Anyone who has ever stared down a charging bull will understand why Louise Larocque Serpa adamantly and frequently uttered the adage that became her motto: “Never don’t pay attention.”

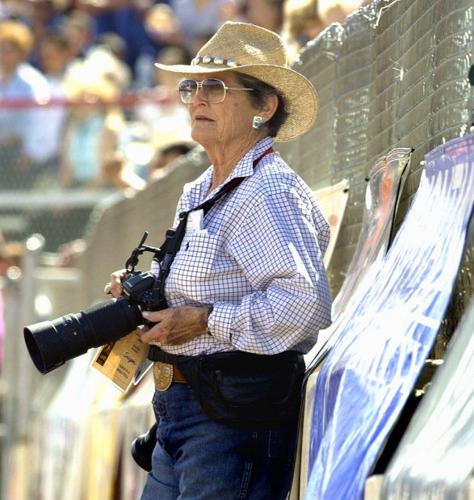

With her nose buried in the dirt and her eye to a camera, Serpa was the first woman permitted by the Rodeo Cowboys Association to venture inside the arena and shoot rodeo action. She photographed every Tucson rodeo from 1963 through 2011.

Serpa was born on Dec. 15, 1925, and grew up in New York society with a mother who was never satisfied with her lanky, unpolished daughter. As a teenager, she found happiness while spending a summer on a Wyoming dude ranch scrubbing toilets, waiting tables and wrangling cattle, all while falling in love with a handsome cowboy who loved to rodeo.

After the summer she returned to New York, earned a degree in music from prestigious Vassar College (she had a wonderful singing voice), married a Yale man — to her mother’s delight — and relinquished all hope of reuniting with the young cowboy and his life on the rodeo circuit.

When her marriage faltered, Serpa headed west again and met another cowboy, Gordon “Tex” Serpa. They married and settled on a sheep ranch in Ashland, Oregon, where Louise had two daughters, Lauren and Mia. That marriage also ended and she and her daughters moved to Tucson. A friend invited her to watch his children take part in a junior rodeo competition, and her interest in photographing rodeos was born.

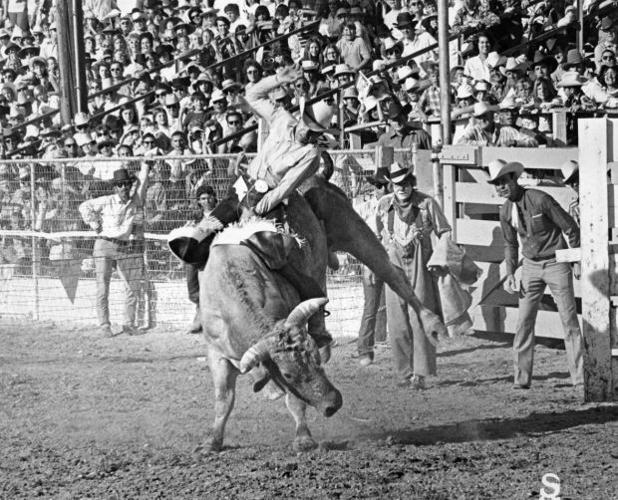

Using a drugstore camera, she began photographing youngsters as they bounced and bucked on small sheep and calves, then sold the pictures to proud parents for 75 cents each. At first she was relegated to shooting outside the rodeo arena, but in 1963 she earned her Rodeo Cowboys Association (RCA) card and became the first woman sanctioned to shoot inside the fenced arena grounds.

She traveled to almost every rodeo in Arizona, getting up close and personal with many a bucking horse and raging bull as she closed in to get the best shot. She survived one devastating encounter with a bull that caught up with her and tossed her in the air. Upon landing, the powerful animal shoved her into the ground and she suffered a broken sternum and ribs. She continued to shoot the rodeo before heading to the hospital, and was back in the arena the next day.

She photographed rodeos in New Mexico, Nevada and Canada, getting so near wagon races that her pictures appear as if she is standing right beside the stampeding horses.

Serpa expanded her expertise to photographing cutting shows and polo matches. She shot England’s prestigious Grand National Horse Race and the Dublin Horse Show in 1970, the first woman allowed to take pictures on the grounds of these centuries-old events. She also photographed the Sydney Royal Easter Show, a celebration of Australian culture, in 1975 and again is believed to be the first woman to do so.

In 1982, fashion photographer Bruce Weber saw some of her photographs while shooting an advertising spread in Tucson. He was so taken with the vividness of her pictures that he insisted she come to New York for an exhibition. He arranged a showing of her work, spread her name throughout the photography community and even used her as a model when, as Serpa said, “he needed old age and wrinkles.”

In 1994, Aperture Publishers produced a book of her photographs called “Rodeo.” She selected some of her best shots of cowboys hanging on to bucking horses and struggling to stay atop outraged bulls, as well as calf-roping events and those death-defying buckboard races.

She went to Africa and Australia to shoot wild animals with her camera. She traveled to China to record the stoic faces of Chinese peasants. In Morocco, she photographed the history and people of the region.

In 1999 Serpa was inducted into the National Cowgirl Hall of Fame, and in 2002 she received the Tad Lucas Award from the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, presented “to a woman who had done outstanding work in the sport of rodeo.” The Pima County Sports Hall of Fame honored her in 2005.

In 2006, she was grand marshal of the Tucson Rodeo Parade. She was the first grand marshal to ride a horse in the parade instead of sitting in a horse-drawn carriage, even though she once admitted, “I ride like a loose sack of grain.”

In 2008 she was diagnosed with cancer but even as she underwent chemotherapy treatments, lost her hair, and walked with a cane, she never stopped snapping pictures. She continued to photograph the Tucson Rodeo through 2011, when she finally let go of her camera and hung up her hat.

Serpa died on Jan. 5, 2012, at age 86. A wake was held at the Tucson Rodeo Grounds attended by men she had photographed years before, along with their sons and grandsons whom she had also photographed throughout her extensive career. All had experienced her charismatic presence as they bounded out of the chute and landed with a thud on the hard arena floor, only to hear her shutter clicking away.

She opened doors for women in photography as well as in rodeo. Her legacy hangs in galleries around the country and she has a legion of admirers, including the rodeo riders she captured with her ever-present camera.