In the spring of 1870, seven women came from St. Louis, Missouri, to Tucson to provide health and education to Arizonans. Their appearance in the territory was nothing short of miraculous.

From the Motherhouse of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet in St. Louis, sisters Monica Corrigan, Ambrosia Arnichaud, Hyacinth Blanc, Emerentia Bounefoy, Martha Peters, Euphrasia Suchet and Maximus Croisat traveled by train to San Francisco. From there, they took the steamer Arizona to San Diego. What lay before them was more than 400 miles of raw desert with danger lurking behind every creosote and prickly pear. Sister Maximus described it as “the abomination of desolation.”

Sister Monica kept a journal of their travels describing days of blistering heat and cold, arid nights. One night, they were invited to dine with a local ranchman. Enjoying their first hot meal in days, the sisters ate with several other ranchmen, but no other women graced the table. “Some of them proposed marriage to us,” wrote Sister Monica, “saying we would do better by accepting the offer than by going to Tucson, for we would all be massacred by the Indians. The simplicity and earnestness with which they spoke put indignation out of the question, as it was evident they meant no insult, but our good. ... For that afternoon, we had amusement enough.”

The sisters traveled by buckboard to the Colorado River, then boarded a raft to carry them into Arizona territory. The overcrowded ferry dipped dangerously close to spilling everyone. Two days from Tucson, soldiers joined the final leg through a narrow corridor at Picacho Peak, where Indian attacks were prevalent.

Within days of arriving in Tucson, the sisters opened St. Joseph’s Convent and Academy for Females. As Sister Monica wrote, “We had scarcely time to brush the dust off our habits before opening school.”

Within three years, the sisters were also operating a school at Mission San Xavier del Bac for Tohono O’odham students. In 1876, they started Sacred Heart School in Yuma and established St. Theresa’s School in Florence the next year. St. Joseph’s Hospital in Prescott started seeing patients in 1878, while St. John’s vocational school at Komatke on the Pima Reservation opened in 1901.

In 1876, the sisters completed work on a new provincial house and novitiate in the Foothills of the Tucson Mountains. Mother Irene Facemaz became provincial superior of Mount St. Joseph Novitiate.

Tucson-born Gabriella Martinez Otero walked through the doors of the adobe-built novitiate in 1877 to begin her training. She was one of six Tucson women who took their vows at Mount St. Joseph shortly after its inception. In 1880, she chose the name Sister Clara of the Blessed Sacrament and taught Spanish and art, as well as piano, harp, guitar and violin at St. Joseph’s Academy.

The novitiate was converted into an orphanage in 1886, housing an average of 30 children. In 1901, a violent windstorm damaged the orphanage beyond repair. After raising enough funds to rebuild, St. Joseph’s Orphanage opened in 1905 with room for 100 children.

Tucson Bishop J.B. Salpointe, who founded St. Mary’s Hospital in 1800, asked the sisters to manage the small, 12-bed infirmary. He sold it to them in 1882 with the provision it always be called St. Mary’s and be used as a hospital for the next 99 years.

At the time, the stone and adobe structure consisted of one floor for patients and a basement occupied by a kitchen, dining room, laundry and storage area. Mother Basil Morris ran the hospital with Sisters Mary John Noli, Julia Ford and St. Martin Dunn.

“There were only three doctors and two sisters besides myself working in the hospital,” Sister Mary John wrote. “Sister St. Martin worked with the doctors and the books, and Sister Julia and I were in charge of the 12-bed ward. It was hard work.”

In addition to their nursing duties, the four women washed and ironed all the linen used at the hospital, scrubbed floors, cooked and served food to the patients. One large wood stove heated water for patients’ baths as well as sterilizing surgical instruments. Coal oil lamps and candles were the only light available at night.

Mother Fidelia McMahon became head of St. Mary’s in 1893. Under her leadership, the hospital expanded into a modern health center with a surgical area that included a sterilization room, operating room, emergency room — and even a place to tie up ambulance horses. In 1905, electricity was put in. A sanatorium for tuberculosis patients was built next to the hospital in 1900.

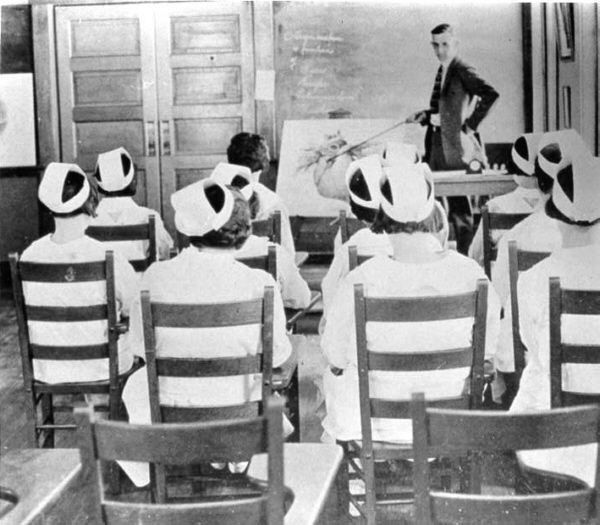

In 1914, Sister Fidelia initiated St. Mary’s School of Nursing, which gained accreditation in 1922.

A 1920 Tucson Citizen article lauded the achievements of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet. “No one single agency has done more for her civilization and progress, for her health and prosperity,” it said.