitive damage.

“She has this willpower to get better,” Jain said. “You tell her something, and she follows through. At one point I told her to cut down on her pain medication. Lo and behold, she did.”

Rehab

Norma was discharged from the hospital to HealthSouth Rehabilitation Institute of Tucson on June 6. She had a lot to work on — her burns prevented her from lifting up her right arm, and she could no longer sit up on her own. Physical therapists helped her to work on her arm and core strength with four hours or more of daily therapy.

Norma tries wheeling herself up a ramp for the first time during a rehab session with physical therapist Janelle Borg at HealthSouth Rehabilitation Institute of Tucson.

“A lot of it as an amputee is to take back control,” HealthSouth physical therapist Janelle Borg said.

Norma had become weak from being in bed for so long, and her balance had changed. Her center of gravity had moved higher on her body.

Her spacious room quickly filled up with balloons, flowers, family photos, and artwork by her daughter, Josslyn. Her mother, Carmen Santos, was constantly there, as was Michael. Their twin boys began visiting and called Norma’s wheelchair her “car.”

As she went through physical therapy, Norma got more comfortable with the remainders of her legs. She laughingly likened them to turkey legs from the Renaissance Festival.

Increasingly, she referred to what was left of her legs as her “nubs.” After a few days in HealthSouth she realized she could move them up and down, scissors-style.

“This is my nub dance,” she said, swinging the nubs in various directions.

She jokingly bragged that she wouldn’t have to shave her legs anymore.

Other times she’d cry spontaneously and grieve the loss of her legs.

She did best when she was around other people, so she set about making plans. Her 33rd birthday was coming up on June 22. She wanted a Thanksgiving feast.

Her family and friends brought turkey, gravy, stuffing and other Thanksgiving food to HealthSouth. Vanessa bought two charm bracelets, each with a broken half of a heart that together said “Partners in Crime.” She gave one half to Norma and kept the other for herself.

Vanessa Marin is very close with her aunt Norma. The two share a charm bracelet that when put together spells out “Partners in Crime.”

On June 28, at Norma’s request, the Tucson Fire Department paramedics and firefighters who had responded to the scene April 19 came to HealthSouth so that she could thank them in person.

Norma, wearing a pink T-shirt and compression garments for her burns, wheeled herself into the room with a big smile on her face. In a low whisper, she told the Fire Department personnel that they were her heroes.

“You look much better than the last time we saw you. It’s good to see you like this,” paramedic Chris Clegg said. “This was one of those calls where you think it’s not going to end well.”

The crash scene was “horrific,” Tucson Fire Capt. Ray Dashiell said. But he said it was also clear, even at the scene, that Norma was fighting to live.

“I’m taking it day by day. There’s no point looking back. It’s the end of a chapter,” Norma said that day. “The key is to find that one thing that gets you out of bed. For me it’s my children, my husband, my family.”

Norma, center, wanted to meet the first responders whom she credits with helping to save her life. Here she talks with TFD Capt. Ray Dashiell, left, and Chris Clegg.

She was beginning to think about the future, and about when — or if — she’d be able to get prosthetic legs. The skin on her nubs was still thin, scabbed and often bled.

“Here at HealthSouth I am in my own community. I want to get more comfortable with my own reality,” Norma said.

Michael still hadn’t been back to work, and the family, at least for the immediate future, would exist on his income only.

Josslyn refused to play soccer again without her mother. The boys weren’t allowing anyone to potty train them. Since the crash, they had also refused to ride their new bikes. Life had been on hold.

Norma had also begun to think more about the night of the crash, trying to piece together what happened.

She had questions about Sergio Castro, the 25-year-old driver who hit her that night:

Was he facing any punishment?

Click here to read the next chapter, Blame. Click here to read the previous chapter, The Crash.