One morning in 1964, Fred Taylor, a seaman on the deck force, woke up and saw the sun rising in the wrong direction.

But that couldn’t be, so it must have meant that the USS Monticello, which was some 500 miles east of the Tokyo Bay at the time, had changed its course.

The seamen, who until then thought they were going back to the U.S., found out soon enough where they were headed, Taylor said. They were going to Vietnam.

“We were looking forward to going back and seeing our families,” he said. “But that’s what we were trained for.”

Taylor, the 70-year-old artist, didn’t have much of a choice in joining the military. His father was a former Marine and home life was often like boot camp, he said. “My father raised me to be in the military,” he said.

One day, when Taylor was still in high school, he came home to find his father waiting for him in the driveway. “Get in the car,” he said he was told. They headed for a recruiting office.

The first time he enlisted might not have been his choice, but when he came home to Tucson from his first two years, he said he got “fed up with civilian life.”

|

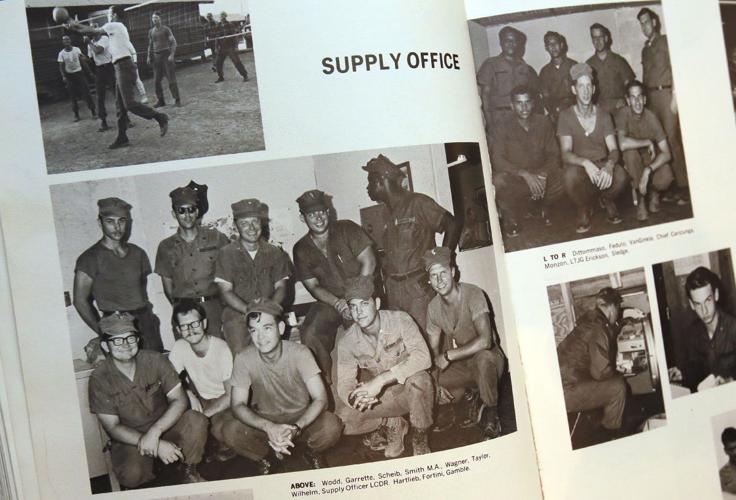

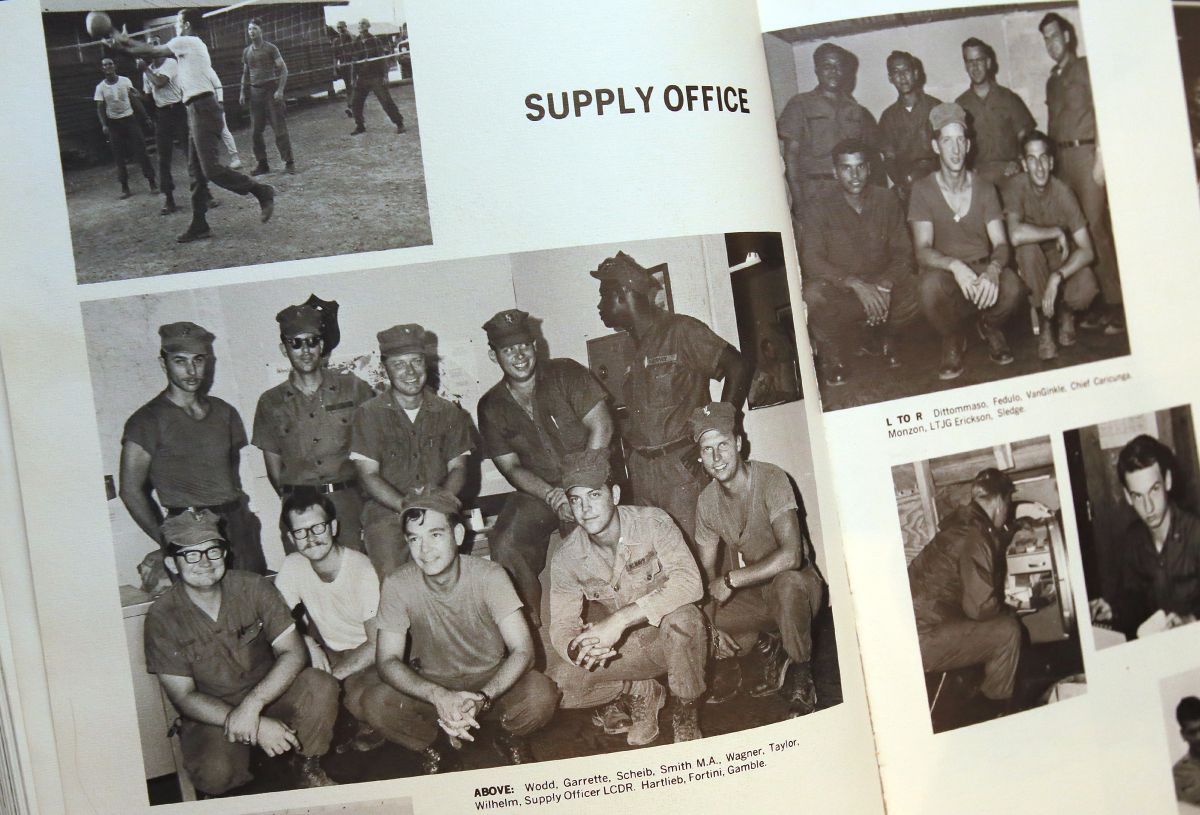

He went to Vietnam, again. This time, he was assigned to a mobile construction battalion, building and repairing roads, bridges and bunkers in Da Nang and Dong Ha.

Taylor said he quickly found that life on land was not the same as life on a Navy ship. “Nobody shoots at you in the middle of the night” on the ship, he said.

The attacks were frequent, especially in Dong Ha, the base camp of which was only about five miles south of the North Vietnamese boundary, he said. He remembered shots being fired as he got dressed to start the day. He and his hut mates jumped into holes they dug in the ground.

“I knew some friends of mine were dead,” he said.

In the aftermath, Taylor said the survivors were given some food, which included a biscuit, eggs made of egg powder and muddy water and a piece of spam.

He ate as he watched the bodies of his friends dragged from the hut, he said.

“I just stood there and watched,” he said. “I was numb, emotionally numb.”

War was not a good time to feel afraid, so he tucked the fear away to deal with later, he said. “VA says I got PTSD,” he said. “I call them demons.”

One of those demons was his 1997 diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, which the Veterans Affairs department acknowledged as being linked to exposure to Agent Orange, herbicides used by U.S. military during the Vietnam War.

Since then, he has been keeping busy nurturing his artistic side by painting, sculpting and writing poems. Not one corner of his Saddlebrooke home is deprived of art. There are stacks of multicolor paintings of buildings, skies, animals, trees, leaves, flowers and binders full of poems.

“That’s been a challenge trying to figure out where to put it all,” his wife, Faye, joked.

Taylor is not sure if creating art is meant to be therapeutic for him, but he said they are expressions of his subconscious.

In a recent poem, he wrote, in part, “A beast runs free it is me. And now not. Yet still lives in the souls of others.”